High C: A User’s Manual for Sports Fans to Better Understand Opera

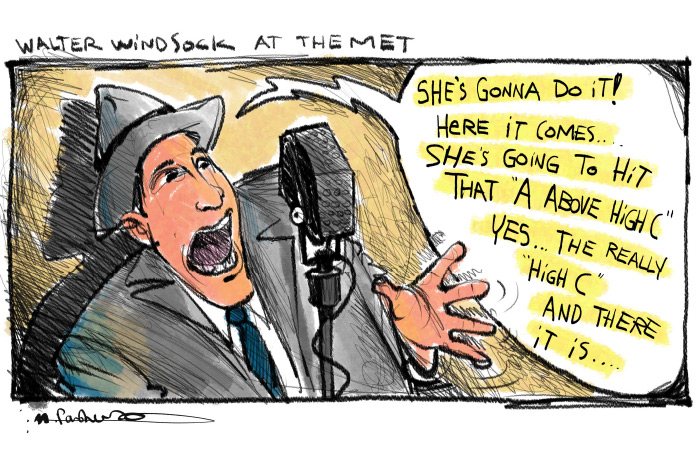

Last week, a singer named Audrey Luna hit the highest note ever sung in the 137-year history of the Metropolitan Opera House in Manhattan. It was an A above high C, sung in the middle of a new opera by Thomas Ades called The Exterminating Angel, and The New York Times published a story about it on the front page of the Arts Section this past Wednesday.

A photograph of Ms. Luna with her mouth open, supposedly singing this note, accompanied the story. And the feat was witnessed by all 3,000 well-dressed opera buffs attending. This was the American premiere of The Exterminating Angel, so the fact that this note was in the score was known only to the performers and perhaps a few others. The accomplishment was declared monumental and unprecedented by archivists from the Met. And it was reminiscent of the home run hit just four months ago by Aaron Judge at Safeco Field in Seattle that not only easily cleared 500 feet but broke the needle of the remote device measuring it. It may have been the longest ball hit in history.

For sports fans unfamiliar with the terminology of music and so unable to appreciate what “A above High C” actually is, an explanation is in order.

Notes are given letters as follows: The main note in roughly the center of the piano is a C. The next note higher is a D, then an E, an F, a G, and then, surprisingly, an A. The note B is even higher than the A. After the B, even higher yet, is the C above C, which is therefore “High C above C” to distinguish it. From there the letters start to go up for a second time to the next C above High C and then come up to High G above C and High A above C. These are, on the piano, the white notes. There are other notes colored black but they are not relevant to this explanation.

The note A above high C therefore is quite a bit up from the middle of the piano. The Times, and also the Met, do note that it is possible that B above high C (higher than A) might have been hit somewhere, sometime, just as Judge’s blast might have been exceeded in practice or in the minors. But that doesn’t count. The Met is the Met.

The Times, aided by archivists, reviewed the history of the highest note ever hit at the Met. This is similar to how, at baseball games, sportscasters can announce “this is only the second time in 32 years that a rookie has hit seven foul balls in a row.” With that, though, it is not archivists. It’s a set of headphones over their ears bringing them insta-statistics from a sports Google.

In 1908, a 39-year-old singer named Ellen Beach Yaw from Buffalo hit a G above high C during her only performance at the Met. A Times reviewer at the time wrote that she hit it a “flutelike Santos-Dumont” way, but then also said “She hit that high G as promised, but it is like Bat Masterson hitting a tomato can with a .44 at four paces.”

So one guesses she just took a momentary, but successful, shot at it.

It was also noted in the present story that Lily Pons, a French opera star, hit a high F in the mad scene from Lucia in 1931.

And that Silbyl Sanderson hit a G playing Massenet’s Manon at the Met around 1900 and another Frenchwoman Mado Robin was recorded hitting a B flat, but it was “shrill” and not at the Met.

Summing up here, you will note that the A sung by Luna is above either the F or G sung by Yaw, Pons and Sanderson, but below the shrill B flat, sung by Robin, but not at the Met.

So Robin’s feat is like in the minor league, or maybe something hit accidentally off the end of the bat.

Anyway.

As with all sporting events, the commentators interviewed both the singer, coloratura Audrey Luna, and the writer of the score, Thomas Ades, afterward in whatever passes for a postgame interview at the Met.

“The note, the range, the tessitura, is a metaphor for the ability to transcend these psychological and invisible boundaries that have grown up around them,” Ades said in the Times. He was referring to the plot of The Exterminating Angel, which is about very well dressed blue bloods at a fancy dinner party who seem to be unable to leave when it’s over. They go offstage, then come back. Ms. Luna sings this A at the very first moment of the opera. It is actually when she is offstage, about to stride on.

“It’s a moment of arrival,” Mr. Ades said. “It had to be on this note.” He means the note A.

On the other hand, Ms. Luna comes back later in the show and does it again to the guests. So that’s probably when they took the picture of her with her mouth open.

Also, it is not lost on critics that the well-dressed blue bloods at the opera are being sung to in the same way as the blue bloods at the party. Irony!

Ms. Luna, who grew up in Oregon, told interviewers she’s loved singing since she was in high school. “I liked the sensation it made in my bones, in my head, in my sinuses. It just gave me a high. It still gives me a high,” she said. She now lives in Hawaii.

Here in the Hamptons, many people still remember Boston Red Sox outfielder and Triple Crown winner Carl Yastrzemski hitting at the Lion’s Club ball field as a teenager for the Bridgehampton School. The games were jammed with people, all there to watch him hit the ball over the fence. But I don’t think he ever blasted one as long as Aaron Judge. (Or Mickey Mantle who, in 1960 supposedly hit one 643 feet in Detroit but the measurement was to how far it rolled.)

As for this current record, they say that records, even opera records, are made to be broken. We look forward to Ms. Luna’s attempting B over high C if she can get up the courage. Never before done. Ever.

And it can’t be “shrill.”