Montaukett Tribal Recognition Efforts Dealt a Setback

Last week, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo vetoed a bill, passed by both the New York State Assembly and Senate, that would have provided state recognition to the Montaukett Indians as a tribe. Having state recognition would not provide much help to the Montauketts—the Shinnecocks got such recognition in 1792 without getting much of anything because of it—but it can be a stepping stone to getting national recognition from the federal government. There, the Bureau of Indian Affairs stands ready to provide a greater degree of help to Indian tribes, which is what happened in the case of the Shinnecocks when they received recognition seven years ago.

The governor said he vetoed this state bill because, if signed into law, it would cause the state to bypass the process by which an Indian tribe gets state recognition. That process would have to include an investigation by the state to determine the tribe’s history and continuous existence over the centuries. And no such state process currently exists.

There is a catch-22 to of all this for the Montauketts. The process that the state proposes to set up in order to review the Montauketts’ request would be modeled after the federal process, which is laborious, long and very expensive. (The feds got the application for the Shinnecocks in 1973. It took nearly 30 years of investigation of historical records to decide that the Shinnecocks were a tribe.) But there is no investigation and you can’t have approval without the process. It goes around and around. Of course, the Montauketts are always free to go the federal route without the state recognition.

The road to federal recognition would be much more difficult for the Montauketts than for the Shinnecocks. The Shinnecocks were given a reservation to live on when the state recognized them way back when. And they can show a clear ongoing history for hundreds of years. That never happened for the Montauketts. In fact, without any reservation to call their own—they felt Montauk itself was their home—they lived among the white early settlers, having “sold” Montauk to a group of settlers known as the Proprietors. Because of this, many Montauketts died of the diseases the settlers brought. They had no immune defenses against these diseases. By the late 19th century, very few Montauketts remained.

In 1879, millionaire Arthur Benson of Brooklyn went to a Brooklyn auction house where Montauk was up for bid by the Proprietors. He purchased Montauk for $151,000, saying at the time he intended to use Montauk as a summer hunting and fishing retreat for himself and his friends. He told the remaining Indians there he would pay them $80 a year to get off his property. He told them the Montaukett tribe was being re-settled in Freetown and Oneida, New York, and in Wisconsin, and urged them to use some of their money to go there. Nearly all did. Fire destroyed the home of one Montaukett family that didn’t move at that time.

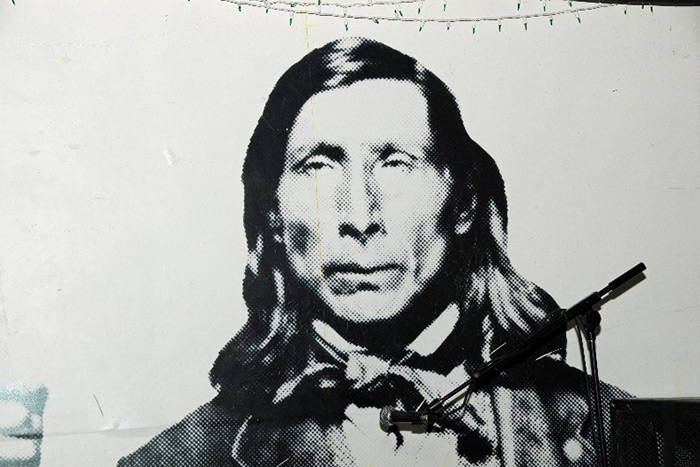

Perhaps the most famous of the Montaukett Indians was Stephen Talkhouse, who died at age 58 the year Benson bought Montauk. He was a famous “walker” and carried messages from Montauk to Amagansett and East Hampton and back for many years. He was a Civil War veteran and his grave is in Montauk.

Also famous was the chief of the Montauketts when the settlers first came in 1639. His name was Wyandanch, and he was not only Chief of the Montauketts for a number of years, but also of all the 13 Algonquin tribes on Long Island at the time the settlers came.

In 1910, a judge in a Riverhead court, in a real estate case involving Montauk and the Long Island Rail Road, declared that the Montauketts, having “lost their identity through intermarriage,” were “extinct.” Reports of this court case say that 24 Montauketts were present when the judge said this.

At the present time, Robert Pharaoh, a Montaukett living in Sag Harbor, is spearheading the drive for state and federal recognition. He could provide the State information about the tribe’s history but, so far, no one has asked.