63 Years Ago: The Hamptons Was Very Different When I First Arrived Here

I thought it might be of interest to tell you what the Hamptons was like in the 1950s. I arrived here in 1955. I was 15 years old at the time and I came here because my dad, a pharmacist, bought the drugstore in Montauk and, in doing so, brought the family out here from Millburn, New Jersey, the suburb where I grew up. I’d never been here before.

I finished high school, college and grad school away from the Hamptons. So for the first nine years, I knew it only in the summertime. I started Dan’s Papers in Montauk in 1960. Soon after that, I was here year round.

The long, four–mile stretch of Napeague Strip back then was barren of trees. You could see the ocean and the bay along it, almost the whole way as you came out for the summer. When you dropped down onto it from the higher ground at Amagansett, you knew right away Montauk was another place. There was a breeze, a dampness in the air, and the temperature was immediately five degrees cooler than in the Hamptons.

There were also dozens of giant billboards on the Napeague Stretch. All of the billboards were right at the start of the strip after the drop-down. They advertised fishing boats, restaurants, motels and bars. After the blizzard of them, it was barren of all human habitation all the way out to the Lobster Roll, which was there then and still there today.

Besides Napeague, long vistas could be seen in many places over long fields and ponds in the Hamptons. There were very few trees. You could see the ocean from almost anywhere.

Cars had tailfins in the 1950s. The cars were often painted in bright colors, sometimes in two tones, to accent the chrome. The cars had whitewall tires. Many belched smoke. There were no seatbelts. When you dropped down onto the strip, the AM radio stations in the car turned to static. There was no New York radio further on. (And no FM). All you got was New England.

We had black-and-white TV in Millburn, all the stations from 2 to 13. (There was no cable.) In the Hamptons, there were three channels, all from New England. There was a CBS TV on Channel 8 from Providence, Rhode Island, and two NBC stations, both from Connecticut, at Channel 3 and 12.

I have a strong memory of a TV commercial for Railroad Salvage, a lumberyard in a town in Connecticut. It was played over and over. We watched the local news in New England every day, which was really strange.

Gosman’s Dock in Montauk was a simple clam bar shack out at the jetties, a single building about 20 x 30. Mary and Bob ran it. Fishing boats docked at Gosman’s. There was a weighing station. Gosman’s was not the huge complex it later was to become.

On Sundays, all the stores in the Hamptons were closed for church. The towns were as quiet as a mouse.

Almost all of the motels in downtown Montauk, 30 of them, were built between 1950 and 1959. Montauk therefore was a brand-new, shiny motel resort town for fishermen and their families when we got there.

East Hampton’s Main Street was lined on both sides with giant elm trees that overarched the road and kept Main Street in shade all summer. (The long block coming down Woods Lane to the pond is sheltered by this sort of magnificent elm tree. The ones on Main Street died of Dutch elm disease in the 1980s. The new elms are disease resistant but much smaller.)

What is now London Jewelers in East Hampton was then the American Legion Hall. Large numbers of veterans were home from the wars on the East End. Every town had a Legion hall or VFW Hall.

In East Hampton, the police station was on the south side of Newtown Lane then, in the store that is today The Monogram Shop. There were two gas pumps on the sidewalk out front, where the police cars could gas up. And there was a lock-up in the back in an “evidence” room. I know. I spent an afternoon in it. Another story.

Across Newtown Lane was the post office, nearby to Sam’s. Across the way, where Cittanuova is now, was a Chinese restaurant called Lyons.

There was no IGA in Montauk. My mother shopped at Bohack’s, the only supermarket in East Hampton. It was located and in the same building that houses Citarella today.

The population of Montauk consisted of about 900 year–round people. Almost all were fishing boat captains and mates, bar owners, merchants and a few resort motel and restaurant owners and workers.

The Montauk Manor, high on the hill in Montauk, was a thriving hotel in the 1950s, on the order of a Catskills hotel. A shuttle bus took guests from the hotel to the Montauk Surf Club, which had an Olympic-size swimming pool and cabanas along a 300-foot boardwalk. The Surf Club is all washed away now.

The bar The Sloppy Tuna was, back then, a laundry for the linens from all the motels in 1955. Imagine that. An oceanfront commercial laundry (probably dumping the chemicals into the sea at the time.)

There were no curbs or sidewalks or street furniture in downtown Montauk then. You just pulled your car up and parked at an angle in front of the store you wanted to go into. Occasionally, people on horseback rode to town. They tied up to telephone poles.

There were no celebrities in Montauk or in the Hamptons back then other than from the Broadway crowd (Edward Albee, Marvin Hamlisch, Richard Adler). Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller had famously rented a cottage in Amagansett at Beach Hampton during the summers of 1951 and 1952. They were away from it all in the dunes.

The first year I was here, there were still steam engines hauling the Long Island Rail Road trains. They puffed smoke and chuffed through town. They had fancy Pullman parlor cars with porters.

The Long Island Expressway did not exist in 1955. They had begun building it through Queens at the time but that was all. To get to the Hamptons took four-and-a-half hours by car, not because of traffic but because the roads were two lanes and you went through almost every town along the way—Patchogue, Riverhead, Moriches, Eastport, Westhampton Beach, Quogue, etc. Patchogue had a big billboard when you came to it—PATCHOGUE: BIGGEST SHOPPING CENTER ON LONG ISLAND.

Smelly little duck farms backed right up to the Montauk Highway in many places in the Hamptons where the ponds came up to the road. They were in Eastport, Mecox, Flanders, etc. You could get out of your car and go over to the chicken wire fences enclosing them and throw bread crumbs at the ducks. You could also buy a freshly killed duck in the little retail shops there.

Bridgehampton was a farm town entirely surrounded by potato fields back then. There were six gas stations in town. Farm equipment could be repaired at any one of them. On warm summer days, you often saw black migrants from the South in filthy clothes sunning themselves on Main Street, talking to one another and drinking Thunderbird from inside paper bags they clutched. They looked happy and relaxed on their days off from harvesting the potato crop. Their temporary summer homes were primitive barracks on the farms. No electricity or running water. The migrants were brought up from places like North Carolina in yellow school busses in the spring and sent back down in the fall. The migrants, as a rule, did not go into white-owned stores or restaurants.

The potato and vegetable farmers, all white, would congregate every morning at the Candy Kitchen to have coffee and talk about the price of potatoes before going to work. Most of them were from Poland, others were descendants of first family settlers in the area.

Nobody spoke Spanish in the Hamptons then. There may have been a few Hispanic people but not many more than, say, folks from Norway.

The Ladies Village Improvement Society watered the flowers and gardens in downtown East Hampton. They were in charge of public order in the town, proper dress and seeing that all stores closed on Sunday. Members of the LVIS were descendants of the early settlers.

In the summer there were two big “do’s.” A fundraiser for the Hospital and a fundraiser for Guild Hall.

If 900 people lived year-round in Montauk, about 2,000 lived in Amagansett and East Hampton. Many worked for the wealthy WASP community that came out from New York City in the summertime to their mansions down at the beach.

When giant fish were caught offshore Montauk, word of it was radioed to shore and people would come down to the jetty to welcome the arriving boats home. I’ve seen sharks lashed to the side of a boat that were almost as big as the boat itself. My dad had a 58-pound striped bass stuffed and mounted over the pharmacy window in the back of the store. He’d caught that from his boat.

I had a rich uncle who entertained the idea of buying four vacant acres on Lily Pond Lane for $35,000 in the 1950s. He decided against it.

The value of homes was related directly to the price they could be rented for. Calculate the annual rent it brought in, multiply times 10 and that was the price it could be sold for. This was the rule almost everywhere back then, except in the estate section. Homes were for shelter only.

A group of perhaps 400 baymen and blue collar workers lived in small houses along several streets in Springs back then. They were called Bonackers and spoke English with a peculiar accent all their own. They clammed, surf-casted and tended lobster pots in the bays and harbors and pretty much kept to themselves. A few remain today. Many have sold their homes for a million dollars and moved on.

The Shinnecock Indian reservation to the west of downtown Southampton had signs at every road leading into it that read PRIVATE PROPERTY KEEP OUT. They kept to themselves.

Southampton Village enforced proper dress codes by village ordinance. Shorts had to cover between halfway from the hip to the knee. Shirts had to cover up breasts (to above the aureole—look it up). These laws remain on the books today but are not enforced.

Are you familiar with the big three-story white clapboard Chequit Inn on Shelter Island? There were two big hotels like that in the Hamptons, for the guests of the wealthy who came to visit. One was in East Hampton at the beach and was called The Sea Spray Inn. It stood where the Sea Spray cottages are today. The Inn burned down around 1980. The other was the Irving, which was located on Hill Street in Southampton. That burned down too, around 1985.

Sag Harbor was a run-down factory town in 1955. There was almost no active tourism. All the cute little whaling homes on Garden Street and elsewhere were mostly abandoned with broken windows, etc. Four factories in town employed blue-collar workers. The men wore hard hats and carried lunch pails. They made watchcases, gas caps and other devices. There was a noon whistle. There were two bars with sawdust on the floor, where the locals came to get drunk. They’d get into bar fights or get thrown out. The bars were the Black Buoy and the Sandbar.

There were many famous artists and writers living in hideaways in the woods of both East Hampton and Southampton. Willem de Kooning was here. Author John Steinbeck lived in Sag Harbor. All were here to be left alone, and they were.

Car dealerships were in the downtowns of Amagansett, East Hampton, Sag Harbor, Bridgehampton and Southampton.

The largest employer on Long Island back then was Grumman. They built fighter planes for the Navy and tested them very noisily over the East End from a facility in Calverton.

National affairs were far away from the Hamptons in those years. We listened or watched the news on TV for half an hour at the end of the day. During the day we lived our local lives.

There were no street numbers in 1955, except in a few places. There were also no area codes on the black rotary phones we had then. We had prefixes. So in Montauk, which a few years before we got there had phone numbers with just four digits, now had to have the town codes. They were MOntauk 8 (which is 668), EAst Hampton 4 (which is 324) and SAg Harbor 5 (which is 725), and so on. For calling people far away, you dialed the operator and had her connect you. There were charges for this long distance service to, for example, New York City. Area codes and zip codes came in around 1955 and 1965, respectively.

General Dwight Eisenhower was President of the United States.

The East Hampton Airport Terminal consisted of a farmer’s old chicken coop pushed up against a World War I barracks building at the side of the runway.

You could drive to any beach and park at any location in the Hamptons, except at somebody’s property, without a beach sticker.

There were no wineries.

There was a traffic light in the center of town in Southampton and another in the center of town in East Hampton. That was it.

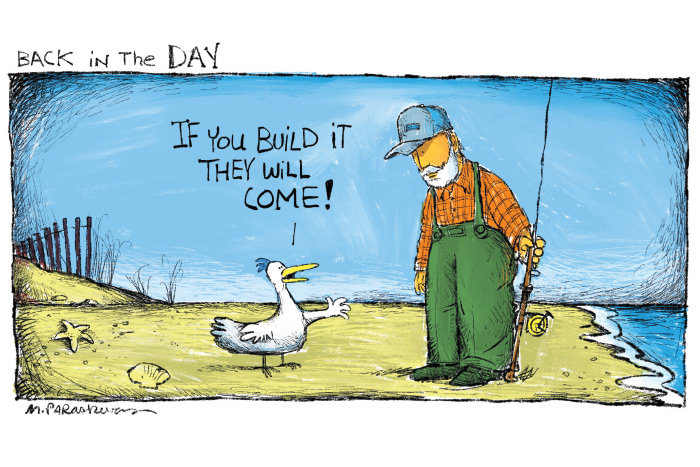

On Sundays, a hound dog could fall asleep on the white line in the center of Main Street and go undisturbed in almost any town in the Hamptons.