Montauk 1919: Attempting the First Nonstop Flight Across the Atlantic

Most people think the busy village of downtown Montauk was established all at once in 1926, when millionaire Carl Fisher bought the Montauk peninsula and bulldozed a grid of roads into an empty 100-acre field. Fisher built churches, stores, a bathing club and that odd-looking six-story skyscraper that faces out onto the Plaza.

Fisher’s development of Montauk went into receivership after the Crash of ’29. But the bare bones of what he built remained and have developed into the thriving village you see today when you drive in from the west.

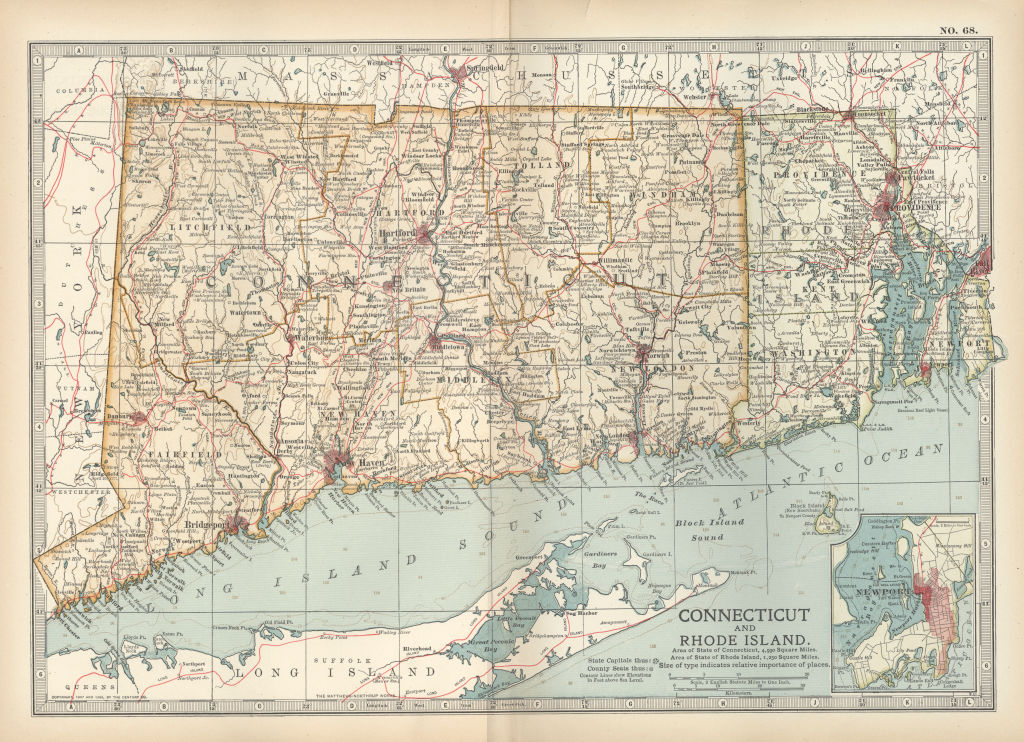

It turns out, however, that a huge Navy complex of nearly 30 buildings was constructed where downtown is today, just 10 years before Fisher came. The complex took up 32 acres of what is now downtown. From it, biplanes and dirigibles were flown along the coastline of Montauk on surveillance missions. The year was 1917, and America had joined the French and English to fight Germany in the trenches of Europe.

The war ended in November 1918. But the American Navy didn’t decommission the naval base in Montauk until August 2, 1919. And, as they always did, they just moved out and left everything as it was. But six years later, when Fisher first laid eyes on the place, he decided the buildings were taking up space for his planned resort city. So he had the complex bulldozed. All that remains today is an unused launching ramp into the pond next to the downtown soccer field.

The Montauk Library has several photographs of the Naval Air Station at Montauk taken from the air. They were taken from a biplane in 1918. You can see the pond and the ocean. On the shore of the pond, next to a supply dock, huge hangars housed the dirigibles and biplanes. Behind them were the barracks buildings, warehouses and officer’s quarters.

There was no runway. The biplane seaplanes took off skimming along the waters of the pond. The dirigibles were launched from an open field next to the pond. The vast size of this complex suggests there might have been as many as a thousand naval officers there.

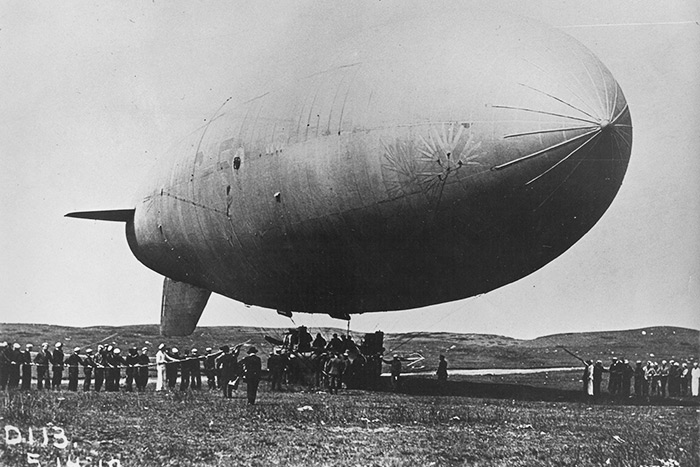

Their was an incident in 1919, which began on May 14, three months before the base was decommissioned. Four dirigible pilots—Lt. J. Campbell, Lt. J. B. Lawrence, Lt. Charles Little and Lt. Commander E. W. Coll—were given permission from their superiors to try to fly one of the Navy dirigibles across the Atlantic Ocean to England, nonstop. No aircraft had ever done that. The four fliers that day in May, with members of the press in attendance, launched the 196-foot-long dirigible C-5 over Fort Pond and flew it out to sea.

They planned to stop at a dirigible field at St. John, Newfoundland, where they would get gasoline, hydrogen and supplies. From there they’d go across to Europe. Heading for Newfoundland, they became temporarily lost in a thunderstorm near St. Pierre Island, Canada. They found their way but then got lost a second time in a storm over Newfoundland when their navigation equipment malfunctioned. Using voice radio, they contacted the U.S. Navy Cruiser Chicago in port in St. John, and thus made their way to a tie-down spot near there.

The engines were opened to be serviced, and the crew departed to get supplies of food and water (which were now very low), but then the storm worsened. Lt. Little climbed into the gondola and pulled the lever that would cause a rope to deflate the gasbag. The rope broke, and Lt. Little leaped back to the ground just in time before the storm ripped the dirigible free and carried it out to sea, never to be seen again. Little suffered a sprained ankle.

As you may know, the first person to fly across the Atlantic alone (he won the $25,000 prize offered up by New York hotel owner Ray Orteig) was Charles Lindbergh. He took off on May 20, 1927 from Roosevelt Field, at the western end of Long Island. But that is another story.

***

Montauk may have been the first airfield of consequence in the Hamptons. But there were many more—some just private grass strips—and what follows is a survey of some of them that I know.

In those early days, before 1920, fliers delivered mail and flew from place to place in biplanes at speeds of about 80 miles an hour, navigating by looking down for monuments and buildings that coincided with these things located on maps they had in the cockpit.

On Scuttlehole Road in Bridgehampton, there is a barn with huge letters spelling out BREEZE HILL in white shingles on its red roof. There was a grass strip at Breeze Hill. The big sign, clearly visible from the air, told you that. The federal government decreed that people paint names of places on the roofs like that. They did so all over the United States. Some still remain.

Flier (and later billionaire) Howard Hughes flew into Breeze Hill. He also landed at another grass strip just to the west of Hayground Road, northeast of the tracks in Bridgehampton. A small barn where planes were housed is still there. Hughes also came out by seaplane to visit a girlfriend whose parents had a house on the banks of Georgica Pond. I’ve met people who, as boys and girls, remember seeing his yellow seaplane circling around the pond before landing. He’d have a few kids climb aboard and take them on a free half-hour ride over the pond before walking up the dock to visit his friend.

The East Hampton Airport was founded in 1936 with Works Projects Administration (WPA) government funds. The first terminal was a former World War I army barracks that a farmer towed over. An expansion occurred when another farmer towed over a chicken coop to be attached to it.

What is now Gabreski Airport in Westhampton was built by the Army in 1943 during the Second World War for fighter planes to defend Long Island from possible German attacks. After the war, it became a commercial airport, but during the Korean Conflict and the Vietnam War, the Air Force briefly took it over again. Today, Suffolk County owns the airport as a general aviation facility and shares the property with the legendary Air National Guard’s 106th Rescue Wing, which, like an airborne fire department, is scrambled to rescue mariners in distress at sea by rappelling rescuers down ropes from helicopters.

In the 1950s, a secret Army guided-missile base was established in the woods near Gabreski, where BOMARC missiles were put in tubes sunk into the ground. These were each 40 feet long. There were about a dozen of them. The empty underground “silos” remain there today.

Farmers often built small planes from kits in those years, particularly after the Lindbergh flight. The farmers would fly off to visit friends and neighbors who had airstrips. Nothing was regulated. I know of a former grass airstrip off James Lane in East Hampton (in the field where Author’s Night takes place), and another just south of the General Store in Sagaponack, where a farmer had cleared a path through a cornfield.

During World War II, Grumman aircraft built a private airport in Calverton where they could test their fighter planes. They continued with it for many years. In 1990, Grumman sold the land to the Town of Riverhead, as I recall, for $1, and today it is an industrial park—with a runway.

Montauk Airport opened in 1958, a single runway parallel to the beach with a shack at the end. It’s still there and in use today.