How Dan Saved the Montauk Lighthouse from Getting Dynamited

When I was a little boy I had an elderly uncle who’d gather us, his young nephews, around at family events and tell us stories about his time as a soldier in World War I. He was a short, heavyset fellow with bushy white hair and a thick neck. To us little kids, of course, he was a great man and we hung on every word of the stories he told. My favorite was how he saved New Jersey from the Germans.

“I was assigned to guard the Parsippany Reservoir,” he said. “It was just me and the reservoir, night and day. I had a gun. One night, I saw the Germans coming. There were seven of them. They were creeping single file along on the curving edge of the reservoir, helmets on, rifles at the ready. I raised my gun. I only had one bullet. What should I do?

“Using all my strength, I bent the gun barrel into a curve. Then I fired. The bullet went through each German, continued on entirely around the reservoir and then came back to land, kerplunk, right into my gun. If there were more Germans, I could fire again. But there weren’t any more. And that’s how I saved the reservoir from the Germans.”

We cheered. Yay!

“And it wasn’t so easy to do all this,” he continued. “Earlier that year, when I enlisted, I showed up for basic training and got in this line with the other recruits. When I got to the front, they took out a tape and measured my neck all the way around. Then they turned and gave me my uniform, all folded up. Big neck people got big uniforms. I put mine on. The sleeves hung down almost to the floor. My slacks hung over my shoes. And yet, I saved the reservoir. And I got a medal.”

He declined to show us this medal.

A generation later, when my four kids were little, I’d gather them around me and tell them the story about how I saved the Montauk Lighthouse. It’s a long, complicated story, but I’d like to tell it now. It is also a true story.

In 1960, the first edition of what became Dan’s Papers had a drawing of the Montauk Lighthouse under the logo. The lighthouse was to the East End what, at that time, the Empire State Building was to New York City. It was our monument—graceful, tall, stunning and high on its hill almost entirely framed by the sea. No one would ever think of hurting the Montauk Lighthouse. Or so I thought.

Dan’s Papers in those years was just a summer paper. I’d come home from college and publish it once a week June through August, then go back to school. I wrote the history of the lighthouse in one issue. It had been built in 1796, its light guiding in ships and keeping them from harm. But once, a mix-up had caused a tremendous crash.

The year was 1858 and, further to the west, a lighthouse had just been built at Ponquogue Point in Hampton Bays. Montauk’s flashing light sequence was reassigned to the newer lighthouse. A new and different flashing sequence was now assigned to Montauk. The word went out. But it had not yet reached the captain of the John Milton, a 1,440-ton schooner that had left South America bringing several tons of freight to its home port at New Bedford, Massachusetts.

Strong winds and rough seas slowed the schooner down, and the captain, seeing what he thought was the light sequence at Montauk, turned north to give himself a wide berth before reaching home. Instead, he sailed the John Milton full speed into the beach at Montauk’s Ditch Plains. He and his 32-man crew died. All were buried at the South End Burial Ground in East Hampton.

In 1967, the seventh year I had been publishing the paper—still only in the summertime—I put a call in to the United States Coast Guard at Montauk Lighthouse to learn how badly the cliff in front had eroded during the prior winter. I had been doing this every year. The Coast Guard measured the distance from the front of the lighthouse to the edge of the cliff and kept a log of it. When it was built it was 350 feet from the edge. But now, every year more and more of the cliff eroded away.

You have to know that in those years nobody particularly cared about saving historic places. Everything back then was about tearing down the old to make way for the new. It had been only two years, for example, since the owners of the magnificent Pennsylvania Railroad Station in Manhattan—which was as grand as Grand Central—had torn it down to make way for a taller building. Nobody cared.

“So what’s the number this year?” I asked the coastguardsman.

“This year’s measurement is 65 feet 7 inches.”

“That’s more loss than you’ve ever recorded in one year since I’ve been calling you.”

“I guess.”

“Six years ago it was 77 feet. Let me do the math. If this keeps up, the lighthouse will fall into the sea within twenty five years.”

“Well, it won’t do that,” the coastguardsman said. “We’ve got new orders. The chiefs intend to tear the lighthouse down and put up a steel tower twice as high as the lighthouse 400 feet inland. The light up there will be operated by remote control. That solves the problem.”

I think the coastguardsman expected me to cheer. Instead, I was horrified. I told him that. We quickly ended the call.

At the time I was on the phone with this call, a friend named Ron Ziel from Hampton Bays was in my office on a social call. I told him, actually screamed at him, what I had just learned.

He had further information. “The Coast Guard is decommissioning lighthouses all up and down the East Coast,” he said. “It’s a cost-saving measure. It’s expensive to run a lighthouse.”

“They can’t do that here. This is the Montauk Lighthouse.”

“They tore down the lighthouse at Shinnecock,” Ron said.

“There is no lighthouse in Shinnecock.”

“Not any more. They dynamited it to the ground in 1948. As a matter fact, there’s a framed photograph of it halfway down at the barbershop in Hampton Bays where I get my haircut. It was taken just as the dynamite exploded. The bottom is tilting one way, the top the other. There is a huge white puff of smoke. Bricks are flying everywhere.”

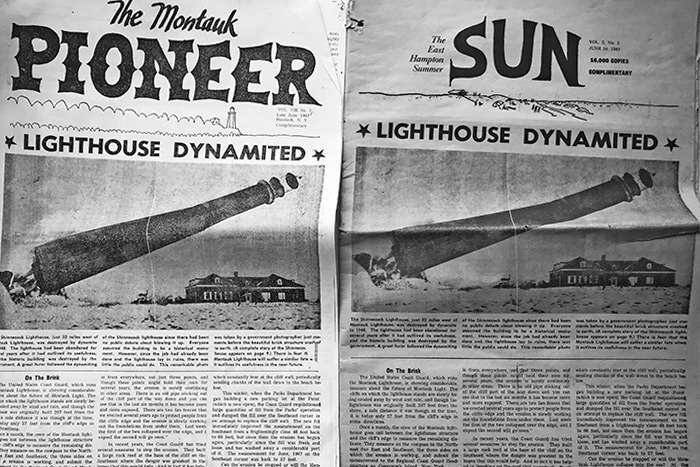

At that moment I knew what the cover story of the first issue of the summer was going to be. It went out that Saturday in an issue of 14,000 copies. At the top of the page under the logo was a two-word headline: LIGHTHOUSE DYNAMITED. Under it was the photograph of the Shinnecock Lighthouse from the barbershop in Hampton Bays. Below that was the apology for showing a different lighthouse, but that was what was in store for the Montauk Lighthouse if the Coast Guard had its way.

The town was electrified by this story. The following week, I announced the formation of the Save the Montauk Lighthouse Committee. Everyone was invited to come out to the Montauk Lighthouse parking lot at 9 p.m. on a Saturday night, carrying lit torches, lanterns, flashlights, searchlights, flaming cheerleader batons or flares and holding them high where the Coast Guard could see we meant business. This Light-In, as I called it, would last precisely one half-hour. We’d fire a cannon to start it, then fire it again to end it.

According to The New York Times, which covered the event, 1,500 people showed up that particular Saturday night. Fire trucks were up there. There were Scottish bagpipe players, the Bay Shore Marching Band, the Huntington Militia and their cannon, numerous government officials including the New York State Minority Leader Perry B. Duryea Jr. (who lived in Montauk), all of whom spoke over a PA system about the need to save this historic site.

The Coast Guard’s reply to this was to re-affirm their opinion that the lighthouse was coming down and there would be something taller, more efficient and less costly there.

It was then that I learned that this lighthouse was the first one in New York State, and it was ordered built by President George Washington himself. They could not do this!

We held a second demonstration at the lighthouse. This time, the local police reported the crowd at 3,000 people. And this time, lights appeared in all the windows of the lighthouse lighted by the coastguardsmen inside. It was an emotional half hour. We had friends.

During this period, I was contacted by many people who expressed interest and support. One contact came as a letter from the President of the Security National Bank, one of the major banks on Long Island. He asked what he could do. I then noticed that the logo for the bank, right there on the stationery, was the Montauk Lighthouse. I wrote back he could join the Save the Montauk Lighthouse Committee, of which I was chairman.

After this second demonstration, the Commander of the Coast Guard District wrote an order withdrawing their plan to tear down the lighthouse. They would take care of it, put a new coat of paint on it, maintain it as the monument it was.

Then a little old lady named Giorgina Reed appeared at my office. She had brought with her a slender book she had written, called How to Hold Up a Bank. There was still the problem of the earth sliding down the cliff face in a storm causing the lighthouse to fall. She had a solution to this. It was right there in this book, which she opened to show me.

“It’s how the Japanese stabilize a cliff face,” she told me. “You create terracing using wooden planks as risers and rich soil as treads. You plant strong, hollow reeds in the dirt. It takes root. It soaks up the rain, and no more dirt slides down.”

She and her husband, Donald, had bought a waterfront property in Rocky Point facing Long Island Sound. Shortly after they bought it, a big storm tore out 10 feet of the cliff face there and much of their lawn. She wouldn’t have it. She built this natural retaining wall, and it was doing the job. She believed it would hold up at the lighthouse, too.

“Would the Coast Guard let me build this on their property?” she asked me. I didn’t see why not.

The next Sunday, Giorgina came out to the lighthouse in a station wagon with her husband and five or six volunteers. They brought with them wood planks, pails, beach grass and loam, and they started digging and planting. They did this every Sunday for an entire year, all year around, every single weekend, and then did it a second year and a third.

The erosion stopped where they worked. After the sixth year, the Army Corps of Engineers placed huge boulders around the tip of Long Island down at the waterline to absorb the heavy surf and serve as a foundation for Giorgina Reed’s project above. And after 10 years the job was complete. The cliff face at the lighthouse is now bright green with foliage and grass. And it is still 67 feet from the lighthouse.

In 1981, the Coast Guard invited both Giorgina Reed and me to attend a luncheon under a tent at the Coast Guard Headquarters on Governor’s Island in our honor. It was a beautiful sunny day. The Commander spoke. We were both presented with a framed commendation. Mine was in appreciation for what I did. Hers was for the accomplishment that she achieved. Driving home together, the two of us agreed this was a classy thing that the Coast Guard did.

No, I had not saved the lighthouse. I had kept the Coast Guard from destroying it. Georgina and her volunteers are the ones who saved the lighthouse.

In 1987, a huge celebration was held on the lighthouse lawn facing the parking lot to honor Giorgina Reed. Officials spoke. The Coast Guard Band played. And a long letter from President Ronald Reagan was read over the PA system, honoring the unbelievable effort put out by a determined little old lady named Giorgina Reed. Many people wept. Giorgina Reed could not be there. She was then 80 years old and ill, home in Rocky Point.

What a thing she did.