'Sticky Fingers' Offers a Backstage Pass to Jann Wenner's Life

When Jann Wenner and his wife Jane first followed Paul Simon and Lorne Michaels to the Hamptons in 1977, they rented in East Hampton, staying in an “eighteenth-century shack on Further Lane, next to designer Ralph Lauren,” author Joe Hagan writes in Sticky Fingers, his 2017 biography of the Rolling Stone magazine founder.

Wenner would move his East End retreat from East Hampton to Montauk after a lifetime of changes — including kicking a massive cocaine habit, coming out as gay in 1995 and eventually marrying a man — but The End was not so much associated with the rich and famous back in 1977. As Andy Warhol explained in his diary at the time (and Hagan recounts in Sticky Fingers), “If he had rented [in] Montauk he could have had something great, but I guess he and his wife Jane just wanted something ‘adorable.’”

In those days, as Sticky Fingers tells it, Wenner was about being the toast of New York and becoming a publisher who would eclipse the likes of Hugh Hefner and William Randolph Hearst. He wanted to be with, and be seen with, celebrities and business giants. The Hamptons was just part of that, and Montauk might have been a wonderful spot for artists like Warhol, who frequently hosted Mick Jagger and The Rolling Stones there, but it was not the place where you have Ralph Lauren as a neighbor — at least not yet. (The designer has since settled in Montauk.)

In East Hampton, “You’d pick up the newspapers on Sunday, go read the Times, and you’d see a picture of Ralph on the beach,” Wenner told Hagan, “and you’d go to the beach and there’d be Ralph on the beach.” He made a point of impressing his famous neighbor, Lauren, with a silver Ferrari he bought from songwriter Jimmy Webb. He had John Belushi out to stay when Warhol visited, but the comedian was just one of many who would pass through Wenner’s doors.

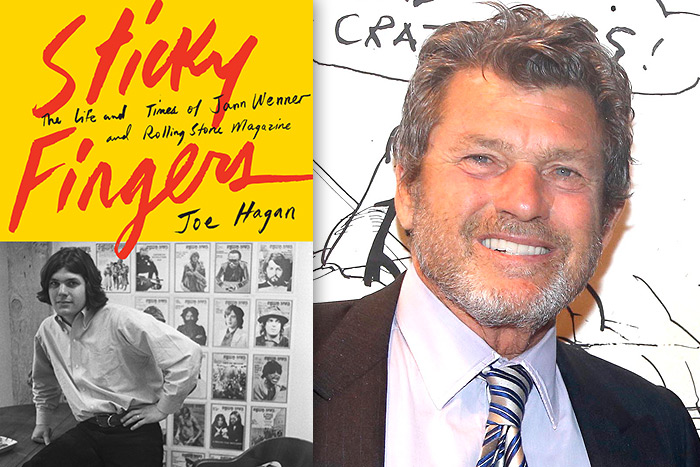

Published last fall, Hagan’s Sticky Fingers: The Life and Times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone Magazine offers an in-depth look at this storied Hamptonite, from childhood to the creation of his revolutionary magazine, all the way up to his most recent exploits and business dealings. Wenner commissioned Hagan to pen the book and agreed to give the writer complete editorial freedom.

The author received unfettered access to Wenner, his papers and anyone he deemed worthy of interviewing. He had final say over the end product because Wenner didn’t want Sticky Fingers to be a vanity project. At least Wenner thought he didn’t.

Hagan completed the book after dozens of hours interviewing his subject and speaking to more than 240 sources over four years. But shortly after reading the 547-page manuscript last September, Wenner turned on Hagan. True to his word, and likely an ironclad contract, he did not try stopping the publication, but Wenner and Hagan no longer speak. In an interview with The New York Times, Wenner called the book “deeply flawed and tawdry.”

Those who have read Sticky Fingers shouldn’t be overly surprised by the reaction. Assuming Hagan’s assessment is true, Wenner is no fan of ceding control — and that temperament, no matter how difficult for some to bear, has served him well over more than five decades in publishing.

Sticky Fingers indeed presents him as an imperfect and almost sociopathic man driven toward success at any cost. But if Wenner would take a step back, he might see that it also paints him as an innovator and survivor — someone who’s been unwilling to compromise where it counts in a rarified life full of opportunities to do just that.

So he screwed over a lot of people along the way? Where would Rolling Stone, the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame and a dozen of his other achievements be if he hadn’t?

Wenner helped define the culture of rock—the culture in general — through the pages of his vaunted publication, and Sticky Fingers tells the deliciously entertaining story of how he did it.

The book offers a taste of Wenner living the high life — and the high life — as well as his many legendary pals and associates, including some stories about the publisher’s life and famous friends in the Hamptons during an era before the volume was irrevocably turned down.