Lindeberg & Lily Pond

Although architectural scholars Peter Pennoyer and Anne Walker showcase 20 of the most important houses designed and decorated by Harrie T. Lindeberg, a little known leading light of “the American Country House Era” (1900-1930), this celebratory review notes only four of his commissions.

Each exemplifies Lindeberg’s best work during the 1906-1914 period when he worked with his partner Lewis Colt Albro, before going solo. The four houses are all on Lily Pond Lane in East Hampton.

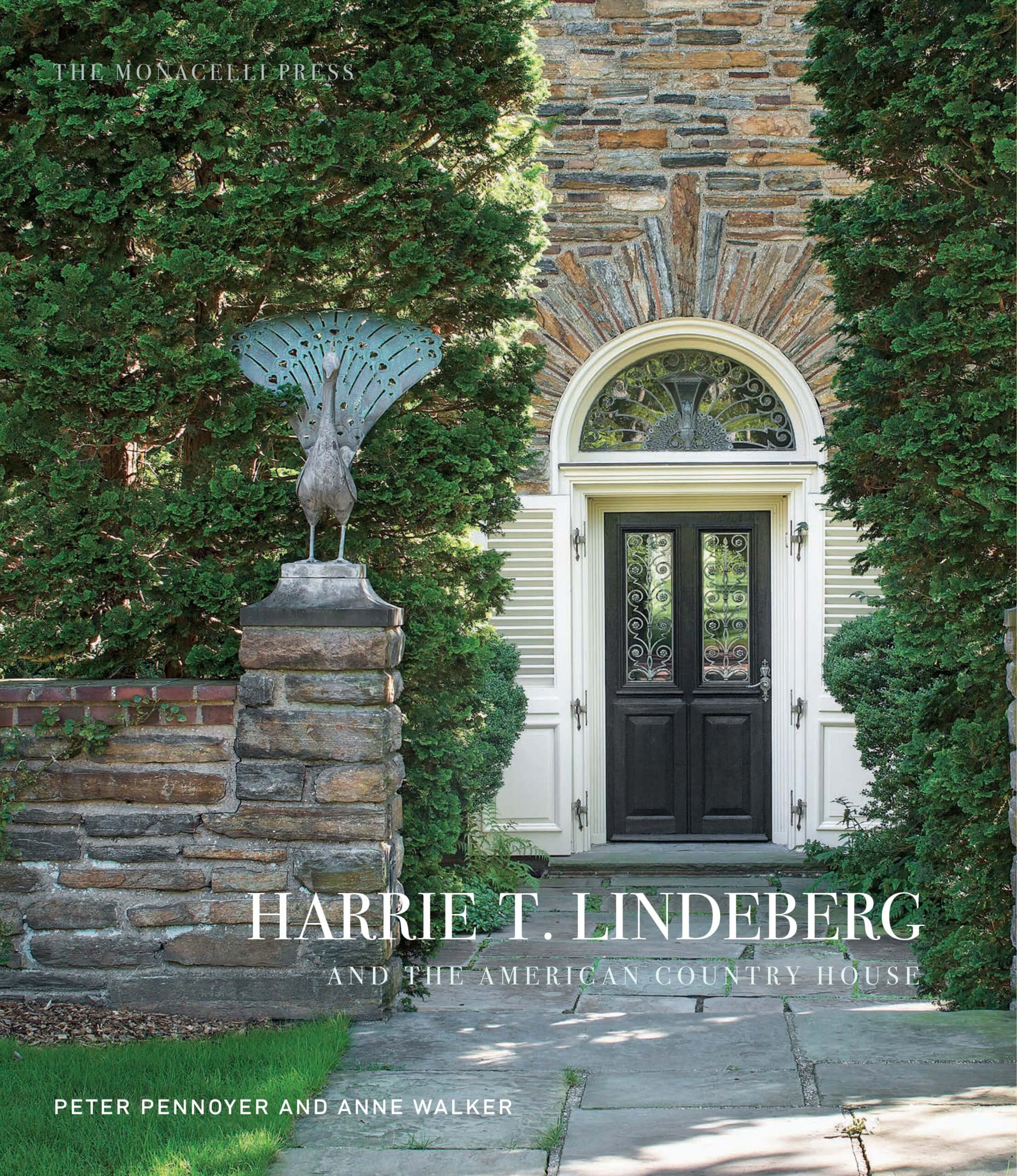

A handsome book, with beautiful photography and a persuasive, accessibly informative introduction, the book should prompt lovers of the elegantly simple, subtly innovative, and historically charming to set out on a spring morning to see for themselves (landscapes permitting) these four stunning signature residences. Readers can then appreciate why the authors revisited Lindeberg’s achievements and made a strong case for his legacy.

In a brief foreword to the book, noted architectural critic Robert A.M. Stern suggests that Lindeberg, like Stanford White, with whom Lindeberg worked at the prominent turn-of-the-20th-Century firm McKim, Mead & White, was a “traditionalist” who drew on diverse sources “which he did his best to conceal.”

It’s not clear what this comment means, but Stern does declare that Lindeberg’s “genius” was to synthesize the various sources of his inspiration into “an identifiable personal style” that is as “relaxed” as it is classically disciplined.

Perhaps he means that Lindeberg’s “borrowings” were so subtle that he did not lend himself to be defined by any one style, and thus he did not invite emulation. Lindeberg was not shy, however, about his opposition to modernism and urban industrial design.

Pennoyer and Walker make a more likely suggestion for Lindeberg’s relative obscurity, namely poor timing. Greatly admired in the early decades of the 20th Century after the extension in 1896 of the Long Island Railroad to Montauk ensured a growing wealthy suburban population coming east, Lindeberg suffered a diminution of clients with The Great Depression.

Then, the authors suggest, the “the onslaught of modernism” overshadowed his picturesque accomplishments. By the 1940s, few architectural historians were interested in his work or monographs.

Thanks to Pennoyer and Walker, who found additional sources for Lindeberg’s aesthetic principles and practices and took advantage of new developments in color photography, Lindeberg is now seen in context with his contemporaries.

American born, but with Swedish ancestry, he utilized his roots as a design inspiration, serving up a unique concept of “cottage” design, blending “vernacular” and “classical,” and appropriating Tudor, Norman, Georgian, and Colonial styles, along with elements resonant of the English Arts and Crafts movement and Beaux-Arts.

His houses, showcasing “simplicity in design,” were meant to be comfortable examples of “domestic living,” homes with “personality,” not cold baronial estates. As he once said, and his houses clearly show, good taste “is the essence of restraint.”

The authors quote a client who once asked how his style might be defined. The answer? “A Lindeberg house.”

And here are the houses, at the heart of a “burgeoning enclave” of shingle style cottages, with their distinctively Lindeberg touches: steeply pitched roofs (the Swedish influence), overhanging eaves, long unbroken rooflines, sand-colored facades, rhythmic groupings of windows, houses organically embedded in their surroundings.

1906: The Edward T. Cockcroft House (Little Burlees), a warm, buff-colored home, later occupied by an aunt of Jackie Kennedy Onassis and faithfully rebuilt after a fire in 2008. It features expansive loggias and pergolas and telltale Lindeberg rounded shingles at roof corners that give the impression of English thatch.

1908: The Dr. Frederick Kellogg Hollister House, with its “low-hipped roof,” vine-covered pergolas and porches, and floor plan showing the front door opening directly into the living room.

1913: The John F. Erdmann House (Coxwould), which emphasizes Lindeberg’s “uncanny ability to create facades that were at once balanced, asymmetrical, and inviting.” A neat tidbit is that Dr. Erdmann, a surgeon, once operated on President Grover Cleveland’s mouth when they were on a yacht on Long Island Sound.

1914: The Clarence F. Alcott house, more English and romantic in spirit than the others, shows a great sweep of a low flared roof and hooded “eyebrow” dormers.

This is a rich, lush volume featuring Harrie T. Lindeberg houses across the country, though local readers are sure to take special pride in what’s on Lily Pond Lane.