An Unexpected Life

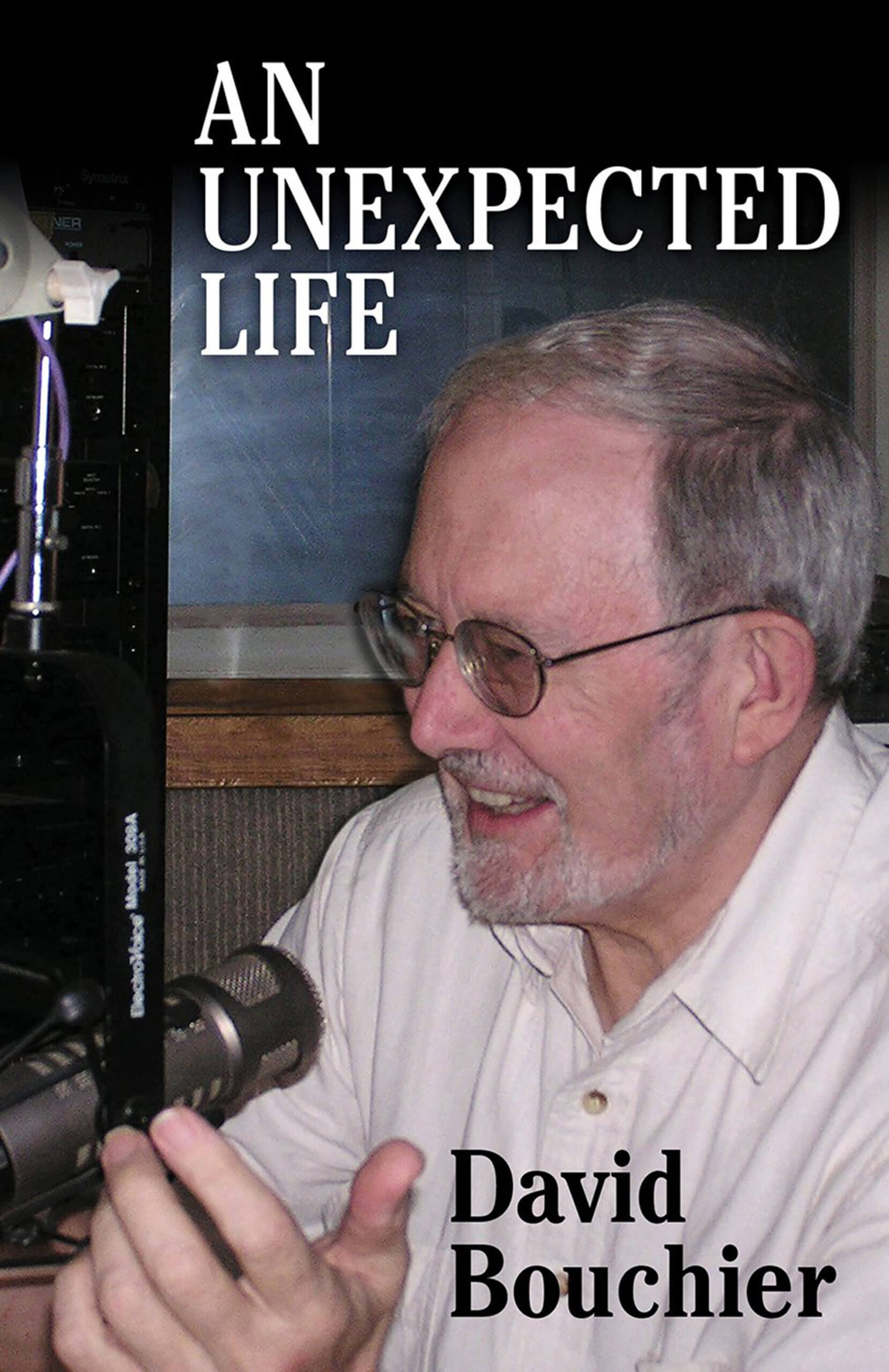

Measured, mild-mannered David Bouchier’s memoir, An Unexpected Life, is unexpected in what it says about this witty British transplant whose ironic cultural commentaries have for years been a staple on NPR, until he retired recently from full-time radio work, writing, and teaching to spend more time doing the same things.

Like many of the author’s radio essays, the memoir begins matter-of-factly, but soon understatement and whimsical self-deprecation punctuate the simply structured sentences. And then we realize that we have been gently guided from an apparent pedestrian remark to a significant observation on some of the more absurd and misguided ways of the world in which the author has moved in the last 79 years.

David Bouchier is a master of the unassuming familiar essay that moves subtly and unexpectedly from describing everyday experiences to serious reflection about what he notes, with humor and regret, as some of the more unfortunate trends of modern life.

He presents himself as a charming, fallible observer and a mistaken, sometimes foolish but willing participant. He bears witness; he does not scold. As for the accuracy of his recollections, he quotes Mark Twain in an epigraph: “I can remember everything that happened, whether it happened or not.”

Who would have thought that this laid-back, careful wordsmith had been mad for motorcycles, dropped out of school at 16, courted the counterculture as an anarchistic, bearded hippie who enjoyed radical ideas, pubs, and sex. He married three times (his last, at last, a loving 30-plus year relationship with an American artist and teacher).

Some adventures were fraught with danger, as he pursued exotic travel, but what carried him through, and what still buoys him, is a passion for reading. An only child, he was “left alone a great deal of the time, a freedom I enjoyed enormously and abused shamelessly.”

Reading bred in him a skeptical intelligence and encouraged an undiminished curiosity about how others lived, even as he shunned some of the wayward world’s offerings, such as drugs and hard rock.

Some horrors he could not avoid, such as being drafted into the National Service “despite extremely poor vision, multiple health problems, and a bad attitude.”

He eventually went back to school (“an overage undergraduate”) and got a Ph.D., with an eye on becoming a research-oriented sociologist. But he “wanted to be a 19th-Century social philosopher, not a 20th-Century academic sociologist,” and he fell in love with teaching.

Bouchier took advantage of openings where he could, moving back and forth as an adjunct teacher between his home base at the University of Essex, where he had been a student, and the U.S. (starting and continuing intermittently at Stony Brook). He also crossed the country selling British books to American libraries. And he also wrote several of his own (after flirting a bit with becoming a psychotherapist).

He still loves an audience, but some of his best teaching resides implicitly in his essays. He writes: “We owe an awful lot to the civilizations of ancient Greece and Rome. The Greeks invented the alphabetical script, without which the New York Times and the National Enquirer could not exist. They invented philosophy, which allows us to ask awkward questions about democracy, and they invented musical theatre, which is a pretty good metaphor of democracy.”

In particular, Bouchier likes exploring the 18th and 19th-Century roots of 20th and 21st-Century political and societal phenomena and giving them admiring voice.

After 32 years teaching college-age students, however, he gave it up because “their culture had passed me by.” David Bouchier is a man of words not images. Indeed, his lifelong habit of keeping a diary seems quaint to a generation that twitters and tweets. But the habit continues.

“I comfort myself with the thought that, if I keep writing, I will have the thrill of being an antiquarian, the satisfaction of keeping alive a dying art, and the sheer bloody-minded pleasure of not giving up,” Bouchier wrote. He would persuade us that the older we get, the more we should appreciate Somerset Maugham’s suggestion that “the best frame of mind in which to conduct a life is a kind of humorous resignation.”

In An Unexpected Life, Bouchier says he’s written a book that is “as truthful as memory allows and as kindness dictates,” the complete truth being, as he quotes a modern philosopher, possible only “anonymously” or “posthumously.” The reader is fortunate that David Bouchier is here and now.