Climbing Mount Misery: World's Tallest Mountain Is Unconquered No More

March 27, 2018

Charlotte, Scott and I arrived in Sag Harbor at 4 p.m. yesterday and spent our last night in civilization at Baron’s Cove. This morning, we met with the seven East Hampton Bonackers we hired as sherpas for the climb up Mount Misery. All appeared quite hardy and ready, although nervous.

There are many legends about what might be up top there above the clouds. But nobody has ever succeeded in climbing Mount Misery, and only a few of those who’ve tried have come back down. Our guide asked to be paid for the five-day expedition—three days up and one down—in advance. We had no choice but to oblige them.

March 28, 2018

At dawn, we agreed we should do a practice run. Instead of Mount Misery, we sent the Bonackers ahead to set up a nylon ultra-light tent at the top of Turkey Hill, a nearby peak that has frequently been climbed. It was from Turkey Hill during the War of 1812 that the militia rained cannonballs down on British Redcoats who were trying, unsuccessfully, to make a landing at Long Wharf.

After a hearty breakfast, we left Baron’s Cove at 8 a.m. and set up a sea level supply base at the corner of Rysam and Bay Streets, in front of Billy Joel’s house. After an arduous but short climb using cleats, grappling hooks, pickaxes and nylon climbing ropes, we arrived at the stone monument atop Turkey Hill.

Our skintight nylon Himalayan climbing tights under goose down mountaineering suits kept us warm in the 20° weather, and the Bonackers had a warm soup dinner ready in the tent when we arrived.

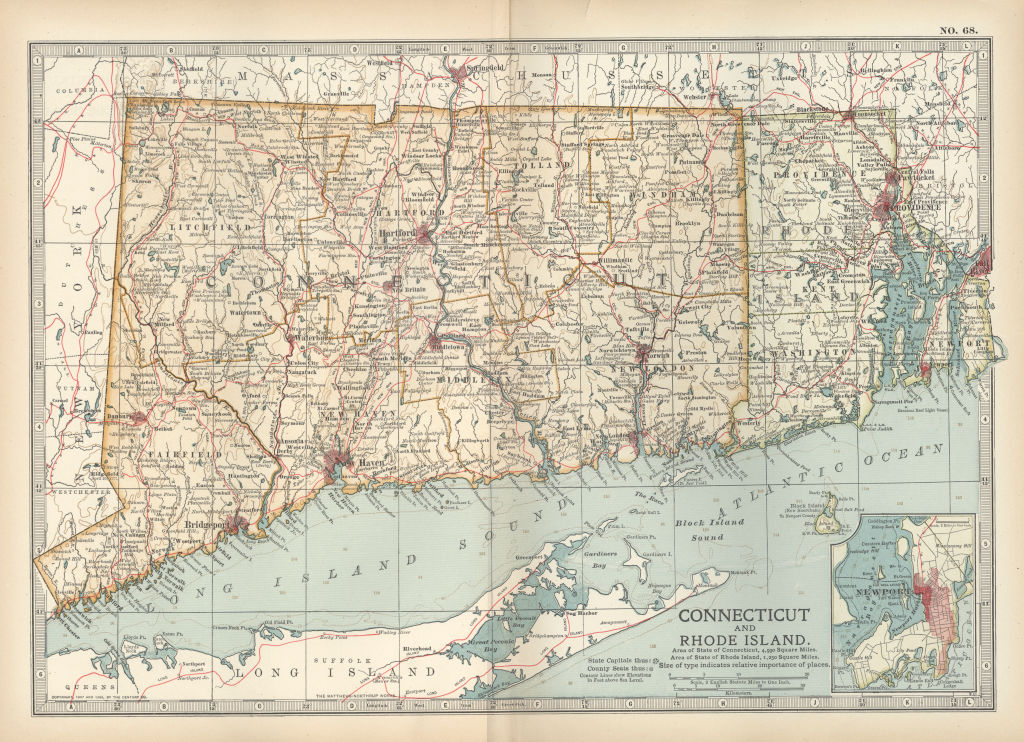

Prominent Sag Harbor residents came by in the evening for tea to wish us luck, including Billy Joel, Ted Conklin and Pat Malloy, and we thanked them for their company. After they left, we got the maps out and plotted our route up Mount Misery again. We debated starting the climb from the Sagg Road side as had been done before by others, but again wound up deciding to take the route up the steep south face from Collingswood.

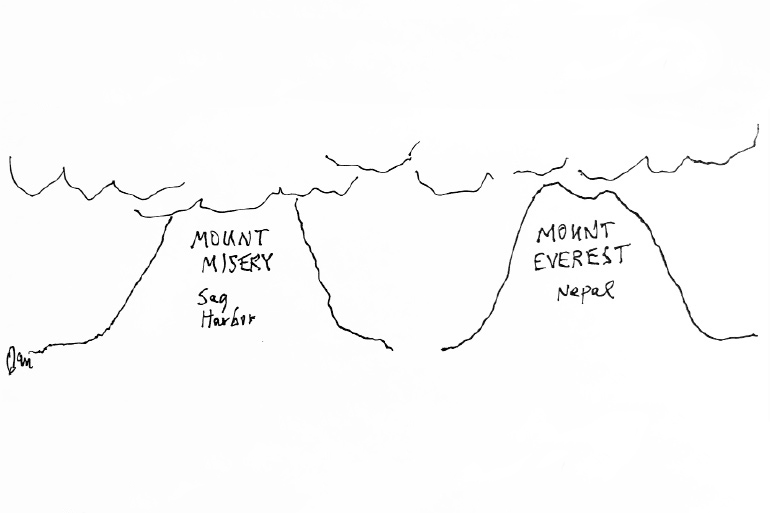

Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay tried it that way before their Mt. Everest climb in 1953. Although they failed at Mount Misery like everyone else from either side, they did say they felt this was the only way up. If it was good enough for them, it’s good enough for us. At least they got down safe, a feat in itself.

The three of us slept well in the tent on High Street at Turkey Hill, and the Bonackers slept on the grass nearby. They are used to that.

March 29

Dawn breaks and we are off. We’re excited and eager, the three of us in front, and the Bonackers single file behind. We got up to Survivors Camp after 14 hard hours of climbing. It’s named that for those who gave up the next morning and were just glad to get back after failing, but surviving. As expected, the wind is howling. The temperature is -10°.

March 30

We tackled the famous Backbreak Face beneath the clouds, setting our grappling hooks and ropes in a screeching rain. Arriving at Woozy Ledge safe, Scott argued we should turn back, we had gone far enough. But Charlotte and I are adamant that we continue, so we will. Only a few have gotten to Woozy Ledge.

We saw an old radio locked in the ice. Looked like the one Tenzing used in 1952, which he lost. We left it. Brickman, one of the Bonackers, felt sick after eating some of the Cliff Shot energy gels we break open for food. He’d had one of the peanut butter ones.

March 31

We climbed into the underside of the clouds. Visibility five feet. Temperature -20°. Many granite outcroppings and boulders appear suddenly. And a near disaster. Charlotte, although using chalk on her hands, lost her grip and tumbled, only surviving because of the line that ties us together.

Arrive at the abandoned remnants of High Base Camp at 9 p.m. We are down to three Bonackers now. One gave up, two died on the trail. No choice. We left them. Tomorrow we climb to where no man has been before, through the clouds. Hopefully, we reach the top in the evening, but we don’t really know. Nobody knows.

If it’s an extra one day further up, that would be fine, but two more days further up, we will run out of supplies. In our goose down sleeping bags, we hear the coyotes howl this night. How they could live up here is beyond me.

April 1

Is Mount Misery is the tallest mountain in the world? We hope to have the answer by nightfall. Midday the sun peeks through the clouds for a moment, and it is searing. Thank God for polarized goggles. But the clouds close it up. A temporary treat and a good sign.

April 2

Last night, no peak. A disappointment. We set the tent on the incline. The clouds remain tight. Almost no visibility. How much further, we do not know. But we’re going to continue. We are going to go on half rations.

April 3

Scott has the shakes and is running a fever. We ice-pick up and up. We are now out of radio and telephone range. But the clouds still hide us into the night. A seven-foot white bear prowls and snarls around our tent at four in the morning. An ice storm rattles our nylon tent. We are going to rest tomorrow—we have to. The following day we hope will be the final thrust to the top.

April 4

Two of the three remaining Bonackers carry Scott on a litter, higher and higher. He is talking rapidly, voice shaky, sometimes delirious. The altimeter gauge shows we’re at the height of Mr. Everest. Mount Misery really is the tallest peak in the world. But we remain in the clouds.

April 5

It’s happened. The clouds brighten. We are up now at 29,302 feet and suddenly, we are in bright sunshine. And there it is, the peak, the very top just another hundred yards ahead of us. Scott stirs, then climbs down from the stretcher, energized by the heat of the sun in spite of the -55° temperature. It’s amazing. We are here.

We scamper along now on all fours, cheering and howling to the very peak. The peak is just off-center of this island above the clouds, 300 yards in diameter. The remaining two Bonackers take pictures of us three happily holding the Stars and Stripes at the very top. We set the camera down on photo delay and have it take pictures of all five of us.

We stay here staring at the horizon of billowing clouds below in every direction for two hours—flashes of lightning go off—until the sun sets over what must be Southampton. We sing patriotic songs, then eat the final bits of rations and slide into sleeping bags in our tent.

The wind screeches, the full moon shines through the nylon rising from the horizon. Tomorrow we head back down.

April 6

We’re moving down swiftly into the billowing clouds, exhausted, hungry but exhilarated. And we have news. The Stars and Stripes is staked out at the top, frozen in place. Someday, others will see it there. People say that the Old Whalers’ Church on Union Street in Sag Harbor is the tallest building on Long Island. But they are wrong. We did not see her steeple punching through up there. Our guess is that a years-ago catastrophe ripped off the top in the swirling clouds. We arrive for a solid rest at Survivor Camp.

April 7

Back down. Celebration time.