Favorite: The Best Dan’s Papers Hoax Ever and What Happened Next

People seem to enjoy my occasional hoax.

I write of a rich South African man with a mansion in the Hamptons who flies in a herd of lions to deal with the deer problem here once and for all. Stay in your homes all day next Friday. I write of a monster who lives at the bottom of Long Pond in Bridgehampton and comes out to terrorize the community once every 100 years. Last time was 100 years ago.

So we’re due. In this week’s issue, I write of a new company that will remove any hacks that break into your computer. Sirens and flashing lights go off on the ceiling. Grab the mallet, run out front and hit the Buddhist gong with it. They are hoaxes, but they are both believable and preposterous. The preposterous is the giveaway.

My personal favorite hoax took place in 1992. That January, I wrote of a sporting event that would take place in March at the Lighthouse. It was based on the slogan that says that “The End Is Montauk, and the Next Stop Is Portugal.” There’s truth to this.

The sporting event was called “Flight to Portugal.” Every year, the teenagers in Montauk drive out to the lighthouse in their old cars, where a wooden ramp has been constructed at the edge of the cliff. The teenagers, one at a time, drive up the ramp as fast as they can and arch out over the cliff and into the ocean. The one that gets the farthest out wins the first prize, a six-pack of beer and a crown of laurel leaves.

The preposterousness here was the cars crashing into the sea, killing people. Duh.

But after this story, something totally unexpected happened.

One month after it was published, I received a letter from the Portuguese National Tourist Office on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. The director, a Mr. Carlos Lamiaros, wrote that he wanted to offer a first prize to the winner. The winner would receive a one-week vacation in Portugal, including round-trip airfare on TAP (the national airlines), accommodations in fine hotels, seven breakfasts and three dinners. Was this man pulling my leg? The letter had raised lettering and looked authentic. So, tucking it into my shoulder bag, I took a Jitney to New York and met with Mr. Lamieros. The offer was real.

“You know people don’t actually drive off the cliff,” I told him.

He smiled. “I think whatever you do would be good publicity for Portugal,” he said.

So here’s what I did—I really did these things. I decided that we should postpone the event to August and a time when the water was warmer. I wrote that in the next issue, thus piling on more hoax. The Montauk Chamber of Commerce helped me pick a date in August where it would help tourism the most.

I went to a meeting of the Montauk Boatman’s Association and asked if they would give a $100 bond to the youngest entrant. They voted yes.

I called the Montauk Historical Society based at the lighthouse and got approval for the event for Saturday, August 23. Because of the value of this prize, I felt we had to accurately measure the farthest one out to be sure we picked the right winner.

For this, I went to see Grumman Aerospace, the largest employer on Long Island, at their headquarters in Medford. They made the vehicle that walked on the moon. They made Navy jets and surveillance planes. Grumman was a big deal. I had to go through security and get a badge to get in.

I wanted them to send up one of their surveillance planes to circle around, measure the distances and pick the winner. They said they had something better. And they took me to see it in a laboratory. It was the size of a tractor-trailer truck.

“This is a GPS,” they told me. I had no idea what that was. This was before GPS. They explained it. They’d made it for the military. They’d try to arrange to haul it out to the Lighthouse that day.

A caterer agreed to set up a barbecue pit on the Lighthouse lawn and sell burgers, fried chicken, hot dogs and drinks.

I arranged for the Jim Turner Band. And I called WLNG and asked them to send out a news wagon. I also sent press releases out to all the New York media.

The event would consist of people THROWING gliders off the edge of the cliff. They could not be powered by either gasoline or electricity. They could be powered by rubber bands, throwing, and the wind. I put ads in the paper explaining Flight to Portugal and asking for entries. The next week, I got a letter from the Montauk Surfing Association objecting to the event, saying that among other things it would result in trash in the ocean.

To fight that perfectly good objection, I went to see Henry Uihlein at his boat rental operation at his store in Montauk Harbor. He agreed to have a speedboat offshore, picking up the entries for the duration. We also got the 54-foot Point Wells packet boat, the largest Coast Guard vessel based at Montauk at that time. Manned by the men in their white parade uniforms, it would be on hand if any rescue situations came up, but the Coast Guard also told me they might have to go off to assist in any other rescue situation nearby that afternoon that might come up. I said I understood.

I created a program for the event, which included an aerial view of the grounds showing the runway, pits, food, crowd, band and a “media area.” I had a big spectator area. “Bring a blanket or folding chair to sit on,” it said in the program. “No umbrellas.” The funds collected from a $10 admission charge would go to the Montauk Lighthouse Erosion Control program. There was an entry form in the program, and also in the paper.

There were the rules—and now a new rule that your entry had to float at least five minutes so Henry in his speedboat could pick it up. To enter, send in the filled-out form with a $10 application fee and we’d send you back written confirmation of a time slot for your launch. The first launch would be at 10:30 a.m., the last launch would be whenever. We’d have a pit area where entrants could lay out their planes and get them ready. There would be a launch runway. A roped-off section was for media photographers.

Saturday came as a wonderful, bright sunny day with a brisk wind. And so, beginning at 10:30 a.m., the band played, the smell of BBQ filled the air, the TV reporters narrated and the crowd cheered. Coverage was provided by ABC News, Channel 12, WINS, WLNG and various magazines and newspapers.

Police and fire trucks were on hand. And offshore—surprise!—dozens of sport fishing boats out there dropped anchor in the rolling seas of the rip to enjoy the show. And they were soon joined by what turned out to be a sailboat race that decided to have itself held that day.

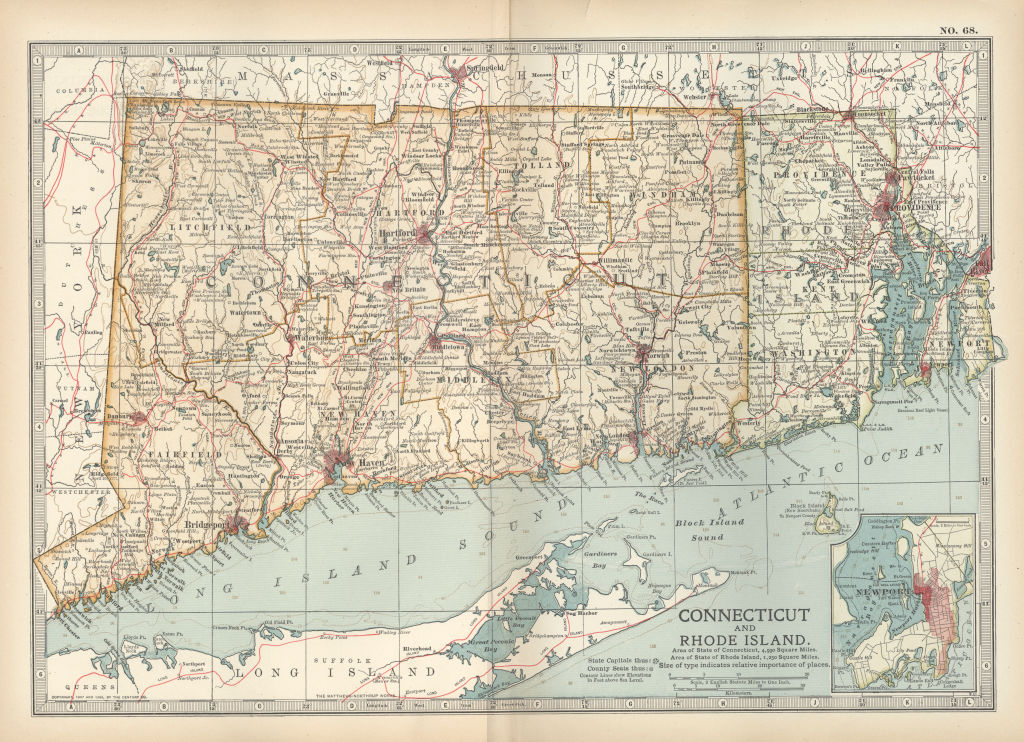

Entries were as small as handheld or as large as planes with 12-foot wingspans. Many were quite colorful. Black, yellow and red dominated in that pit area—quite a show for the spectators. Some had PORTUGAL written on the side, others had some random number or flag. One entrant had 14 propellers, seven on each wing. The entrants came from as far away as Connecticut and New Jersey.

I got on the loudspeaker, asked the band to finish their number, and when they did called the next entrant, said a little about their glider and where the entrant was from, told them to step forward with their glider, get ready for everything on the runway for the five minutes, and when it was time to count down from 10 to launch, go for it. I waved to Grumman up in the tower. They waved back. Some entrants spent the five minutes checking the events out. One woman sat cross-legged by hers and offered a prayer, palms up. Then it was time.

“Three, two one, GO!”

With that, the entrant went running down the runway holding his contraption aloft, and just before reaching the edge of the cliff, heaved it out. Some entries floated beautifully out over the ocean and then gracefully landed in the swells to await pick-up.

One entry headed out, went straight up, looped around and went backwards toward Amagansett. Another rode the air seemingly endlessly, then came to a halt and nosedived down into a great splash. Then there was the entry called TEAM EGG, a giant white egg on three bicycle wheels. Five people pushed it and it rumbled down the runway and fell over the cliff. What fun! (Henry Uihlein and his speedboat handled the pick-up in the ocean, surfers provided it down on the rocks. So the Egg got returned.)

In the end, we had 55 entries. They came from all over the northeast—New Jersey, Connecticut, Westchester, Long Island. (We had to shorten the launch time to three minutes—including the launch from Dick Cavett, who told me when I asked that he’d learned about this from the woman who ran the Chamber of Commerce.) And about 500 people came out to watch, including Carlos Lamiaros, who, besides the grand prize, also bore five pieces of Portuguese pottery that, he said, would be for second prize.

Other prizes came from Gurney’s Inn, Alize Cognac, Orangina and SolBar PF, the PABA-free sunscreen. Pro-Body Exercise Studio set up an exercise mat near the BBQ stand, the Montauk Yacht Club and the James Lane Café at the Hedges Inn in East Hampton offered up dinner for two.

When it all ended, we had to wait for Grumman to figure things out and bring the name of the winner to the microphone.

The first prize was won by Steve Wolff of Port Jefferson Station, a letter and plaque personally presented by Mr. Lamiaros, who then, unplanned, offered up more prizes for Mr. Wolff.

This included a beautiful piece of Portuguese porcelain from Ilhavo (value $600), and a three-liter bottle of vintage Taylor Fladgate Port from the Douro region of Portugal.

Wolff then spoke and told how he had made his entry—six-feet wingspan with propellers front and back, with the first triggering the second when it was spent. Ingenious indeed. Wolf then said he didn’t know what to do with the prize, since his wife was terrified of airplanes. So I don’t know what became of that.

Things that went wrong: The Point Wells did have to go off after one hour at the event. There was a sailboat foundering in six-foot seas near Block Island. Grumman failed to show up with their GPS, stating as an excuse that it was too tall to fit under railroad trestles, and so instead they arrived with a team of surveyors who set up equipment on the cliff edge and also up the 60-foot flight of stairs to the top of the World War II Navy tower in front of the Lighthouse. Men and the equipment could be seen from below, peering out the machine gunner’s window.

Also, the WLNG newswagon, a British double-decker bus, wouldn’t start at the end of the day and so had to remain where it was overnight—where, as it turned out, it was spray painted by vandals.

Ah, but all in all it was such a wonderful event.

The Flight to Portugal ended at 3 p.m. and then everybody involved in making it happen retired to Kahuna, a bar downtown, for refreshment.

This hoax and its subsequent event won First Prize in my heart.