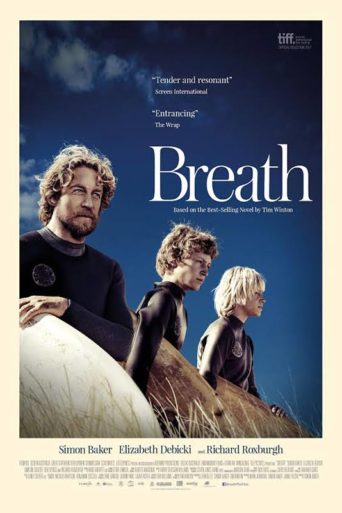

Danny Peary Talks To 'Breath' Director and Star Simon Baker

It’s not unusual that after seeing a good movie I read the source novel, because I am often intrigued by the choices made during the adaptation process. But it is unusual that after reading the book, I immediately see the film a second time. That was my experience after seeing Breath, Australian actor-director Simon Baker’s adaptation of Australian novelist Tim Winton’s international bestseller of the same name. I couldn’t let the story go. It’s a mesmerizing film coscripted by Winton, Baker, and Gerard Lee (Top of the Lake) that on the surface seems simple and innocent but is actually complex and often dark and will keep you wondering about the characters and their risky choices long after the film ends. And that’s why I recommend it. See how it affects you when it opens this Friday at the Angelika in New York City and on June 8 in Los Angeles and select cities before a national rollout. It has already opened in Australia to positive reviews.

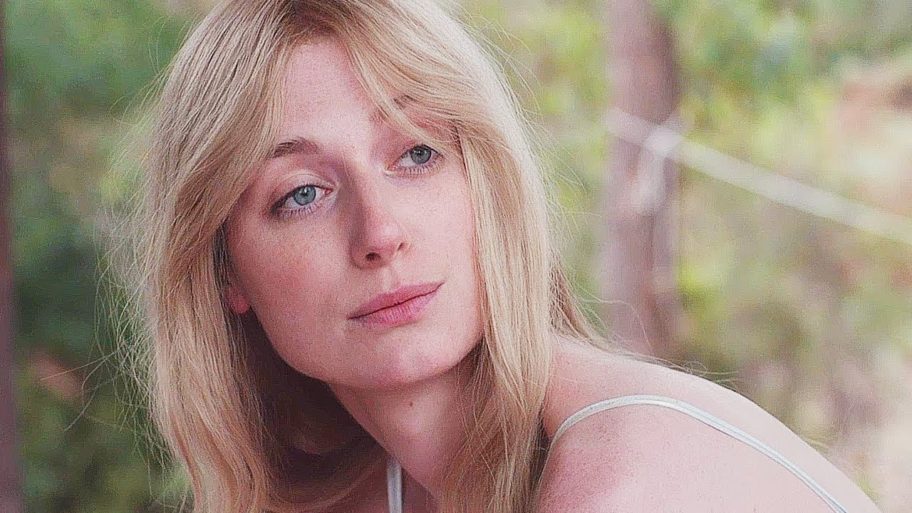

The synopsis for Baker’s directorial debut “follows two teenage boys, the cautious Pikelet and risk-taking Loonie (newcomers Samson Coulter and Ben Spence) growing up in a remote corner of the Western Australian coast in the mid-seventies. Hungry for discovery, the two friends become obsessed with surfing and form an unlikely friendship with the older Sando (Baker), an enigmatic, once famous surfer, and his bored, lonely American wife Eva (Elizabeth Debicki), whose skiing career ended after a knee injury. Sando pushes the competitive youngsters to take risks in the ocean that will test their friendship. And while Sando and Loonie are away surfing, Eva seduces the willing Pikelet.”

Watch the trailer below.

As someone who watched every episode of The Mentalist, it was a special treat to have this conversation with the personable Simon Baker last week at the Crosby Hotel in SoHo.

Danny Peary: You directed episodes of The Mentalist, with great inventiveness, I thought. But even with that experience I’d think it was risky to cast two non-actors in the lead roles for your first feature film. Was it a worry for you or a good challenge considering that it is a movie about risk?

Simon Baker: It was a risk. And like with any risk, it was a challenge in that you can get great stuff or fail miserably. The upside is really up and the downside is really a disaster. But that could happen if you have trained actors. It was a calculated risk worth taking because for me the most important thing was authenticity. For that I needed two young actors who could project their characters’ confidence in the ocean and able to do what was required physically. I thought it would be easier to teach a couple of skilled young surfers how to act than to teach a couple of young actors how to surf. So that’s what I chose to do by casting Sam and Ben.

DP: I would think that it would be another difficult challenge for you as an experienced surfer to convey to viewers who don’t surf what it is like to surf.

SB: I thought that wasn’t possible until I read Tim Winton’s book. Tim is a surfer but he was able to articulate successfully to readers who never surfed what it feels like to be a surfer, to be in the water, to be certain situations. That in a lot of ways was the challenge of making his book into a film, to be able to translate cinematically that feeling of complete emersion in the ocean.

DP: And Samson Coulter and Ben Spence understood that feeling?

SB: They are surfers. Our level of communication benefitted enormously because we all surf. My cinematographer had also surfed all his life and knew that world. So we were all on the same page. There was no one outside the surfing world who was involved with that aspect of the film; there was so much surfing knowledge that we’d already acquired that we didn’t have to talk about it. We understood it all. We knew where everyone should be instinctively, so we didn’t have to yell, “Where are you going? Don’t go there!” We knew what was going to happen, we knew what to do. We knew what our limitations were.

DP: So were all those exciting surfing scenes still difficult?

SB: They were still difficult because we were working in an uncontrollable environment. And we were still trying to tell a story on the water. It’s not just footage. The story has a point of view and we had to express what was happening to those characters in those dramatic scenes on the water as opposed to the surfing sequences. In a lot of narrative films that have surfing in them, the surfing feels like a different movie. I wanted there to be integration. As a surfer it was important for me that the development of the relationships between those characters translates scene by scene from land into the water. I want the audience to live that experience of being in the water through the characters, to have it be intimate.

DP: There is a conversation between Sando, Pikelet, and Lonnie about whether surfing is instinctual or requires intellect. As a sportswriter, I’ve come increasingly to the conclusion that the difference between a successful athlete and an unsuccessful athlete who has the same talent is more confidence and intelligence. Does that apply to surfing and these two kids?

SB: Definitely confidence. These are kids who have grown up in the water, who have surfed from a very early age and have been constantly put into problematic situations where it’s only them and nature and they can get out of them only by using their wits. So they’ve developed a confidence in themselves physically through their knowledge and understanding. I don’t think Sam and Ben were aware of it, but I could see that confidence they have surfing translate to their acting. I could see they had confidence when they were acting. The film is set in the seventies and my recollection of being a teenager then is that we were out and about all the time. It was a physical existence. With my parents, it was, “Just be home before dark.” That was it. We were encouraged to go out. When you are outside with no parents around, you get to figure out your own limitations.

DP: I think Pikelet and Loonie are trying to find their identities. I’m not sure they find it in the right way, especially as kids, in that they come to identify who they are by how they respond to fear of the various waves.

SB: You hit the nail on the head. For me, the primary theme of the film is the search for identity. That to me is the focus. We use fear because it is such a common sensation that motivates us in so many actions. Fear can incite violence; fear can incite paralysis. It can take us in so many directions. So it ties directly to identity in so many ways. Pikelet doesn’t want to be his father. He fears being his father, because he’s dull and he’s ordinary. He worries about being ordinary. He loves his father but rebels against him out of fear of growing up to be as ordinary as him.

DP: And Loonie? Loonie might be intelligent but that never comes out because he does reckless things before he thinks them through.

SB: Loonie’s fear is of not belonging. He wants desperately to be part of something. That’s what motivates him. That’s why he’s fearless in this other world.

DP: He likes eating with Pikelet’s family and being kissed goodnight by Pikelet’s mom when he sleeps over.

SB: He definitely wants to be part of Pikelet’s family at the beginning of the film. He jokes about it but he really wants it. Pikelet thinks his home life is dull, but Loonie really loves going to that house and being part of that family. And later he wants to be Sando’s favorite. He wants to be adored by Sando.

DP: In Tim Winton’s book, Pikelet narrates early on about him and Loonie, “We were friends and rivals.” But I think they aren’t rivals but friendly competitors—in the book they see who can hold his breath longer—until they meet Sandor. He turns them into rivals for his approval. I think the movie conveys this.

SB: Obviously the book goes into more detail but what I tried to illustrate, as with so many things without bogging it down with plot, is that the level of rivalry or competition is exactly what you said—it’s over the attention and affection of Sando. So when Pikelet finds out that Sando has taken Loonie to surf in Indonesia without him, that’s heartbreaking. When two’s company, and three has become a crowd, and you’re the one who is left out—and we’ve all been there—there is heartbreak.

DP: Why does Sando do that, leaving with Loonie without telling Pikelet?

SB: Because Sando is pitting one against the other to create competition, to create a rivalry. It’s exactly that. There is that natural best friends’ competition that always exists but you see Sando trying to fuel it. Earlier, Sando and Pikelet surf Old Smoky while Loonie can only watch with jealously, because he has a broken arm.

DP: Breath has a first-time feature director and the two boys are acting in their first films, but it’s also a rite-of-passage film about firsts. The boys get their first view of the ocean and surfing; they get their first Styrofoam boards; they get their first fiberglass boards; they each experience their first wave—which Pikelet says he’ll ever forget—they get their first wetsuits; they see distant surfing beaches for the first time, Pikelet gets his first girlfriend Queenie, Pikelet experiences sex for the first time with Eva. Also, Loonie is proud to be slightly older than Pikelet because he’s the first to fourteen and fifteen—and he always wants to go first when they surf at new sites. I assume you were thinking of this?

SB: Of course. That’s also part of the competition—“don’t do this, I want to be the one who does it first.”

DP: There is a scene when Sando drops off Pikelet at his house, and Mr. Pike is outside. And they don’t say hello or acknowledge each other. Is that a big moment for you?

SB: Yes. Initially I shot it with Sando nodding to his father and his father giving Sando a small wave. And that was it. But tonally it felt a bit forced. The scene that comes directly after that is at the dinner table and Pikelet’s dad says he’s going to take the dory out and fish on Saturday and Pikelet turns down his invitation to go with him. I didn’t want to put too much of a point on it if they’d waved so I cut the nod and wave and they just glance at each other.

DP: I thought that scene is important because it shows another competition, between Mr. Pike and Sando for Pikelet.

SB: Exactly. Who’s the father figure? I’m losing my son to this guy who isn’t even taking the time to meet me. I love when people notice the small things because there are a lot of details that people don’t get, particularly the first time they see the movie.

DP: In the Press Notes, you say that you really knew the Sando character, that he’s familiar to you. I’d think he’d be a once-in-a-lifetime person you’d meet. He’s not like that to you?

SB: No, there were a few guys like Sando around when I was a kid growing up on the North Coast of New South Wales. I knew those characters. I still do. The weird thing about the culture of surfing is that it has a mysterious mythology that all surfers love. We don’t touch it; we don’t go near it. A lot of these guys like to build this mystery and this mythology around themselves.

DP: It’s aging that gets them, right?

SB: Well, that’s sort of what Sando is experiencing. He’s hurdling toward a mid-life crisis.

DP: So he hangs out with two boys. When playing an enigmatic character like Sando, do you want to totally understand him?

SB: I don’t want the audience to, but I want to understand him. The complexity of Sando has to do with the narcissistic quality to him. The big brave moment that happens, which is Pikelet’s arrival as a young man, is when Pikelet says he doesn’t want to go surfing with Sando and Loonie, it’s not for me. I think Sando has respect for Pikelet at that moment, but at the same time he tells him to get his board out of the back. Pikelet says it’s Sando’s board, but Sando says, “I said it’s your board so get your f***in’ board out of the back.” Which means: you can do your thing but I’m still the f***in’ alpha here. I kind of respect you, perhaps because of your bravery surfing, but don’t think the hierarchal structure is going to change. You’ve now got your own thing, Pikelet, so piss off. Then Sando drives off and he looks straight at Loonie, like, Don’t you abandon me, too! Because at that point, he needs them more than they need him.

DP: Do you think a major reason that Pikelet and Eva start having sex while Sando is away with Loonie is that they both feel betrayed by him?

SB: Yeah, but there is something that builds earlier. The idea is that Pikelet is a more evolved man than Sando is. Eva picks up on that quickly. There’s a sensitivity and self-awareness to Pikelet that Sando has no grasp of, but Eva does. Because Sando is a complete narcissist. Eva, in her frailty and depression, doesn’t articulate it but is a lot more aware of what’s going on underneath it all, in these dynamics. She sees it when Pikelet comes up the stairs while she is napping and is looking at her scarred leg and up her skirt when she wakes up. And he leaves. Pikelet owns up to that moment and there’s a maturity in that. Here’s this kid who is mature enough to acknowledge what he did and apologize. When we were shooting that I cried, I just broke down. Because it was so potent to me.

DP: Late in the book, the adult Pikelet looks back on his affair with Eva and all that happened to him and Loonie with Sando as damaging. What you do is refuse to go where Tim Winton goes in the book. You protect Pikelet and save him from being hurt that way. You keep him grounded and safe and have him make mature decisions. That’s intentional on your part.

SB: That’s completely accurate. That’s exactly what I wanted to do.

DP: Did you discuss that with Tim Winton and your cowriter Gerard Lee?

SB: Tim did an early draft and I had a lot of discussions with him early on about how I wanted to break the book down and remake it as a film. I know Pikelet’s a wreck at later in life in the book, but I saw Tim recently when we were releasing the film in Australia and told him, “Tim, it’s so funny but I don’t remember what’s in the book anymore.”

DP: Both the book and the film deal with the themes of fear and not being ordinary, but I think your film deals more with Pikelet and Loonie dealing with fear and the book deals more with Pikelet not wanting to be ordinary. Do you think that’s true or do you see a connection between facing fear and trying not to be ordinary?

SB: No. I think that “ordinary” was a device that worked better for the book. I think for the film, fear had more potency.

DP: I see another, dangerous theme that fits all these risk-taking characters, including Eva, who wants to be choked during sex, and that is: what can kill you makes you feel alive. Did you want this to be a major theme of your movie?

SB: I think that’s in the film. I think that’s definitely a major theme for Loonie and of Sando and Eva’s existence, but we primarily follow Pikelet’s story and his story is a little more about finding what makes each person tick. He’s a curious, empathic character. He’s curious about Sando, he’s curious about Eva, he’s curious about his parents, and he’s curious about Loonie. His relationship with Loonie was sort of born out of curiosity. Loonie is entertaining to be around but what makes him tick?

DP: In the book, years later Eva hangs herself. When watching the movie, I worried the whole time that she might commit suicide. Did you feel that also?

SB: I wanted the audience to feel a sense of dread. Eva’s moving toward something that’s pretty dark. But then she becomes pregnant and Sando says he’s going to be a father. So maybe things will be brighter for a while. A few people have asked me why I have the adult Pikelet tell us only what happens to Loonie and not what happens to Sando and Eva. And I tell them I don’t want to have truckloads of explanation in his voice over. Remember, the core of this story started with just these two boys.

***I hope everyone will pick up a copy of my new book with Hana Ali about the origins of her father’s most famous quotes:Ali on Ali: Why He Said What He Said When He Said It. (Workman Publishing)

Danny Peary has published 25 books on film and sports, including Cult Movies and Jackie Robinson in Quotes.