Kathleen King's Story: From a Farmstand to a Half-Billion Dollar Business

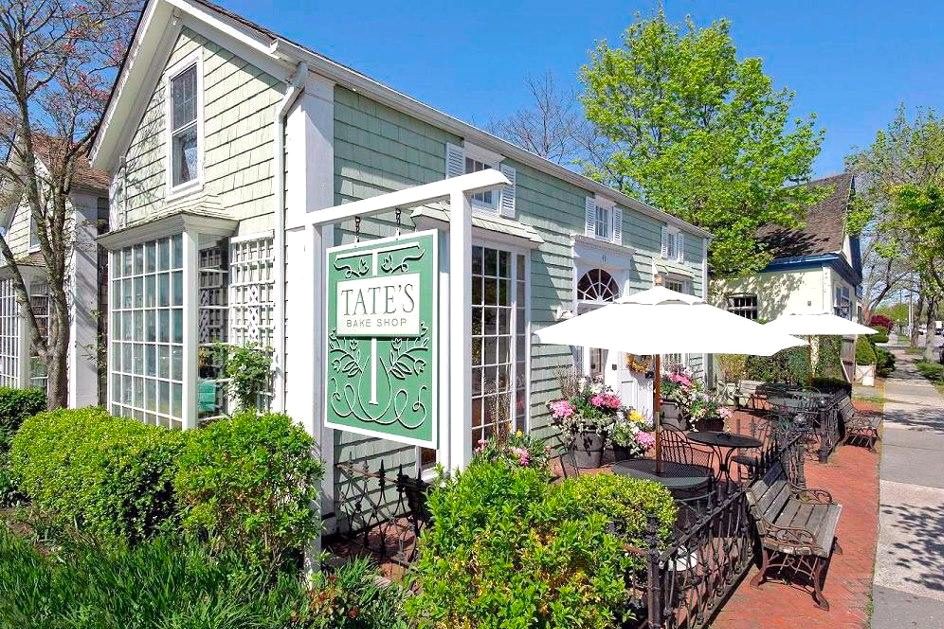

One afternoon in the spring of 1983, I was out doing what I always did in those years, which was walking around with a sales pack under my arm, selling advertising in Dan’s Papers to the local merchants for the upcoming summer. I had been doing this in the springtime for more than 20 years by then, and on that particular day I was on North Sea Road in Southampton, having just had meetings with Leahy Opticians and Herb McCarthy’s Bowden Square restaurant, when I noticed that a small building with a picket fence out front had a new sign. It was a bake shop.

Inside, I came upon a lively young woman in a white apron, taking a tray of cookies out of an oven, who said her name was Kathleen King. She was about 23, and had opened this storefront after selling cookies she baked from the stand in front of her parents’ farm since she was 11—and yes, she wanted an ad.

I was very struck by her, because she reminded me of myself at that age. I told her so. I had been 20 at the time I started writing the newspaper, and I loved doing it. And now I was 43 and still doing it. She told me to have a cookie.

I took a bite. And then, because it was so good, I looked around for a place to sit where I could totally focus on the taste of this cookie. What a cookie.

Little did I know, and surely she did not know either, that here in May of 2018, the cookie business she was running would be sold for $500 million.

Every year after that I sold her an ad in her retail store. It was usually a small ad, 1/12 of a page, and it came with a free 70-word write-up in a section of the paper where I wrote about the stores advertising every week. I’d ask her how things were going. She’d say fine. It was more than fine. Her bags of cookies were becoming celebrated around town. They were fresh, thin, crunchy and made from high-quality ingredients.

The cookie shop was becoming a big success.

In 1999, she was at her bake shop and I was still publishing the newspaper. But things had taken a sudden turn for the worse for her. She was now thinking she might do something else.

It wasn’t that she didn’t enjoy what she did. But now she was 40 and a mother. There were other things to do in life. So she had taken in some partners.

It turned out to be a terrible idea.

In March of 2000, I wrote about it in Dan’s Papers.

“At this point,” I wrote, “neither Kathleen King nor the Weber brothers are talking. There’s only speculation, it’s all going to come out in a courtroom, of course. Still, from what we know so far, we can piece this thing together with the expectation of at least a certain degree of accuracy.”

Actually, Kathleen had told me the whole story. But for the moment, I wasn’t going to write all I knew. Instead, I had offered her my friendship and guidance. I was 60. She was 41. We were both town traditions and maybe I could help. She told me all that had happened. Frankly, the situation was pretty hopeless.

In 1999, Kathleen had sold a majority interest in her bake shop, Kathleen’s Bake Shop, to her longtime bookkeeper, Bob Weber, and his brother Kevin. They would be three partners, each with a one-third interest. The idea would be to expand Kathleen’s cookies nationally.

The Weber brothers would pay her approximately $860,000 as a payout over time. She would remain as CEO. But behind the scenes, they would be creating a factory in Virginia that would produce Kathleen’s cookies on a much larger scale for a soon-to-take-place roll-out.

At first the relationship worked. Kathleen was not moving to Virginia. She remained at the Southampton bake shop while the brothers went south. Checks would be written from Virginia, and cash would come from customers coming to the shop. The bake shop, by the way, was leased to the corporation. As the lessee, the corporation now had control of it.

But things had started going wrong. One was the quality of the product. The Webers were buying ingredients that were cheaper. They told her nobody could taste the difference, and she showed them they could. They did blind taste tests. In these tests, both with the same recipe, she could always pick the ones with the higher cost ingredients. They told her they were in control now. They’d do things their way.

The second thing that happened was that suppliers began calling her in Southampton to tell her they were not being paid by the Webers. And employees were telling her that paychecks were bouncing. What was going on?

“Many of the suppliers and employees are friends. I couldn’t have this. I began taking the cash that came into Southampton and pay it to the suppliers rather than send it to Virginia. I wasn’t going to let them do this.”

I told her they held all the cards. They could do this.

“What can I do?”

“You can either fight or run away.”

“I will fight.”

“It’s a long shot.”

“I just want to bake my cookies,” she said.

Her saying this brought me up short. Some years earlier, I had fallen into a difficult situation with Dan’s Papers. You might have thought it was all peaches and cream for me every year. It wasn’t. I laid out what had happened to me. What I had said when the crisis came to the newspaper was, “I just want to write my stories.”

And here I was still standing. How could I help?

“Are they still paying you for the business?” I asked.

“Yes, it’s supposed to be $10,000 a month. But it’s falling behind. I don’t think they have any money. I want my company back.”

Kathleen had plenty of advice. It would be unfair to say that I was able to give her much good advice. Her situation was very different from what mine had been. But I tried to be there for her. I’d stop in. How’s it going, I’d ask. And she would tell me. There were other people in the community who told me—and her—that regardless of anything, the Webers would soon wish they had nothing to do with this fierce woman. Kathleen was not bending.

Kathleen was not shy about telling people in the community about what was happening. For a time, maybe six months, you couldn’t get Kathleen’s cookies in any of the stores. It appeared the endgame was underway. With that, the Webers came to the store and told her to get out, she was fired.

She was “keeping” the money that was coming in, they claimed. They were going to have her arrested for stealing. During this confrontation, which the employees all witnessed, one of the wives of the Weber brothers became so upset she called the police and demanded an order of protection to keep Kathleen away from her. The request included a phrase reading “…feared for her life.” That was soon amended to “…feared for her livelihood.”

The community rallied behind Kathleen. They picketed in front of her store for two weeks. A big truck carried a banner NO KATHLEEN’S COOKIES UNTIL KATHLEEN IS BACK. The Weber brothers filed a lawsuit demanding the demonstrations stop in front of their store. Their requests were denied. It was freedom of speech. It was on a public road.

“I just want to bake my cookies,” Kathleen told me, repeating the familiar mantra. “Let them have the name. I’ll start over with a new name for my cookies.”

The battle continued. Lawsuits went back and forth. The lousy Kathleen’s Cookies continued to be baked in a factory in Virginia. Here in the Hamptons, the stores were not buying them because the public did not want them. How were they doing elsewhere? Once, on vacation somewhere, I came upon a bag of them. They were very ordinary. Store bought. Store baked. But they had the name.

As Kathleen learned in court, the Webers actually did not have the money to pay Kathleen for her company. They had saddled the business with $600,000 in debt. It was a classic “leveraged buyout.” A nasty thing. And pretty immoral, in my opinion. They hadn’t told Kathleen this, of course, or if they did, she didn’t quite understand it. But it came out in court.

In the end, a judge offered the Webers and Kathleen King a compromise, which they all took. The Webers got Kathleen’s Cookies and the right to the name for going national. Kathleen got the store building back, and also got the right to sell cookies under a new name. And of course, there was still the matter of the $600,000 in debt.

But then the judge ruled that as one-third owner of the business, she actually had to pay herself one-third of the money owed. That was $200,000. She just wanted to bake her cookies.

At the time of the sale, the revenue of Kathleen’s Cookies was reportedly $3 million. That cash flow would continue on to the Webers. As for Kathleen, she started again from nothing, taking a loan for her new business.

Kathleen named the new business “Tate’s Cookies.” The name Tate was her father’s nickname. He had gotten it as a boy. Everybody called him that. It was short for potato, which is what he picked as a boy.

“What do you think will happen to Kathleen’s Cookies?” I asked her. Frankly, I did not see how she could, from scratch, build something up to compete with the old company. But boy was I wrong. The whole town, in fact all of Long Island, was behind Kathleen. And furthermore, these were the wonderful cookies, not the Weber ones. I asked her what she thought would become of the Webers.

“I think they will go out of business,” she said.

In fact, they did.

Three years down the road, Tate’s cookies were back at the $3 million a year mark. Further down the road, amazingly, Tate’s was now selling nationally. Kathleen bought a former abandoned school in East Moriches and converted it into a factory for her product. Soon 40 people were working there, turning out 1.5 million cookies a day and transporting them by truck all around the country. Soon the revenue was five times the $3 million and heading straight up.

In 2014, a principal in the Riverside Corporation, a private equity firm, bought a bag of cookies in Huntington Beach, California. Riverside does not specialize in distressed companies. It specializes in buying companies that have a clearly bright future and helping them get to where they want to go.

They approached Kathleen and made a deal with her. She knew what to do this time. They paid her $100 million, gave her a minority share in the new company, a seat on the board and a position with the company to oversee quality control and how the cookies were to be baked.

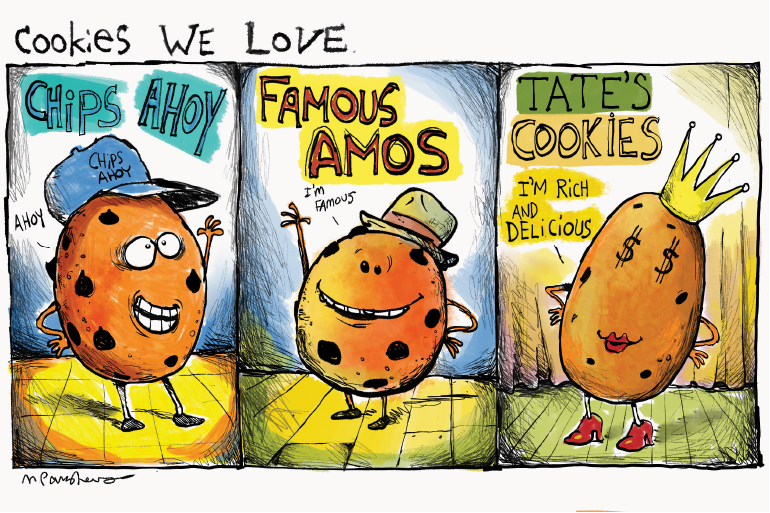

By 2017, Tate’s produced a dozen different products—almost all cookies, such as oatmeal raisin and cranberry walnut—and had them for sale on store shelves in about 85% of all the markets and supermarkets in the country. Tate’s cookies have been entered in national competitions.

They’ve won hands-down in almost all of them, including a contest in Rachael Ray Every Day magazine and a Consumer Reports taste contest of hundreds of brands. And the cookies continued to be entirely baked in East Moriches, and now at a large facility in Westhampton.

And now comes the buyout. Mondeléz International Inc. (largely the successor to Kraft Foods) is buying Tate’s from Riverside for $500 million and will take it international.

It will be its own subdivision of Mondeléz. Sort of what Lexus is to Toyota in the car business. And the pledge is to keep the cookies coming exactly the way that Kathleen, who is retiring, would want them. That’s the whole point.

“This is all I could have wanted,” she says.

Mark Lesko, vice president of economic development at Hofstra University, had this to say to a reporter from Newsday. “You just don’t see $500 million exits every day, certainly not on Long Island,” he said, noting that “regardless of the industry, whether it’s biotech or chocolate chip cookies, if you have developed an amazing product and company, the capital will find you.”

I bet though, for Kathleen, this is not about the money. She will never have to worry about money. Instead, it’s about legacy. She hung in there, had faith in her product, fought for it like a tiger and won, and here she stands, with the best cookie in America made in the same way she made them when she was 11.

What a story.