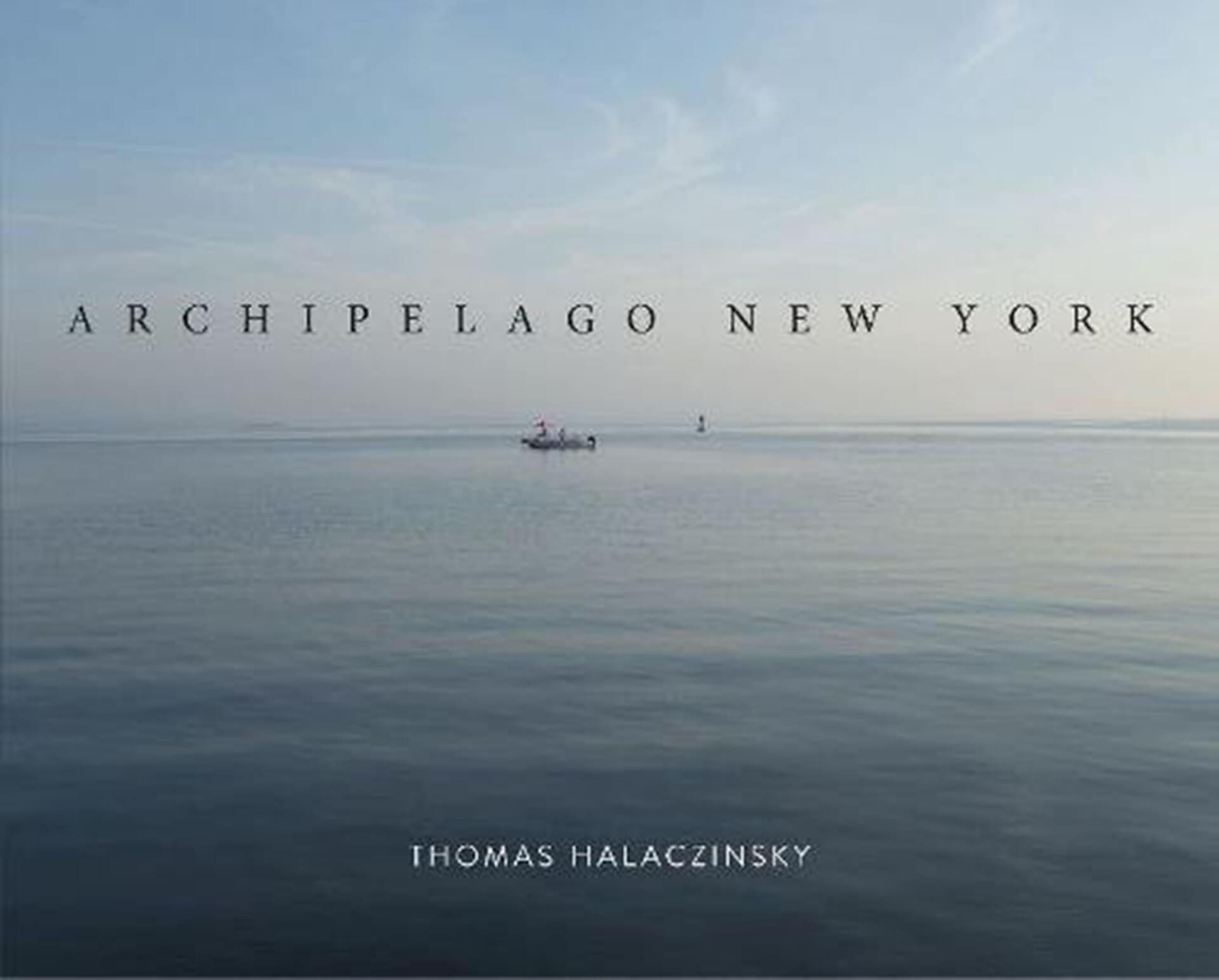

Archipelago New York

This is a beautiful book.

Award-winning documentary filmmaker, writer, and photographer Thomas Halaczinsky manages to bring to his subject — the islands and waterways of New York City and Long Island — not just his skills as a photographer and a sailor, but a sense of wonder that reflects the journey he took to the 70 or so islands he visited by way of his 30-foot sailboat, Sojourn, a sloop outfitted for single-handed sailing on which he lives when he stays in Greenport.

Gorgeous charts accompany brief text for 15 chapters, each headed with nautical notation courtesy National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association. Archipelago New York is more than a picture book, however, even though the magnificent, moody, almost monochrome dark-palette seascapes would enhance any art gallery.

Halaczinsky, who came to New York from Germany in the early 1990s, invests his narrative with love and an inspired desire to tell a bit of history about the harbors and islands he cruised from Manhattan to Fishers, the farthest east of any island in New York State. Leave it to an outsider to remind those in the City of the Manhattoes that they are surrounded by water and why this fact was significant when the islands were first charted in the 17th Century by adventurers looking for “identity and place” (a lot of exploration began with the Dutch explorer, Adriaen Block in 1614).

And leave it to an immigrant to note that the descendants of longtime residents seem unaware of their islands’ rich ethnic history. How telling, he notes, that for centuries the New York archipelago has separated people (the rich living on Manhattan, the poor interred on Potter’s by prisoners on Hart, the sick on Welfare and Brothers’, the criminal on Riker’s).

The word “archipelago” references the Aegean Sea, meaning main sea in olden days. By using this word, rather than “island” in his title, Halaczinsky would appear to invoke a sense of the connectedness of these waterways and land masses that defined civilization. Altogether the islands constitute testimony to the variety of the sea as well as confirm that water is key to “mankind’s future,” an admonition that the aquatic world he treasures is indeed, as “scientists in all disciplines” agree, threatened by climate change and rising sea levels.

Halaczinsky’s no scold or propagandist. More than a geographical and environmental journey, Archipelago New York is a visual and poetic tribute to these islands from a seafaring perspective — an appreciation of what it means to be a lone traveler in a world of beauty, and danger and peace: “No matter how many times I did it, shutting off the engine was always a magical moment. Suddenly, I heard nothing but the sound of the wind and the boat gently pushing through the water” and learned “how time is gauged by the change of light.”

Starting out from Gateway Marina in Brooklyn, Halaczinsky sailed past the marshlands of Jamaica Bay and then into Broad Channel, where settlers built stilt homes that would survive destruction or yield to inexpensive rebuilding. Tidbits include lore about the 1920s when this area with no police precinct was a speakeasy and the rum-running center of city life. He glides by Coney Island and notes in passing Fred Trump’s attempt to industrialize the area.

The photographs, especially those that bleed out to the edge, sometimes a double-page spread, arrest with elegant muted hues and starkly simple composition -— misty mid-horizon line scenes of sea and sky that reinforce the author’s declaration that “seasoned skippers” tend to rely on what they see and hear and intuit rather than on batteries and motors, sticking to “old rules that have regulated life on the water for millennia.”

Still, he’s humbled by what he didn’t fully take into consideration about currents and tidal force, particularly in areas where big container ships ply their trade. “Realizing my weaknesses made me stronger.”

It’s amazing how many native New Yorkers and Long Islanders don’t know about the waters and islands around them, unaware of the neglect of waterfronts in the 1970s and indifferent to the existence of island environments nearby.

Whoever heard of manmade Swinburne and Hoffman in Lower New York Bay, both associated with early days of immigration? Who knew that several islands in The Sound have military history? Or that Fishers (in 1879 it was decided it belonged to New York, not Connecticut) was the forced home of a slave who kept a journal of his brutal existence there, evidence of the fact that one out of five people on Long Island in Revolutionary times were of African descent?

Yes, this is a beautiful book. It is also an important, informative one.