Fruit Trilogy

Watching Eve Ensler’s, Fruit Trilogy, currently at the Lucille Lortel Theater, one feels as if they were entering an existential hell, as in Waiting for Godot. Only here the quest to be rescued from a terrible fate is massaged for a happy ending. And we all know about happy endings, in the corporeal sense.

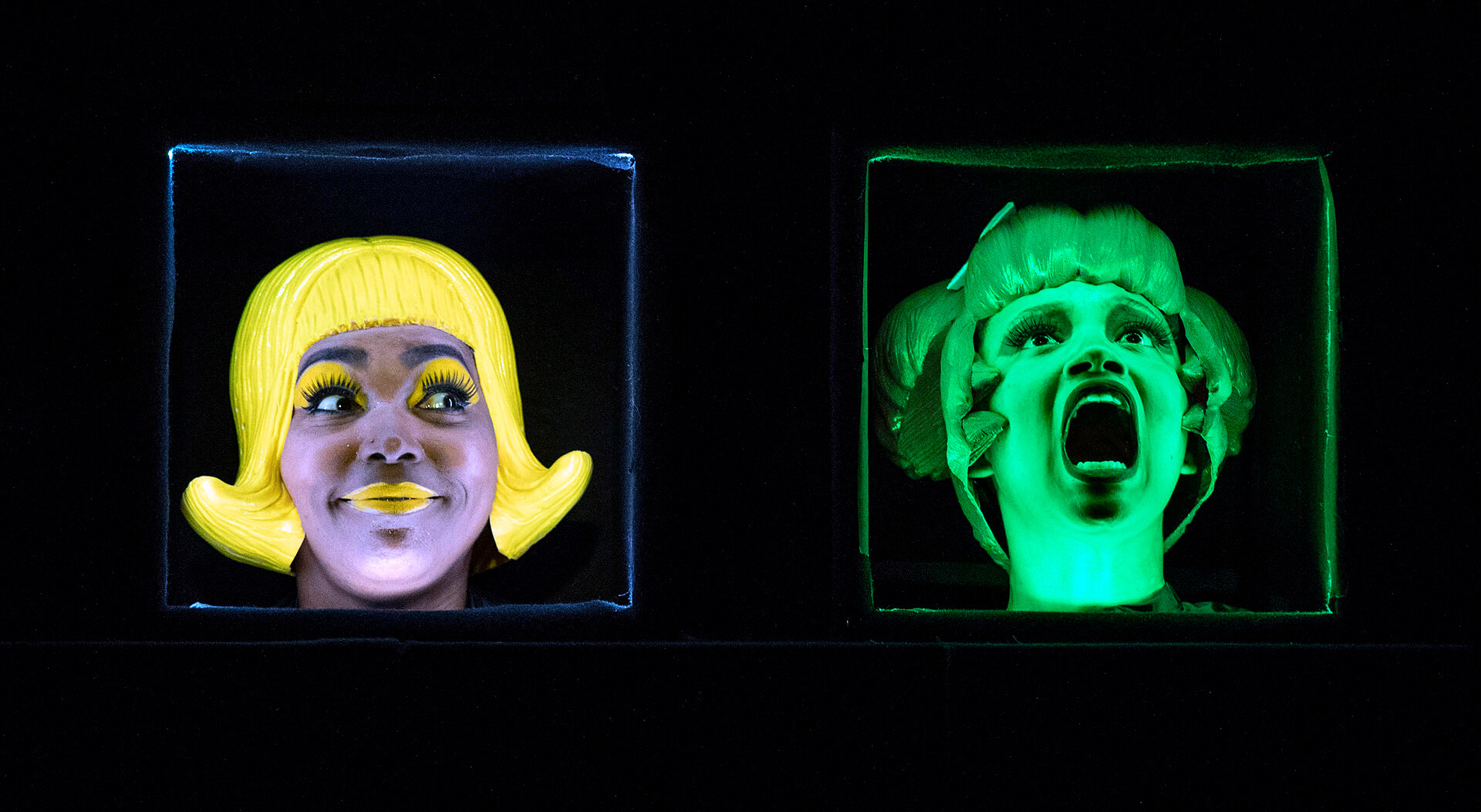

Through two small windows in a solid black screen, the characters, Item 1 and Item 2, appear as two wigs on a shelf. Their tags visible, they wait to see, “Who could be coming? Some soldiers who will leash us and make us crawl? Some husband who will sell us as whores and force us to watch him buying and raping our friends?”

In this first play, Pomegranate, the fate of the two wigs, two women, is expressed by their commodification. And the pomegranate itself serves as a sign of what is to come. Less the spring, in this case, the season when they’re harvested, than a sign of the customers who arrive like victors to carry off the spoils of war.

Who they are, where they’ve been, and how they got here are unanswerable, albeit fundamental questions. Whether their absurd existence is defined by circumstances, or threats, it will ultimately come down to what men dictate. And they, “women more willing to be vile receptacles than (they) are willing to be dead,” suffer that shame.

In the second play, Avocado, the younger of the two characters, performed by Kiersey Clemons, describes being packed into a container with a lot of unripe, hard avocados. Staged by Mark Wendland like a wide screen movie, the setting is free of objects. But the environment, which the actor paints vividly, is so suffocating that she can’t breathe.

It is also the most brutal of the three stories, as this nameless character describes her existence as a woman and a slave. She recounts the abuses of her brother and father, and the whacking that she is repeatedly subjected to by her captors. Describing her experience in abstractions, her monologue is fuming and furious, a litany of startling images, violent deeds, and painful revelries.

And the avocados, the unripe ones she had stuffed herself on, because she was starving and that was all there was to eat, have made her vomit, leaving quite a stench in this contained space. It’s the same experience she had the first time a man shoved himself into her mouth. That scared her and made her vomit.

Indeed, Ensler’s language is graphic, vulgar, and poetic. And the acts described are in large part violent sexual crimes against women, committed for personal gain.

But the third play, Coconuts, in which Liz Mikel portrays a character who discovers herself spiritually and physically, is completely uplifting, and fun. Set in a bathroom, with an altar, the space is mystical — the setting for a uniquely sensual experience. Here, Mikel rubs coconut oil on her skin, beginning with her feet and working the way up to her voluminous breasts.

Oiling her skin, making it so soft “that you melt into it like butter,” she reveals, helps her overcome the deficits — her unruly hair — and all the other ways in which she cannot measure up. As her hands glide and slip over her skin, “moving into the mandala,” as she puts it, she bares into her core, touching herself, seeking her own deliverance.

Sitting alone at the front of the stage, in increasing states of nudity, self-awareness, and pleasure, she asks us not to think of this as theater. She asks, “Can we call it a shared private coconut oil happening? A cosmic body lift, a mystical flesh occurrence?”

That she is a woman who takes pride in her body is Ensler’s message. As the character in Coconut expresses it, “I want to know my body without having to give anything, without having to arch my spine or make idiotic stripper poses or pouty baby faces and high squeaky noises. I want to know my body through you seeing my body, seeing me, not as an instrument of labor or service or as a vehicle or a cavern or an object of worship or a vessel of sin.”

Beyond the daring and sensuality of her performance, Mikel evokes her ceremonious oiling with a wonderful sense of humor, and amazing self-confidence. In fact, both of the actors are incredibly vulnerable and dynamic, as they encounter their many roles as women.

Sensitively directed by Mark Rosenblatt, the characters’ realizations, and their ability to transform, inform the play’s happy ending.

Don Cody’s Yacht

Anthony Giardina’s new drama, Dan Cody’s Yacht at The Manhattan Theater Club, City Center Stage I, plays with the simplicity of boulevard comedy, while addressing complex issues of education and class in America today. But it’s not just the divide between the wealthy and the poor that is being addressed here. More important, it’s about the divide between being real and genuine, versus getting away with easy answers.

In this production, directed by Doug Hughes (Tony Award-winning Doubt), the cards are played openly, and dealt unfairly. As the play begins, Kevin (Rick Holmes) is trying to bribe his son’s English teacher, Cara (Kristen Bush), into giving his lazy son a higher grade. The money is on the table. And while Cara does not accept, she is drawn into the world of this high-powered boastful money manager, with all the hopes and expectations he feeds her.

And Cara also has a child, Angela, a dedicated student, the class poet, whose prospects are just the opposite of Kevin’s son, John. There is no private education in her future, much as she strives to learn, and achieve. That the two teenagers are black and white opposites serves the issue at the heart of the drama.

While the plot is pretty obvious, Giardina manages to hold up the ambiguity of morality in a thoughtful, sophisticated way. It’s not about right and wrong as much as it’s about being true to oneself and knowing how to get results. Indeed, there is no defense of righteous deeds that lead to self-destructive ends, nor crimes targeted to cause others harm. It’s a well nuanced, and well thought out position.

That the play moves so easily and quickly is, of course, a tribute to Hughes’ direction, as well as the very capable cast. Casey Whyland’s Angela evokes our empathy, while John Croft as O’Neill’s son is adorable, and therefore irreprehensible.

And the supporting actors bring their characters into sharp focus, especially Roxanna Hope Radja as Cathy, Cara’s best friend from high school. Still stuck in that small town where Cara is struggling to raise her daughter, Bush’s Cara is a friend you wouldn’t want to lose.

Rick Holmes, as the successful money manager is as charming as he is contriving. The production is smooth, well-paced, and timely.