It’s That Season Again

The official start was June 1, and those of us who live here on the East End know what to expect.

There will be plenty of grumbling. Some of our houses may well be wrecked. Traffic will snarl, and the lines in the grocery stores will be unbearable. And on top of that, it is likely we will lose electricity at some point.

Be prepared to live like this for the next few months until the season is mercifully over.

Hurricane season, that is.

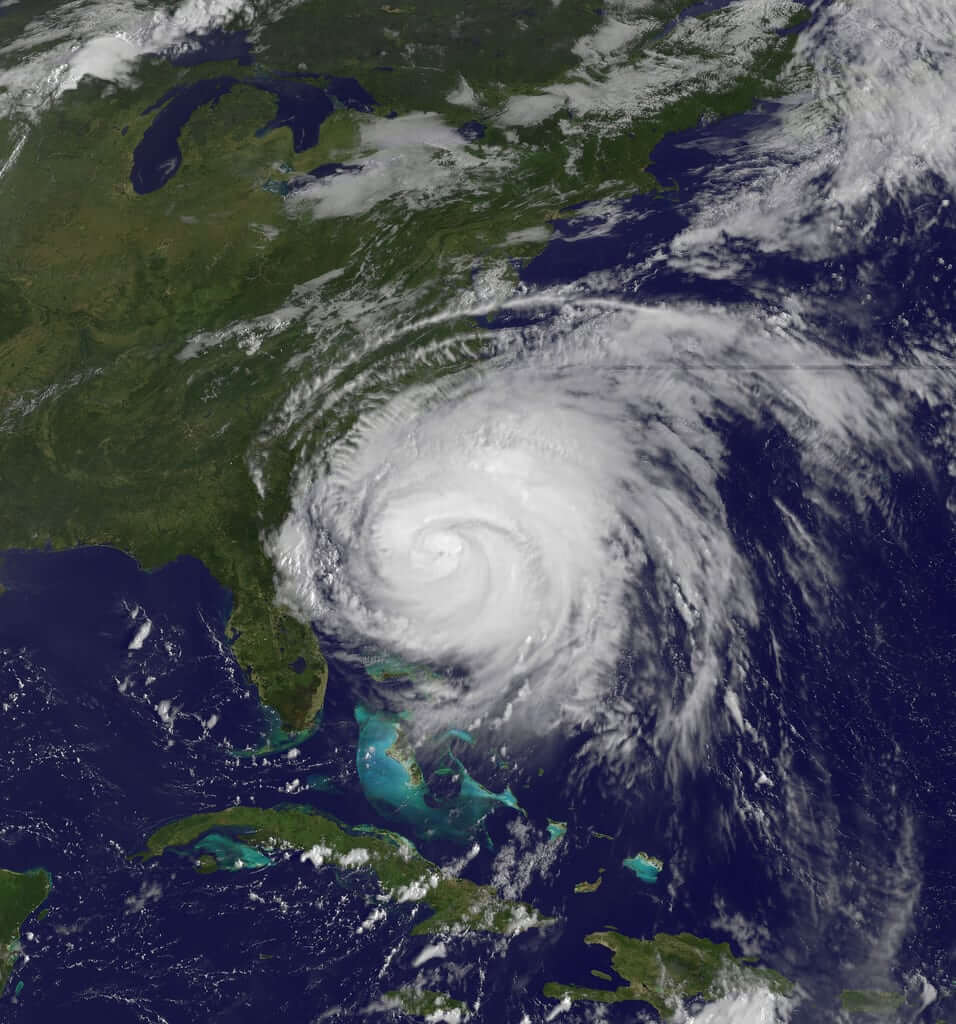

The folks at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Prediction Center have checked in, and their prediction is not a good one: There’s a 35 percent chance of an above-normal hurricane season, according to their computer models.

Spoiler alert: It’s the 80th anniversary of the Hurricane of 1938. “History repeats itself,” warned Southampton Town Highway Superintendent Alex Gregor.

Historically, there are typically 12 major storms each season, six of which develop into hurricanes. Three of those turn into major hurricanes. A “major hurricane” is a term used by the National Hurricane Center for storms that reach maximum sustained one-minute surface winds of at least 115 mph. This is the equivalent of Category 3, 4, and 5 on the Saffir-Simpson scale.

June 1 is a bit early for hurricanes in this neck of the woods. “Early August through October” is the local season, said Jay Engle of the National Hurricane Center New York region. “The peak season is late September to early October.” The season ends officially November 30.

Gerry Bell is a hurricane climate specialist and research meteorologist at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center in Camp Springs, Maryland. He said the La Niña cycle, which will likely be a dominant climate factor this year, tends to support developing storms as opposed to El Niño pattern. “It’s really conducive to hurricanes,” Bell said. The major factor in a North Atlantic hurricane is water temperature. Right now, the ocean’s temperature is a “bit below normal,” Bell said, but it is anticipated to be slightly higher than usual during the summer.

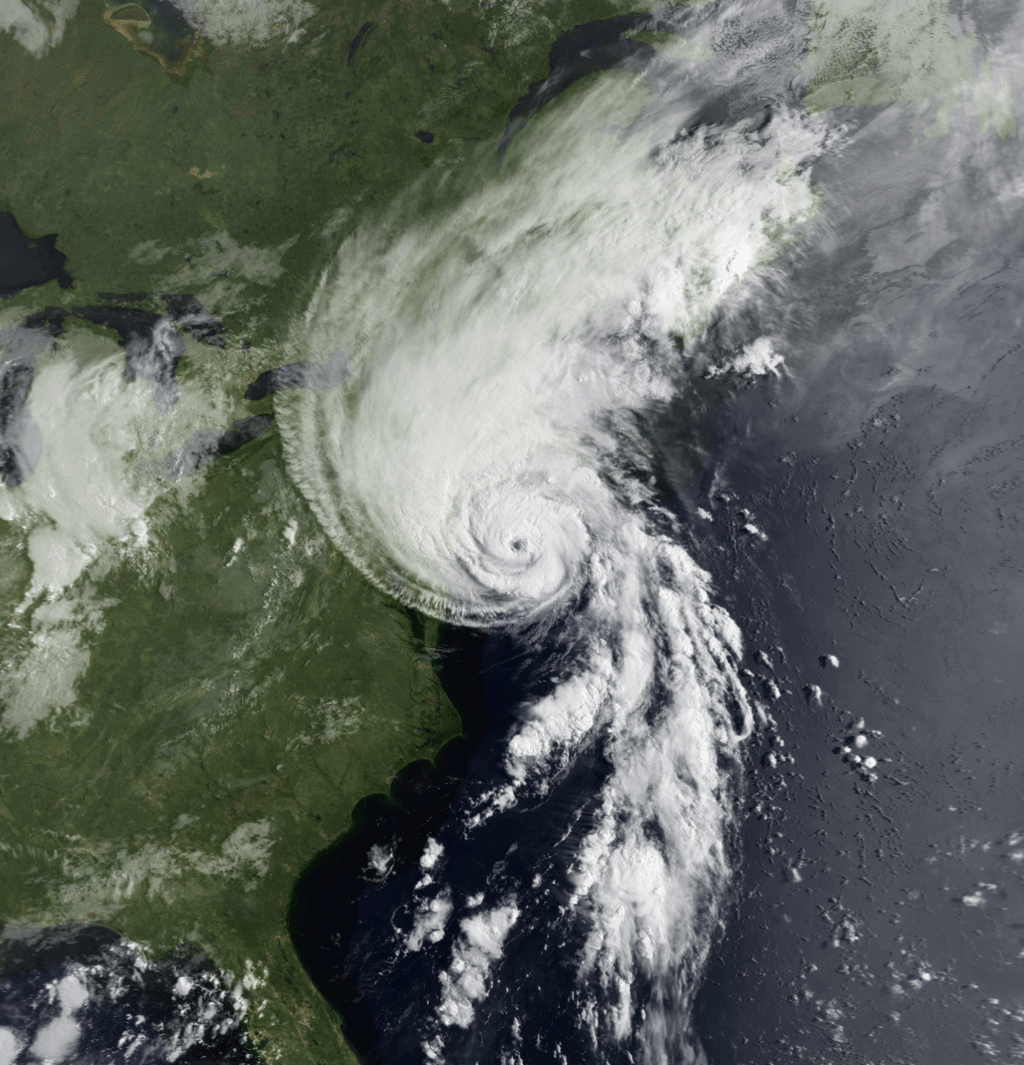

Most locals will remember Hurricane Bob as one of the costliest hurricanes in New England history. The second named storm and first hurricane of the 1991 Atlantic hurricane season, Bob developed from an area of low pressure near the Bahamas on August 16. It brushed the Outer Banks of North Carolina on August 18 and 19, intensifying into a major hurricane. After peaking in intensity with maximum sustained winds of 115 mph, Bob weakened slightly as it approached the coast of New England.

Bob made landfall twice in Rhode Island as a Category 2 hurricane on August 19, first on Block Island and then in Newport, packing winds of 115 miles per hour. It was the earliest landfall of a hurricane in these parts in memory, experts said.

Incidentally, the first Hurricane Bob hit in 1979. That Hurricane Bob was the first Atlantic tropical cyclone to be given a masculine name after the discontinuation of Joint Army/Navy Phonetic Alphabet names. It made landfall in Louisiana on July 16 of that year.

The names chosen for the 20108 hurricanes are Alberto, Beryl, Chris, Debby, Ernesto, Florence, Gordon, Helen, Isaac, Joyce, Kirk, Leslie, Michael, Nadine, Oscar, Patty, Rafael, Sara, Tony, Valerie, and William.

What happens if we have more than 26 hurricanes? The Greek alphabet kicks in.

Most municipalities don’t do anything differently, even if an active hurricane season is forecast. Gregor says he puts in a budget after analyzing his department’s expected expenses, but the amount he requests is typically pared back by the town board.

“The town budgets for a 75-degree day,” Gregor said. “I asked for $3 million for new equipment. They gave me 700,000.”

One thing is for certain: after a hurricane, the cleanup costs are massive. Workers run up overtime as they struggle to make the roads passable again. “FEMA will reimburse us for overtime, but it takes a long time to get the money,” Gregor said. In the interim Gregor dips into reserve funds or requests money from the town’s general fund.

The hurricane of ’38 “was the worst natural disaster in American history, greater than even the Chicago fire or San Francisco earthquake,” according to the New England Journal. It was dubbed “The Long Island Express” and smashed into the East End on September 21. The Daily News reported that “scores of bodies washed ashore a 50-mile stretch of ocean beach” and the death toll was 30 by the following day.

rmurphy@indyeastend.com