Amazing Stories: Hamptons Real Estate Encounters You Can’t Forget

I met a woman the other day who told me about her husband’s prior marriage and how he got out of it. Can’t vouch for the truth of this, but it’s quite a story.

“Tom had fallen in love with the view of the sea in Wainscott at the end of Town Line Road. There was just open dune there then, with a 50-or-so-acre potato farm stretching out up the road. He bought it for about a million six—this was 20 years ago—had a farmhouse moved off the property and built a house to his own specifications directly on the ocean there.

“At the time, he was married to this beautiful but very crazy woman, a big spender. Tom put the property in her name. They’d come out for the month of August. This went on for maybe 10 years.

“One year they came out and were driving down Town Line Road, and about halfway down alongside the property there was a brand new house, just built. A car was in the driveway. Tom was in a rage. He pulled over and jumped out, ran to the front door and started pounding on it. A man answered. Tom screamed at him. ‘YOU BUILT THIS ON MY LAND. HOW DARE YOU. HOW COULD YOU DO THAT.’

“The man looked out at the car, pulled over on the side of the road with the door open. He saw the lady. He pointed at her. She scrunched down in her seat.

“‘I bought this from HER. It’s four acres. What’s wrong with you?’”

“All you could see now was the top of her head.”

“The four acres were right in the middle of the farm. The buyer had a view in every direction, while Tom and his wife no longer did. Tom drove silently down to their oceanfront home. Neither spoke. Finally Tom said, ‘Why did you DO that?’ And she said she had run out of money and didn’t want him to know.

She thought perhaps he wouldn’t notice. Tom put up evergreen trees in a row to try to block the view of this new house. There was a porch attached to the back of Tom’s house. He removed it. But nothing worked. Divorce followed. Then I got him.”

Up until about 1980, many of the big mansions in the Hamptons had paragraphs in their deeds preventing the owners from selling to a “negro, Jew or entertainer.” This was WASP country going back 300 years. Keep the others out.

If you were in one of the groups prohibited but wanted the house, the only way around this rule was to find a friendly WASP man to buy it, remove the paragraph after he bought it and then re-sell it to you.

One such person who did that was Billy Joel. The property was on Further Lane in East Hampton, and when he took me through it he told me of the problem and the friend who helped him. “I’m two out of three,” he said happily.

Another person who did this was Evan Frankel, who wanted to found a synagogue in East Hampton. There was already one in Sag Harbor back then—had been for more than a hundred years—but it was tucked away somewhere and not in any visible spot that might cause offense.

Frankel found a gorgeous and grand mansion for sale in East Hampton, observed that it was smack at the very entrance to East Hampton Village on Woods Lane, and decided it would be perfect to have it as a synagogue where all the blue bloods driving by would be unable to miss it. Then he learned it had the “paragraph.” One friendly Christian later, the sign out front read THE JEWISH CENTER OF EAST HAMPTON.

A similar situation took place in the early 1960s in Southampton, where Jerry Finkelstein, a New York City multi-millionaire in those days, bought a Gin Lane mansion–the biggest mansion in town—and, using the Friendly Christian approach, bought it and proudly put the name FINKELSTEIN on a wooden sign out front. “First Jew in Southampton,” he told me proudly. It was also a proud day for him and his family when then Governor Nelson Rockefeller and his entourage flew out in his private helicopter and landed on the front lawn to confer with Jerry.

Thus did Steven Gaines shortly come to write his popular history of the Hamptons, which he titled Philistines at the Hedgerow.

This is a real estate story from about 1975 that I heard about. At that time, small modern homes existed oceanfront along Dune Road. Dune Road in Bridgehampton runs along a peninsula, east to west, at the back of the Atlantic Ocean sand dunes. Its most westerly terminus is at the cut where Mecox Bay empties into the sea.

The last house on Dune Road had this spectacular view not only of the sea to the south but over and across a vacant lot to the Mecox Bay cut.

Someone bought that lot, however, and proposed to the town to build a house on it. Were he to succeed, the man in the house already there would no longer have that view of the cut. He’d have a view of the side of the new house and then the cut.

The homeowner fought fiercely to prevent this new lot owner from building. He noted that in the zoning, it was now illegal to dig a new water well along that road. He had his, but it was grandfathered in. There were no water pipes coming down Dune Road then. This would put a stop to it. Without the ability to build a well, how could the property owner possibly have a house? He couldn’t. All that money he had spent on that property was for nothing.

The town agreed. But the lot owner appealed the decision by asking for a zoning variance. At the hearing the homeowner once again voiced his objections. The lot owner had a spot where he hoped to dig his well. As a matter of fact, he had found a well pipe under there. It must have had this well before. So it could be grandfathered in, he figured. The town agreed to consider it.

The day came when a member of the zoning committee went down to the lot to examine this well pipe. With him were the lot owner and the homeowner, not talking to each other.

An engineer dug up the pipe and they found it was actually a working well. Following the pipe, they realized it led to the house next door. This was where that homeowner was getting his water. The well for the homeowner was on the property of the lot owner.

Well, the homeowner said, in that case, he would drop his objection. In fact, he was now in favor of this house that should be built next door. And so it was.

The enormous mansion in Water Mill called “Villa Maria” was for many years owned by the Dominican Sisters, a religious order that used the property as a retreat for its nuns. The head of this household once happily gave me a tour of the property. The house had originally been built in the late 19th century for a wealthy New York City banker. In 1931, the religious order Sisters of the Order of St. Dominic bought the house from actress Irene Coleman (stage name Ann Murdagh), who, in the opinion of the order, frequently held licentious, loud and very long parties there.

At that time, the property encompassed not only the waterfront parcel where the mansion stood but also the triangle out front across the way. A few years later, a group of Water Mill residents formed an association to buy that triangle from the nuns and place the great wooden windmill that you see on it today.

“Remembering what had happened with the actors and actresses,” the sister giving me the tour said, “the order offered to sell it to the Water Mill group for $1, provided that if at any time there were licentious, immoral or outrageous behavior on that property, the religious order could buy it back for that dollar.”

I believe that paragraph is in that deed today. So far, it’s been pretty quiet on that triangle.

The great real estate agent in the Hamptons for the wealthy WASP community back in the 1970s and 1980s was Allan Schneider, who built for himself that three-story sandstone English revival building just to the west of Bridgehampton for his main office. Schneider always wore a tie and suit, the jacket sporting a crest on the breast pocket that might have been from English royalty. He said it was the crest of his family. I believe he went to the Episcopal Church in East Hampton in those days. He had a mansion right on Main Street in East Hampton Village.

Once I asked him to tell me of the most unusual sale he’d ever had. He told me about a local merchant who lived in a small split-level house on a half-acre on Hayground Road, north of the highway.

“He wanted to list it for sale with me,” he said. “I told him it might fetch about $85,000, that was all. He said he wanted the listing at $300,000. He was adamant. I took it on, but I’d be driving people around and we’d pass that house and I’d note it was for sale—the sign was out front—but it was asking $300,000. People would scoff at it. So we’d press on.

“After about a year, I drove by it with this young couple and they saw the sign out front and asked me the price, and I told them and they said it was just perfect for them. Just driving by they were in love with it. I was dumbfounded. They asked if I could bid $290,000. I agreed to do so. The merchant refused it. In the end, he got the full $300,000.”

Allan Schneider died at the age of 54 during a dinner when he choked on a piece of steak and had a heart attack. At his funeral, his Jewish parents, Saul and Celia Schneider, both in their early 80s, came up from Fort Lauderdale, and nobody said a word to them about how Schneider, in life, had conducted himself.

Here are two more recent stories.

Around the year 2000, a Wall Street titan purchased a farm on Gibson Lane in Sagaponack, and after many a go around with the town, had the farmhouse torn down and replaced with a magnificent 6,200-square-foot architectural prize-winning mansion. It took him more than a year to build this house, which then wound up going to his wife in their divorce settlement. Another Wall Street titan, a man who’d formerly worked for the first one, bought the property, decided he didn’t like the house the former owner had built there—this house had barely been lived in, maybe just a few times—and so had that torn down and built one twice as big on the site.

In Southampton about that same time, a man bought an oceanfront property that had a main house, a cottage for guests and another small house. The buyer wanted to tear the two smaller houses down and, using that square footage, attach an addition of that size to the main house. These three buildings on this property had preceded zoning and so were grandfathered in.

But once torn down, the square footage was gone. You couldn’t build bigger than what was the main house. That was the maximum with current zoning. In the end, the buyer left the houses where they were and created an enormous basement that sat underneath all three. Above ground they looked the same. But access to them was through the exercise room, the spa, the movie studio and whatever else the buyer dreamed up for his enormous basement.

This 322-foot long basement under the dunes also served as a giant cofferdam project against ocean turbulence during storms. It might have qualified as a “hard structure,” which is illegal, but since it was under a house it was a “basement.” This project sits east of Coopers Beach in Southampton. An ingenious but expensive solution to a problem.

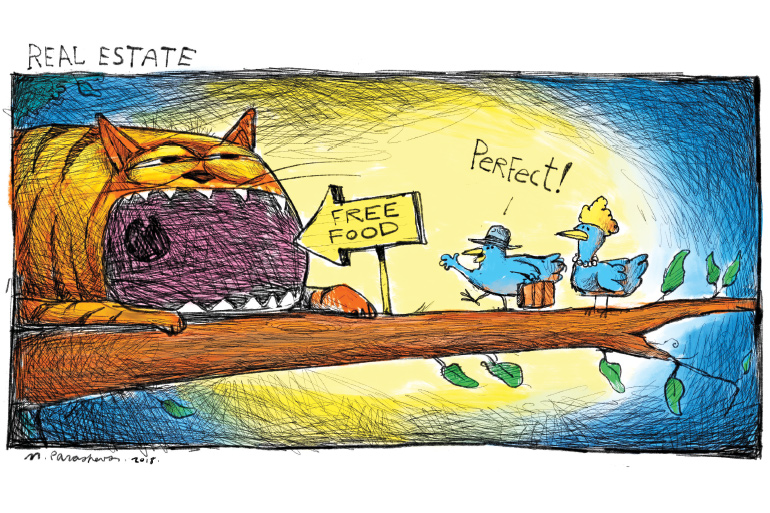

Now Jay-Z and Beyoncé have bought a house on Georgica Pond, moved in and discover the owner of the property next door wants to build a house that would block their view in one direction. And so, as it always does, the fur will fly.