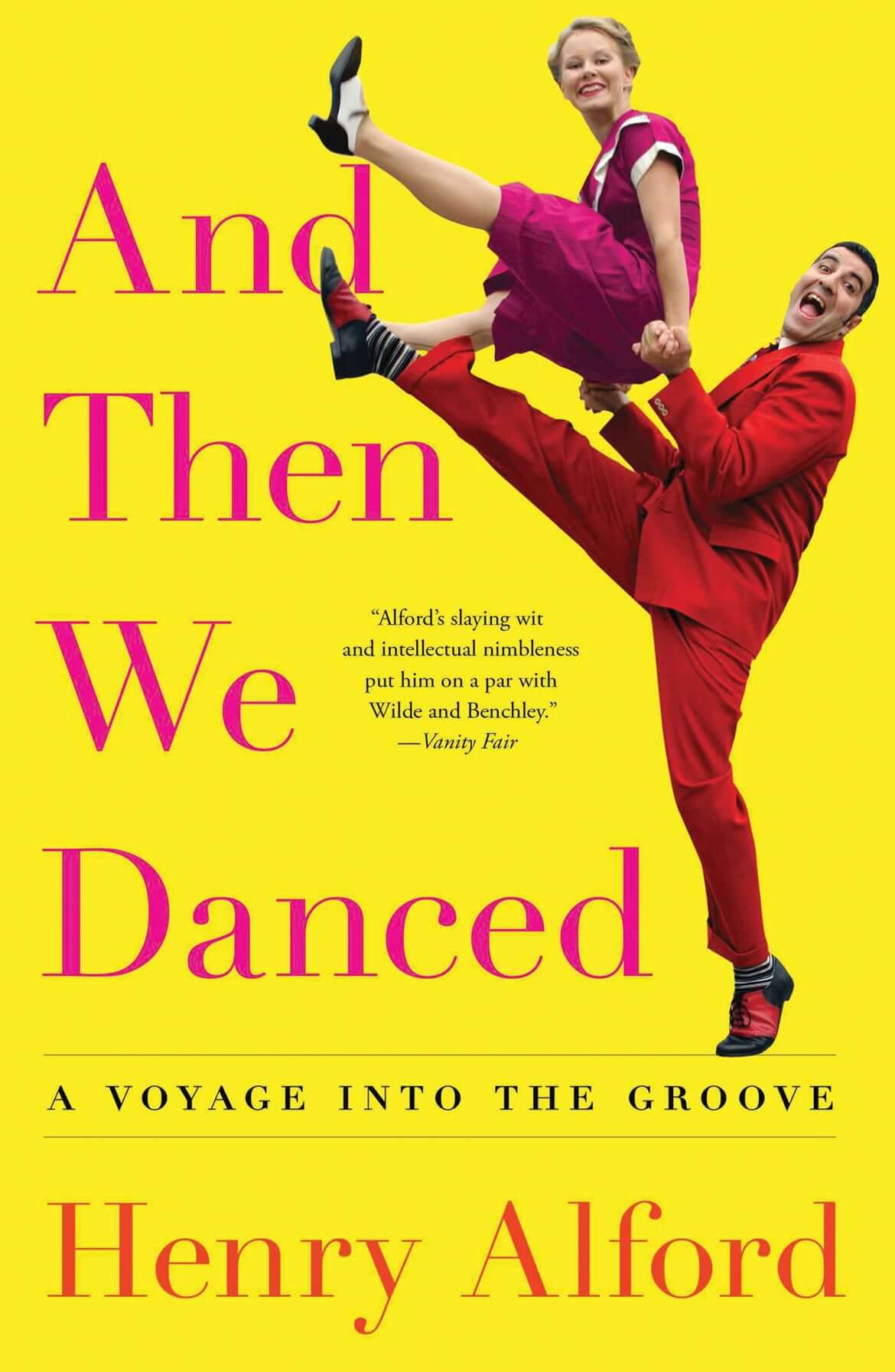

And Then We Danced

It’s a kind of burden when someone says, “You gotta read this book. It’s hilarious.” Unlike wit, which reflects an astuteness of perception or judgment and need not be funny, humor, a broader and more democratic human attribute, often depends on societal norms which can change over time, or differ depending on culture or country. Arguably, humor is difficult to translate, given the psychological weight it bears.

And Then We Danced by award-winning writer Henry Alford, who has described himself as a “participatory journalist” (shades of Truman Capote and Norman Mailer!), has been critically hailed as a “hilarious” memoir about the 56-year old author’s late-life love of dance in all its forms and functions.

These include, as the nine chapters indicate, an exploration of dance as Social Entrée, Politics, Rebellion, Emotion and Release, Pure Physicality, Religion and Spirituality, Nostalgia, Intimacy and Socializing, and Healing. The book is also a joyous celebration of Alford’s sexuality and of his partner, Greg.

Impressively researched history on all manner of dance, the book not only informs but will likely prove inspirational to anyone feeling uneasy about his or her place in the world.

Alford believes that anyone can dance and should — at jams, clubs, parties and, most of all, in one’s own living room. He’s had some wild experiences and has obviously spent a lot of time reading about dance and talking with dancers, both pro and amateur.

Alford not only immersed himself in scholarly and popular literature on dance, he spent a lot of time talking with dancers. A particular strength of the book is its conversational, self-deprecating, in-your–face tone. It’s also democratic: Alford is wild about all dance — tap, ballet, funk, ballroom, hip hop, jazz, swing, contact improv (his fave), seeing no one form as culturally more important than another.

He even got to dance with “luminaries,” though he was a beginner. And he continues to dance, even when his back goes out.

He argues persuasively that dance is unique among art forms, probably the fastest and most consistent way to establish — and secure — a relationship with a lover or friend, and an all-embracing activity, utilizing “several brain functions at once — emotional, logical, kinesthetic, musical.”

Although he’s a privileged preppie (he and his friends as teens got into Studio 54), he’s easy hanging out with all ages and income classes, and he’s especially pleased at the time he’s spent helping teach Alzheimer’s patients to dance as a way to stay in the game. On his way out the door, after one ballroom activity, he’s moved beyond himself to see propped up near the entrance “two pairs of crutches and a wheelchair.”

One of the highlights of the book are the mini bios and telling anecdotes about various stars, among them George Balanchine (who inaugurated “ballets that have no plots”), Bob Fosse, Paul Taylor, Twyla Tharp, Arthur Murray (who suppressed being Jewish), Isadora Duncan, and Savion Glover.

Alford seems to know everything about and everyone involved in classical ballet, musical theatre, and down and dirty dancing. He subscribes to the belief that “good dance is better than sex” because it is so sensual, and so much more.

The style of the book, however, may at times prove challenging because of occasional sophisticated allusions, strained similes and metaphors, and undefined urban lingo. For sure, though, the tidbits are fascinating, among them learning about Fred Astaire’s penchant for violence. (Astaire once phoned Michael Jackson to say, “Man, you really put them on their asses last night. . . you’re an angry dancer. I’m the same way.”)

Gene Kelly? A “hothead,” given to verbal abuse and fist fighting.

As for himself, Alford writes, “I’m not an angry person and thus have no need to channel fury into a fiery display of scissor-sharp cabrioles and pelvic pops.”

Alford may be getting on in years, but is as ecstatic as ever about dancing, putting in as many as six hours a week, mostly on weekends (“I’m a gentleman dancer — which is not code for ‘Edwardian male prostitute’”). “Musicians use instruments, writers use keyboards and paper, painters use paint and canvas,” he writes, “but a dancer has only his own body. This is both a blessing and a curse.”

In And Then We Danced, the priority is clear. Alford caught the dance bug when he was 49 but still likes to think of himself as 31, “seasoned enough not to commit the atrocities of adolescence and my early twenties, but not so old as to have cut off any of my options in life.” Amen.