'Boats, Barns and Bootlegging' at the Bridgehampton Museum

After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all the territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.

—U.S. Constitution amendment XVIII, section 1

On January 16, 1920, after decades of effort, the 18th amendment, better known as the Volstead Act, went into effect, ushering in the era we know today as Prohibition. The act grew from the earlier temperance movement of the 1830s, which tried to tackle the stunningly excessive drinking problems of the average American. It’s estimated that the average American at the time consumed 90 bottles of 80-proof liquor per year. That’s four shots a day, every day, or a lot of liquor. As the problem grew worse, women took to churches hoping to enlist clergy in their crusade and, perhaps, to put the fear of a sober god into the hearts of their thirsty husbands. The clergy obliged and in the following decades the temperance movement gained momentum. Soon, politicians picked up the fight.

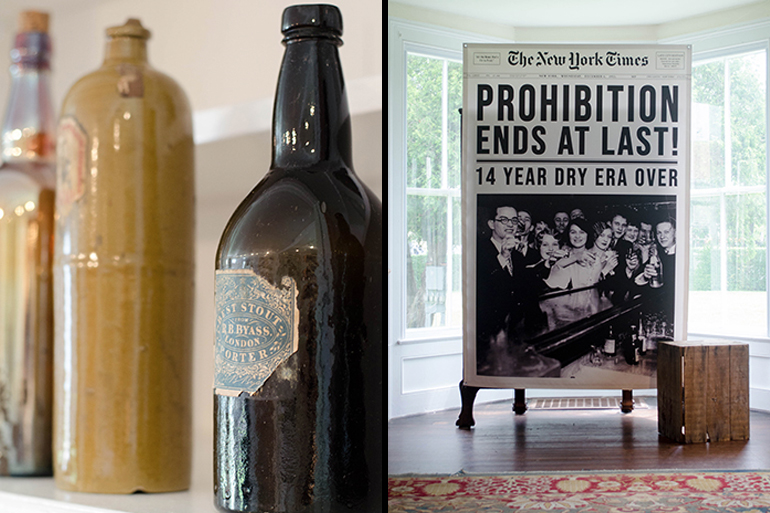

This is where Bridgehampton Museum’s new exhibition, Boats, Barns and Bootlegging, begins. The first room of this two-room exhibition focuses on the politics of Prohibition, covering the years from the beginning of the temperance movement to the adoption of 18th Amendment. Here, a visitor sees various political advertisements and, under glass, finds a collection of 19th and 20th century pro-Prohibition campaign pins. The same pins are featured as blown-up images on poster board that line the walls of the room. There you’ll see popular slogans such as “Join the Camels” and “Safety First Vote Dry.” It was the images of children, however, that might have won over those on the fence about Prohibition. Several buttons feature one or more children and slogans such as “Vote No License For My Sake” and “Vote No For Me.” One will also see a campaign button for the Prohibition Party’s ironically named presidential candidate Dr. Silas C. Swallows.

The exhibition continues into a second room, covering the time until, as a larger-than-life New York Times front page says, “Prohibition Ends at Last, 14 Year Dry Era Over.” The centerpiece of this room, focusing more on the East End during Prohibition, is a big red bathtub, taken from the Nathaniel Rogers House, which explains the origins of “bathtub gin.”

What happened on the East End during the Prohibition years is the stuff of legend, complete with bootleggers, rumrunners and speakeasies. Its proximity to New York and its seafaring history made Long Island the center of liquor importation from Europe, Canada and the Caribbean. The general practice was to have large supply ships anchored in international waters met by fishermen and farmers in smaller craft, who’d fill up and then take their stock ashore and deliver it to waiting trucks.

Claudio’s Restaurant in Greenport, which at that time sat on stilts, was one such place these smaller craft would offload their goods through trap doors. During Prohibition, Claudio’s was a fine French restaurant downstairs, while the upstairs became a lively place for imbibing illegal spirits. Behind the glass door, at the left of the bar, was a dumb waiter that let folks downstairs join in the fun too, sipping from their “water” glasses.

Of course, Prohibition was unpopular and impossible to fully enforce. By 1930, more than 1,000 speakeasies had popped up in Suffolk County, four of which were reported by the East Hampton Star on January 2, 1930 to have been raided. All four were run by women and, as a testament to the money to be made by bootlegging, all four had enough cash on hand—just two months after Black Tuesday, the day the Great Depression began—to cover the $1,500 bail, the equivalent of about $25,000 today.

In February 1933, Congress proposed the 21st Amendment, which repealed the 18th, and ratified it on December 5 of that year.

Boats, Barns and Bootlegging runs through October 8 at the Bridgehampton Museum, 2368 Montauk Highway, Bridgehampton. 631-537-1088, bhmuseum.org