18th Century Mystery: Giant Cannons from British Man o’ War Scuttled Off Montauk

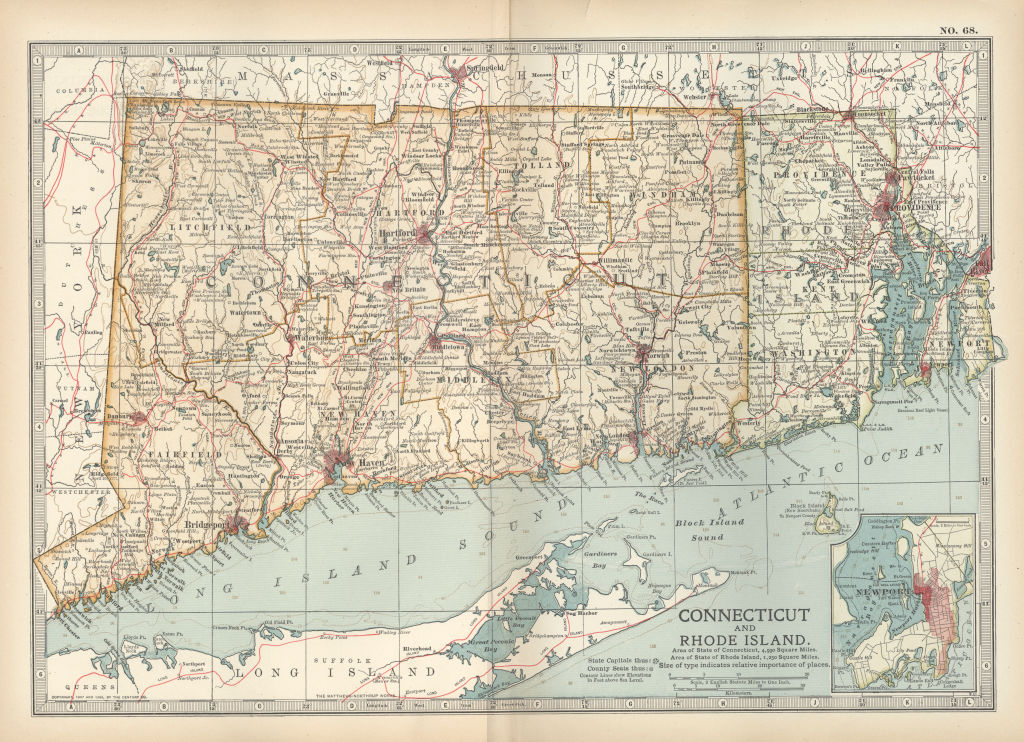

On July 24, 1781, a resident of Groton, Connecticut named Joseph Woodbridge wrote a brief letter to General George Washington that is of considerable interest to the Hamptons. He had guns for sale.

“Since the Misfortune that Befel (sic) the Enemys Ship Culloden in the Sound (at Montauk,) I have had the good fortune to Get up Sixteen of her upper tier Guns, 32 Pounders—and understanding that your Excellency has had Occasion to Direct a Number of Heavy Cannon to be Transported Eastward for the Use of the Army…I should be very happy in Supplying Your Excellency with the Above, upon Reasonable Terms, and Convenient Pay for the Continent.”

The HMS Culloden—a big British Man o’ War, nearly 200 feet long and packing 74 guns in three rows along each side–came ashore and wrecked on the beach at Wills Point in Montauk during a blizzard in January of that year. It’s still there today, much of it, the only shipwreck site in the United States ever to be designated a National Historic Site. You can skin dive and scuba there. But since 1991, when it received that designation, you’ve not been allowed to take any souvenirs off of it.

So what’s the problem here, and why is this letter so important?

During the winter of 1780–81 the War for Independence was still underway. George Washington’s army, for the most part, was still in winter quarters in encampments in Connecticut and New Jersey. The British fleet, which included nine “ships of the line” (HMS Culloden included), was enforcing a blockade of the northeast. No ships were allowed in, and none were allowed out.

The only threat to the blockade was the French fleet, docked at Newport and pinned in there by the British. Allied with the patriots, it might have been a match in an all-out battle. But it was not venturing out. The French admiral did not have charts of the treacherous waters around New York City, and he feared he could lose an encounter because of that and so stayed put.

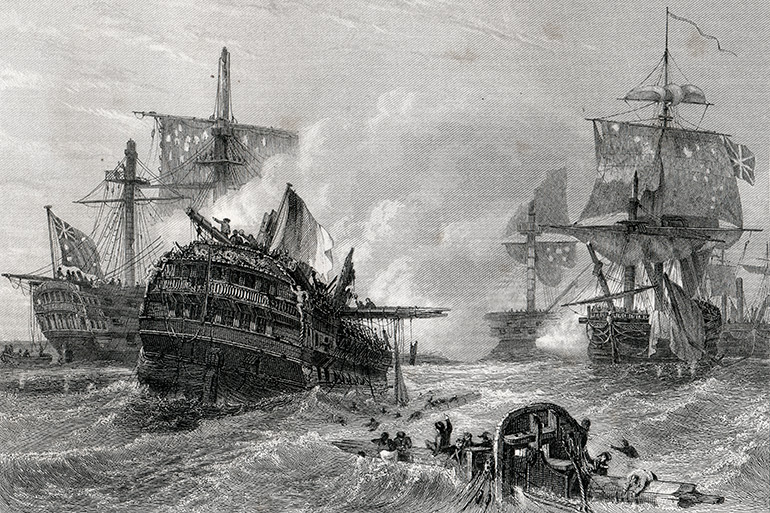

On the other hand, spies for the British informed British headquarters in Manhattan that three French Men o’ War were preparing to try to run the blockade. It never happened. But the British, believing it might, sent HMS Culloden, HMS Bedford and HMS America out into Long Island Sound to make an engagement.

A big Nor’easter swept across the Sound while the ships were out off Montauk. The Bedford lost all of her masts and was beached on the North Shore of Long Island and the America went missing for three days before finding its way back to its position in New York Harbor, but the Culloden lost two of her three masts and then her rudder. The storm abated, but the Culloden drifted out of control, finally sliding up onto the sand at Wills Point, Montauk—since re-named Culloden Point because of this shipwreck.

It should be noted that the Culloden was one of His Majesty’s newest Men o’ War. Built in England, one year before the war started, she was entirely sheathed in copper below the waterline. This was a new British development. Copper sloughed off the water as you cut through the sea, where wood on the bottom would slow you down. As a result, the Culloden could outrun any other nation’s Men o’ War—a tremendous advantage in combat. And only a few of Her Majesty’s ships had this advancement.

Indeed, a year earlier, the Culloden and other copper-sheathed ships heading for America encountered a small Spanish fleet off Portugal, overtook them as they tried to run away, and cut them to pieces. That was the Culloden’s first—and only—military encounter.

As for armaments, on the lowest level just above the waterline, called the main gun deck, 28 enormous upper-tier cannons stuck out through square holes in the ship, able to obliterate anything that came up alongside. Each gun weighed 6,500 pounds, and each could fire a 32-pound cannonball. On a middle deck just above, there were 24 smaller cannons, each able to fire an 18-inch cannonball. On the quarterdeck, there were 14 cannons that could fire nine-pound cannonballs. And in the forecastle, there were four more nine pounders. Even coming right at you, the ship could give you a small pasting.

The Americans had nothing that could battle with this British fleet other than a few packet boats. A British Man o’ War, appearing over the horizon, struck fear into American soldiers. Those ships would have their way with them.

When the Culloden got stuck in the sand a few hundred feet off Wills Point, efforts were made to haul her off before the sea might break her up. They all failed. Help would have to be found. The situation was somewhat urgent, because this grand Man o’ War would be of great value to the Americans. She might be towed off the sand. Or her powerful guns might be taken off by the rebels, with teams of oxen dragging the large 32-pounders inland—they weighed nearly four tons each.

For a while, the 560-man crew members remained onboard the ship in the hopes she’d be gotten off—and also to keep warm. But soon the captain ordered a big complement of his sailors to push each of the big 32-pounders out of the deck portholes so they could pitch into the sea. Then he ordered all the men to come ashore with provisions and tents and whatever else they could carry. Eventually, they were able to get off the nine-pounders and the eighteen pounders. On the sand, the crew built fires and set up a camp for themselves. They waited.

Montauk at that time was essentially uninhabited. There was no lighthouse yet. There were several homes, called First, Second and Third House (two of the three exist today as museums), used by the livestock cowboys for shelter during the summertime, when all the cattle in the Hamptons got driven out there to feast and get fattened up on the sweet grass of Montauk’s rolling hills.

But this was January—a bitter cold month. And the only human habitation was a few families of the Montaukett Indian tribe living in huts in the woods. These men, women and children were all that remained of the great tribe the white men had come upon 140 years earlier. Almost all had died of white men’s diseases.

It is not known how long the crew of the Culloden remained on the beach in Montauk. It might have been for the next 12 hours or so. A few sailors had rowed off to get help and report what happened. The nearest British encampment was on the wharf in the whaling port of Sag Harbor, 22 miles away. This might take strong rowers six hours. The British occupied all of New York City and Long Island then. They had won the Battle of Brooklyn and chased off Washington when the war first broke out. The captain knew the ship would be safe for a while, anyway. But something would have to be done. And so he ordered something a captain never wants to do—burn the ship to the waterline. Make it useless to the rebels. And that was done.

A few days later, the HMS Bedford arrived off Montauk and all the nine pounders and eighteen pounders, together with whatever else they could find of value, were loaded up from the beach and carted off. The salvaging of the Culloden continued on through March, April and May. With that, the Culloden was left to its fate, a monstrous shipwreck down on the sand in the shallow waters of Long Island Sound off Wills Point.

Then came June and Mr. Woodbridge’s letter from Groton, Connecticut to Washington.

Here’s some background. By the fall of 1780, the English had decided to march the majority of their forces south to North and South Carolina and Virginia. Still in possession of Manhattan Island and Long Island, they kept a large force there to repel any attacks from patriots coming from Connecticut or Rhode Island—still under rebel control. The idea in the War Admiralty in London was to subjugate the South, keep Manhattan, and the rebels would fall.

Washington, in New Jersey, learning of the British marauding through the South, sent General Greene with a small rebel army south to harass the British, while he indeed planned to attack Manhattan. The French had landed at Newport with 5,000 French regulars in the fall of 1780. Yes, they were pinned down there with the fleet unable to break out.

But Washington was itching for a fight. He ordered the French to rendezvous with him at Dobbs Ferry in Westchester County in May to try to retake Manhattan. A lot would depend on the French navy breaking out and attacking the British fleet at Manhattan. But the French, with their map problem, were still balking at this idea.

The plan was still being discussed when Woodbridge sent his letter in June. But then something happened that changed everything. And it is why Washington never took Woodbridge up on his order.

On July 9, six months after the wreck of the Culloden, General Washington received word that a massive French armada of 35 warships was headed to America—not to Manhattan, but to the Chesapeake Bay, between Virginia and Maryland. Washington immediately saw what could happen if he could move fast.

Forget Manhattan. He would take the 5,000 French regulars and about 10,000 of his own men overland to the Chesapeake. He’d order General Greene to close in from the south and west. He’d come down from the North and with the French fleet offshore in the bay, pin the 15,000 British troops under Cornwallis at the port of Yorktown.

And that’s what happened. Cornwallis, once realizing what was underway, desperately tried to contact the fleet at Manhattan asking the British navy to come down and evacuate him, and eventually, the British fleet came. But it was too late.

Three days before the British arrived, after a fierce month-long bombardment by those surrounding him, Cornwallis flew a white flag and surrendered to George Washington and General Greene on October 19, 1781. When the British fleet got there, they encountered the French fleet. And so, in the waters off Yorktown, a fierce but inconclusive sea battle took place, after which the British fleet turned around and headed back to Manhattan to refit and repair. Washington’s victory held.

That surrender at Yorktown, in essence, caused the British to give up the battle to keep the colonies in line, resulting in the founding of the United States several years later and all that has come since.

But what of Woodbridge’s letter to Washington on June 24, 1781? He was offering up 18 of the 24 enormous cannons that, when last heard from, had been pushed overboard into the sea at Montauk. How in the world did Woodbridge salvage them? Or did he? They each weighed more than three tons. Only oxen and horses could have gotten them up. But there is no record of it.

What we do know is that so far, only a few of the big 32 pounders have been salvaged. And since 1991, when the site was protected by the U.S. Government, none further were taken, or even found.

Are they still down there? Or are they somewhere in Connecticut? Only time will tell.