Silvera exhibit puts memory into motion

Vivian Silvera is a globe trotter, hailing from international cities Hong Kong, Sao Paulo, and then New York City. Upon her move to New York at 15 years old, she began visiting the Hamptons with her family and found beauty in the area.

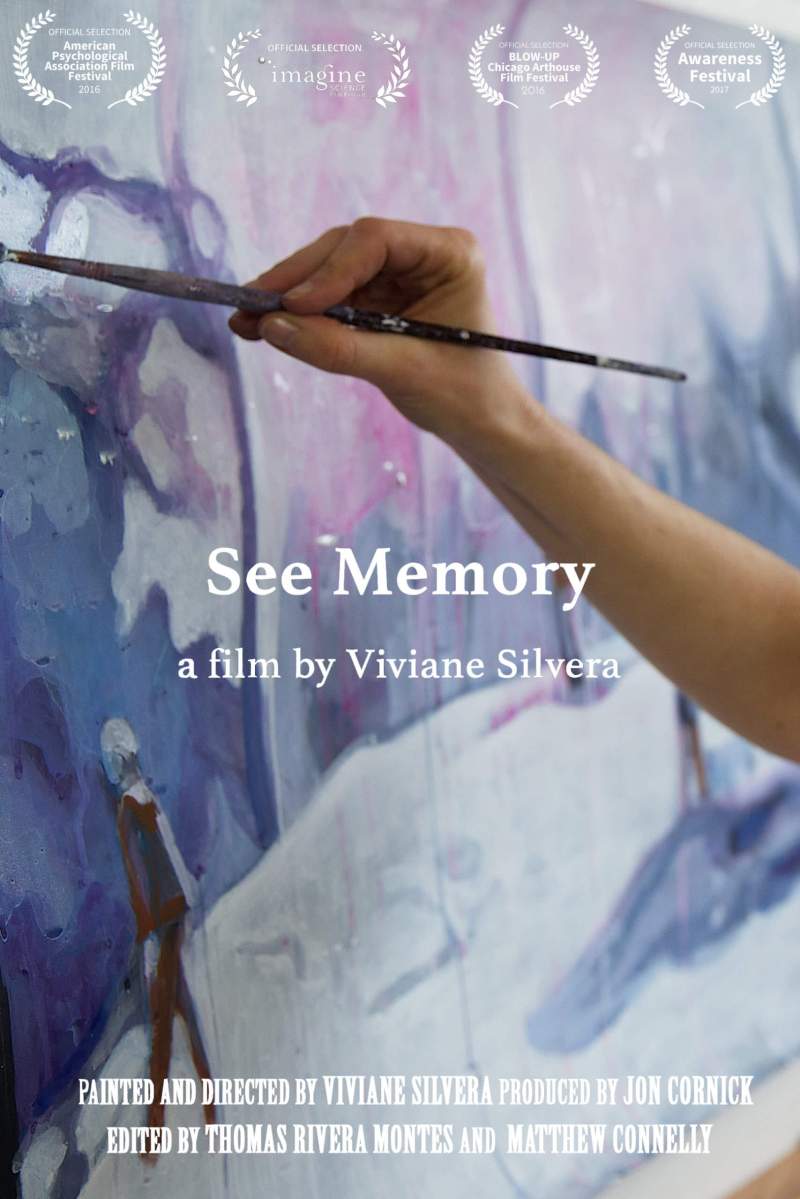

Now on view at The Spur in Southampton is her exhibit “See Memory: The Paintings and Films of Vivian Silvera.” Silvera takes 10,000 painted stills and creates a 15-minute film exploring the nature of memory through the science of remembering. Surrounding the walls of The Spur are 23 paintings, created for the film, that depict one young woman’s journey towards understanding her memories, each one with its own stop motion video.

When did you become interested in art & film?

In Brazil, I came across a book at home on figure drawing when I was about 11 years old. I think it was a gift to my parents. I took it to my room and copied all the faces, hands, and figures. It just clicked for me, it was a language that seemed familiar and made sense.

My father saw my drawings and thought maybe I had a knack for art and took me to meet a Brazilian painter Roberto D’Oliveira, who ran a studio-atelier. Learning to draw in his studio was my first introduction to a professional art setting, with northern lights, the smell of kneaded erasers, the feel of sharpening pencils with a blade instead of a pencil sharpener. I loved the whole atmosphere.

I did not imagine that I would become a professional artist. It never crossed my mind. I just thought of it as something I loved to do on my own time. I became more interested in film as a teenager. I love a good story and films are able to do that in a way that a still image cannot. I interned at a human rights documentary film company in college, intending to go straight into film. However, when I graduated [Tufts University with a BA and New York Academy of Art with an MFA], I still didn’t have a green card.

I had been offered an entry level job in a film company in LA but couldn’t take it. I moved back to New York. I was taking filmmaking classes at night and felt overwhelmed by the money needed to make a film, and the technical aspects of filmmaking.

I enrolled in a weekend painting class at the Art Students League and had a moment of realization in front of the canvas, that I could be the “director” of my own images much more effectively and immediately with paints and canvas, than the years it would take me to work my way up to making my own film.

What inspired you to get into Art & FIlm?

I found my way back into film through a series of oversized drawings I did in 2001 called “Close-Ups,” exploring the power of the movie close up, but rendered by hand. Movie images shaped the way I see the world, and I wanted to talk about that in my art.

In 2007, after my first child was born, I became interested in the subject of memory. When you have a child, you want to be able to pass down memories of your own childhood to them. I became frustrated when I realized that I had very few memories that I could put into words of my first 10 years in Hong Kong. I made a series of drawings called “Borrowed Memory” trying to fill up my empty “memory bank,” to see if I could use snapshots of Hong Kong from the 1970s to create the visual world that I lacked. It worked.

It was the subject of memory that ultimately brought me back to wanting to make a film. I had done two series of paintings exploring memory by looking at stills from the movies Ordinary People, The King’s Speech, and the HBO series “In Treatment,” and how the directors used light and the actors’ body language to convey the process of remembering.

In order to really explore memory, I needed to make images move and time pass.

How long did it take to put together ‘See Memory’?

It took me three years from start to finish. After I shot the footage, I really had no idea where I was going with it. I shot scenes with two actors — one playing a young woman who is troubled by her memories and on her way to therapy and the other, the therapist.

I was thinking of the movie Ordinary People and wanted to use the arc from that film which portrays a boy who is alone with memories that haunt him, unable to connect with others. Through his gradual connecting with a therapist and having a witness to his story, he is transformed and is able to live with what had seemed unbearable.

It took me a while to figure out that I would tell the story in paintings, how to shoot stop-motion animation, and how to make things move. The picture was locked after two years, but it took me another year to incorporate the interviews I had done with neuroscientists and psychiatrists and to figure out music and sound.

10,000 stills is a lot! Why so many?

Well, a live action film uses 24 frames per second. So, thousands of still images go into the making of any film. We just perceive the still images as moving because at a certain rate our eye perceives stills in sequence as motion. The difference here is that I made each image and each change by hand, in paint. In order for the eye to perceive the paintings as moving, those stills need to move fast and there needs to be a lot of them!

Describe the science of memory.

I had had the idea that memories are an accurate record of the past that can be put into words. What I learned in my interview with neuroscientist Daniela Schiller at Mount Sinai, is that memory does not have to be explicit, it can be a feeling that washes over you or a mood that seems familiar.

Even our behavior is memory, the way we act and react to things tells us about our past. I was also stunned to learn that a memory is malleable, subject to change each time it is recalled. In fact, the more times a memory is recalled, the more likely it is to have changed, like a game of telephone.

How did you get into stop motion film? It’s a very specific niche.

It was the way for me to bring together the things that I love: storytelling, film, and painting. As a painter, moving into film, live action moved too quickly for me. I was missing the joy of creating each image myself, by hand. I needed to slow the process down, to make each image appear gradually, building it stroke by stroke. That way, I could watch each scene take shape and make decisions about what would happen next while I was painting. The pace of the evolving images needed to match the pace at which I think, which is not knowing the way things should be from the start, but through a gradual feeling my way towards something.

Do your paintings reflect personal memories?

The paintings for “See Memory” started out as depictions of the story that I shot, but imagery such as horses appearing inside a room, or a hot air balloon appearing in the sky and turning into a boat are me free associating as I paint, so I suppose those are deeply personal as they arise from my subconscious.

The story itself reflects an amalgamation of personal experiences I’ve had that have led me to my believing strongly that it is only through the sharing of our life stories and connecting with others can we be freed from memories that haunt us.

What would you say is your most precious memory?

Nothing brings me more joy than looking at photos and videos of my kids when they were really little, hearing the sound of their voices and the funny things they said and did. As to a precious memory, any memory I have of being with my brother and sister as young kids in Hong Kong together is truly precious to me.

The exhibit runs now through Saturday, July 28, open to the public and on view every day from 10 AM to 5 PM by appointment through Iron Gate East at 512-773-5994 or email Kelcey Edwards at kelcey.edwards@irongateeast.com. The Spur is located at 280 Elm Street in Southampton. Visit www.vivianesilvera.com to learn more about Silvera.

@NikkiOnTheDaily

nicole@indyeastend.com