Spalding Gray Honored with Plaque at Former Sag Harbor Home

A plaque has been placed on Spalding Gray’s Sag Harbor home to designate it a literary landmark and to honor the remarkable contribution this man made in creating a new literary genre during his lifetime. Gray died by suicide in 2004. He was 62.

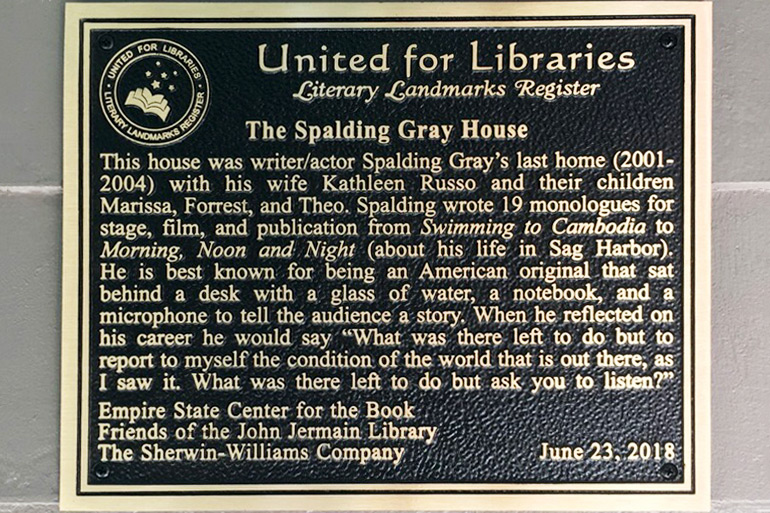

The plaque reads as follows:

United for Libraries

Literary Landmarks Register

THE SPALDING GRAY HOUSE

This house was writer actor Spalding Gray’s last home (2001–2004) with his wife Kathleen Russo and their children Marissa, Forest and Theo. Spalding wrote 19 monologues for stage, film, and publication from Swimming to Cambodia to Morning, Noon and Night (about his life in Sag Harbor). He is best known for being an American original that sat behind a desk with a glass of water, a notebook and a microphone to tell the audience a story.

When he reflected on his career he would say “What was there left to do but to report to myself the condition of the world that is out there, as I saw it. What was there left to do but ask you to listen?”

I was a great fan of Spalding’s. His Swimming to Cambodia monologue became a national event. He sat at a table, with a map of Cambodia behind him, with a pointer, some notes and he basically performed a breathtaking outpouring of his most personal feelings, sometimes whispered, sometimes shouted, always as a funny description of the craziness of the making of this movie he had been sent to Cambodia to have a small part in, about how his girlfriend didn’t want him to go, about how she did want him to go, about how he almost drowned, about bullets and explosions going on all around him.

I attended a performance of his next monologue, Monster in a Box, which took place under a tent on the lawn of what was then the Parrish Art Museum. There was an overflow crowd of hundreds of people. I stood in the back. He sat with his microphone in a chair at the front of the lawn and patted a box, which, if it actually had a novel in it, it would have been over a thousand pages.

From time to time he threatened to read from it, but when the time came, he would digress into another aspect of the experience of writing. There was always something. Friends, agents, distractions. At one point he claimed he had burned the manuscript but now had rewritten it. You could have heard a pin drop. Here he was, cynical, funny, puckish and mercurial—a classical WASP New Englander gone haywire. It was nice to know someone such as he could emerge from this community.

This was in 1987. People have done this since. David Sedaris is perhaps the best proponent of it today. But it is fair to say that Spalding started it. Today the radio waves are filled every weekend with people telling stories about themselves on The Moth, The New Yorker Radio Hour and at Symphony Space.

Authors speak at the Bridgehampton library every Friday afternoon during the summer about their work and lives. And Dan’s Papers runs a literary contest where writers enter nonfiction essays from 600 to 1,500 words that are true stories about themselves and others.

The winning entry this year will be announced at a ceremony at the John Drew Theater on Thursday, August 23 at 4 p.m. It is read aloud to the audience at the end by a prominent actor or actress. We’ve been doing this since 2012, and readers have included Pia Lindstrom, Mercedes Ruehl, Melissa Leo and Dick Cavett.

I once interviewed Spalding for Dan’s Papers, and he invited me over to his house to do it. He gave me a tour of the house. It was, I think, the first nice house he’d ever owned, and he was all excited about being in this lovely small town. Everybody knows everybody, he told me. I love Sag Harbor. And look outside. It even has a white picket fence all around. It’s perfect.

On another occasion, Christie Brinkley was hoping to get the powers-that-be to close down the Millstone Nuclear Plant in Connecticut. When the wind came from the northeast, which it did sometimes, whatever got emitted from the plant would blanket the eastern end of Long Island, she opined.

She called friends, including Spalding, to get them to join a group she was forming to fight this. And she wanted Spalding and me to meet to go over things. When I called Spalding, he said he was going to Sagg Main beach with his family and I should meet him there. So that’s what I did.

He lay there in a bathing suit and, instead of getting up, lifted himself on one elbow.

“So Christie wants to do this thing and I’m telling you we ought to do it,” he said, which was as close as he got to an endorsement. “By the way, I love how you get the news first in your paper. We stayed at home all day while that guy let out the lions to eat all the deer in the Hamptons.”

He was referring to a hoax I had written that week. Herds of lions would end the deer problem. Just stay at home on that particular Monday. Was he fooling with me? Or did he believe it? I never knew.

In a car driving around Ireland in 2001, Spalding was in a terrible accident. His head was fractured and metal plates had to be inserted. He was never the same after that. He couldn’t do his monologues, couldn’t think right. I recall him standing alongside a door at a party at the Ross School unable to say much. You could see the scar where they’d operated on his head and he seemed disheveled and frightened. He appeared not to even know who he was.

In the winter of 2003-4 he climbed up atop the bridge linking Sag Harbor to North Haven and threatened to jump off and kill himself. People talked him down. A year later, he did kill himself. It is believed he jumped off the Staten Island Ferry and drowned. His body washed ashore weeks later.

Someone like that, unable to work anymore, must have been suffering so. I guess he just wanted his family and friends to remember him how he was.

His widow, Kathie Russo, arranged for a documentary to be made about her husband, using homemade movies and pieces of footage from his performances. Steven Soderbergh directed it. It’s called And Everything Is Going Fine and is available on demand.

About five years after Spalding died, my wife and I spent two weeks driving around Ireland, which is very beautiful. I thought of Spalding and decided to be extremely cautious when I drove there.

However, late in the day of my first day of driving, on narrow roads with right-hand-drive cars passing oncoming cars on the right and road instruction in Gaelic, I constantly had to battle driving out of the lane on the left, resulting in terrifying both myself and my wife. I ultimately clipped the mirror on a parked car, and so concluded it was too dangerous for me to do and as a result hired a driver to take us around for the whole rest of the trip.

By the way, Spalding’s house has been spruced up for the unveiling of the plaque. The paint company Sherwin-Williams, because of a Spalding Gray fan’s insistence (their dog was named Spalding Gray), had developed a new color called “Spalding Gray.” Spalding’s widow asked if the company would paint her house Spalding Gray in honor of him, and they did, without charge.

Many snippets of Spalding’s monologues can be viewed on YouTube. This is the Spalding we all knew and loved.

This is the third house on Long Island to be the recipient of a plaque about a famous literary figure having lived there. The other two are Walt Whitman’s birthplace in Huntington Station and the Southampton College windmill where Tennessee Williams lived and wrote during the summer of 1957. Perhaps another should be placed on the home where John Steinbeck wrote Travels with Charley and other pieces in the 1950s