Dreams, Myths, Experiences

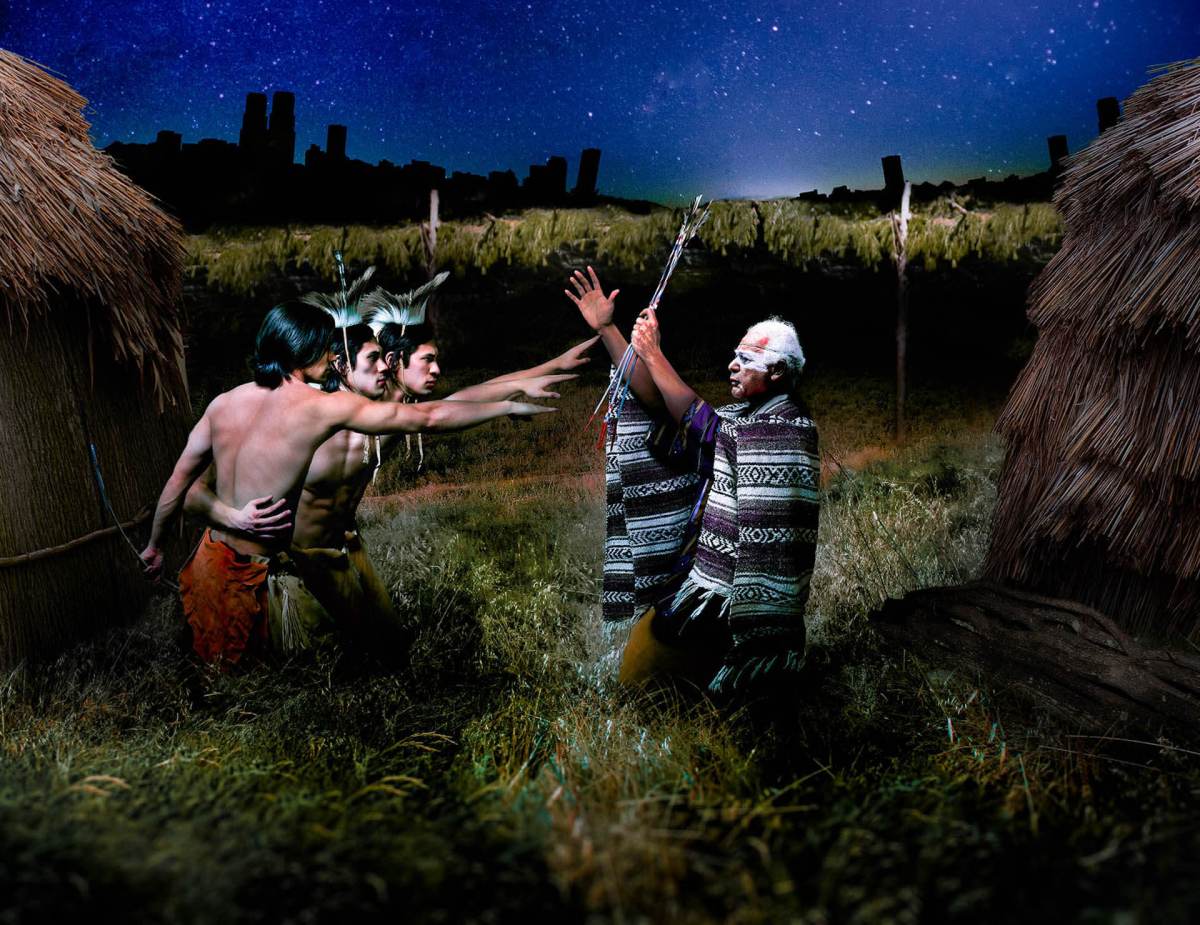

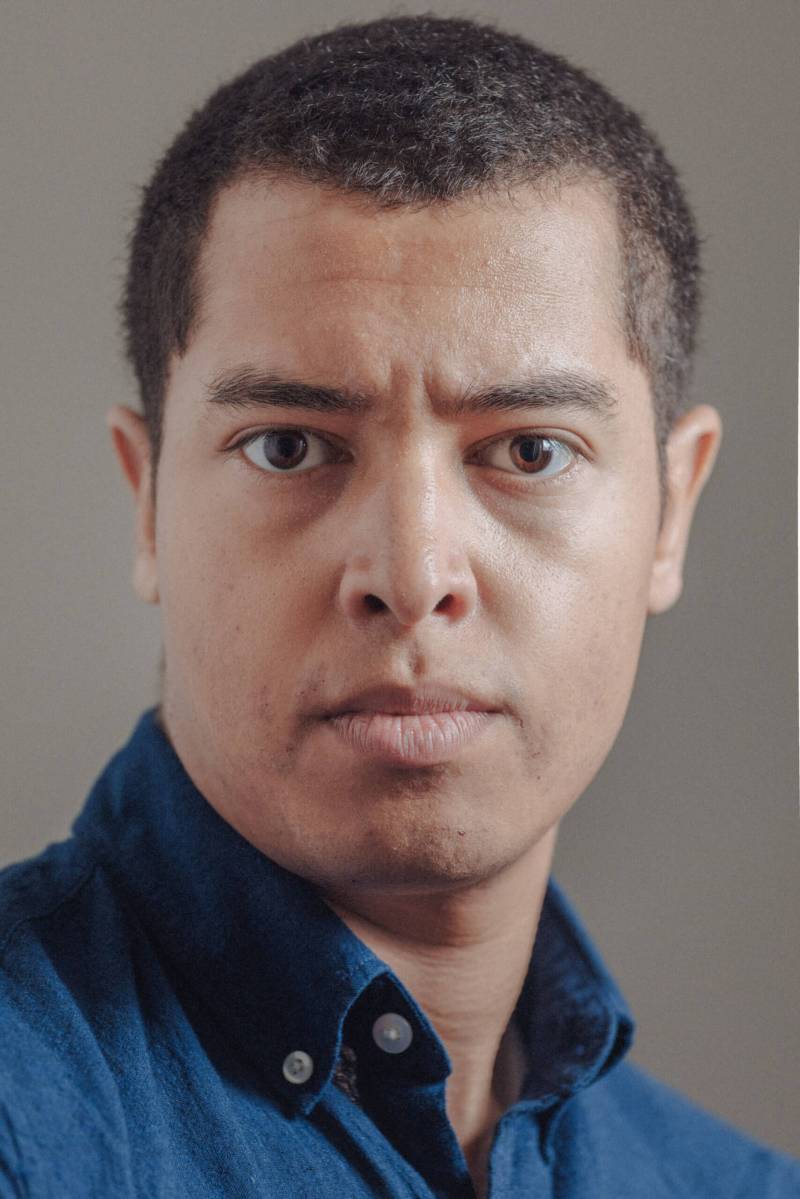

Parrish Art Museum presents the Parrish Road Show at the John Little Barn at Duck Creek Farm in East Hampton this Saturday, August 11, with an opening reception of fine art photographer Jeremy Dennis’s exhibit “Stories — Dreams, Myths, and Experiences.”

As a Native American growing up on the Shinnecock Reservation, Dennis will feature seven images from his project that depict indigenous stories and supernatural images. Starting at 3 PM and going until 5 PM, will be an opening blessing and welcoming song by Shinnecock tribal member Shane Weeks and an introduction to the work by Dennis and Parrish Curator Corinne Erni.

Describe what it was like to be raised on the Shinnecock Nation Reservation.

Growing up on the Shinnecock Indian Reservation was great. I was fortunate to be raised where my ancestors have lived for thousands of years!

As an adult, I’ve become more aware of how unique our reservation is in regard to our local history and geography. Much of the unavoidable conversations we have with our neighbors still relates to remaining and aiming to be acknowledged for our presence and contributions.

What are some of the indigenous stories you’ve recreated?

For the exhibition, Corinne Erni, Curator of Special Projects at the Parrish Art Museum, and I have chosen seven stories out of about 80 from the project series to represent in the show. They are titled Chokanipok, Ghost of the White Deer, The Oath, The Interment of Pogattacut, The Legend of O-Na-Wut-A-Qut-O, The Moon Person, and The Stone Coats. The images span 2014 to 2017 and deal with many themes.

Does one image in particular resonate with you most?

The image I am most happy with is The Interment of Pogattacut, based on a local historic landmark between East Hampton and Sag Harbor on Route 114. The landmark is called “Sachem’s Hole,” also known as Buc-usk–kil, or “resting place.” It’s the site where the late Manhasset Sachem Poggatticut was laid upon the ground as he was being brought from Shelter Island to Montauk for interment in 1651.

From that point on, the area was always kept clear of leaves and debris by local tribal members traveling that route until the site was eventually destroyed by Route 114.

A historical marker erected in 1935 by the State Education Department stands on that spot today. I think it’s so great when art, life, and storytelling can easily be so accessible and relevant.

So many of us are ‘American,’ by way of immigration. How do the terms ‘American’ and ‘Native American’ differ in your mind? What does being American mean to you?

More and more, we are becoming aware of the complexity of Native American culture and history and a diverse group of unique and sovereign nations who each have their own language, history, and relationship with the United States at a government-to-government level. Because of this, the hope is that, in the future, the nations will one day be addressed or recognized by their unique names. For example, I could say, “Hello, my name is Jeremy and I am Shinnecock,” with the hope that being Native American or indigenous is inherent in the name.

In regard to American versus Native American, I think that many people describe themselves as both American and Native when they are from a certain area or town regardless of their background. But for indigenous people that can often contribute to indigenous erasure — or the new idea that “We are all Native American because we are born here.”

What issues do you feel plague Native American communities most in today’s contemporary culture?

For many Native American communities, the number one priority is tribal sovereignty and economic self-dependence. Between the contact-period in America’s history and today, Native people have been removed from the most valuable resource: land.

Looking at this issue on a local level, real estate is one of the most valuable yet sparse assets. For Shinnecock and I’m sure for other tribal nations, there has always been a conflict between the use of land, selling and gaining land, and who gets to live on the little land that remains.

How do we bridge that gap?

There have been several efforts to regain land that was taken illegitimately, but there has been a resistance to reconcile after so many decades. That struggle is still being pursued as often as the courts will hear us, but we also seek other modes of economic development.

Are all of your subjects in your Parrish exhibit of Native American descent?

It is half and half Native descent and volunteer models who participated in the project. For a long time, I debated working with non-native models, but I was convinced to do that to while reading Thomas King’s The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America.

In his book, King quotes Cree playwright Tomson Highway who answered the same question with this statement: “To insist that Native parts go only to Native actors was a good way to silence Native drama and starve Native playwrights, since there were not enough Native actors to mount plays in various cities around North America at the same time.”

I think the issue is heightened when it is at the Hollywood or Broadway level for example; many more people will see the erasure, the opportunity to pay large amounts to talented Native actors and models is lost.

What is your creative process like?

I always begin with an influential text. Sometimes that is working directly from an oral story, a description of a dream; or on the other end, trying to work with theory and philosophy in text and trying to represent that in a visual motif.

As I read, I always have an image of a scene in my mind. That vision is what I try to depict in each image — attempting to recreate it as truly as possible, which often requires assets added later on, during post-production.

What do you hope the public walks away with after seeing your exhibit?

Most of all, I want the public to see us (Shinnecock) as a contemporary and complex people and culture. The cultural production behind the photographs and the fact that the Parrish Art Museum has made this exhibit possible is a glimpse at a hopeful future of filling gaps and celebrating differences and similarities between my tribal community and our neighbors.

What’s the message you’re trying to convey most?

Each piece in the show addresses a different message, and the general motivation behind the project has changed throughout producing the work, from 2012 to 2018. But the common thread is that we have an essential connection to our environment as a place of origin and as an ingredient to our survival.

Traditional oral stories and the sacred sites where they take place offer a compelling reason to preserve the environment despite the scientific revolutions that convince us that mythology no longer has any practicality and has made us all skeptical. While working on this series, I’ve been working out ways to elevate myth and storytelling to the same relevance and importance.

The John Little Barn at Duck Creek Farm is located at 127 Squaw Road in East Hampton. The event is on view through September 3, and is free and open to the public. Hours are Friday through Sunday, 12 to 4 PM, or by appointment. Call 631-283-2118 ext 140.