Guarding Against A Deadly Foe

The illicit synthetic drug mixing agent fentanyl is light, comes in small packages, and is rarely seen in its purest, deadliest form.

A useful drug physicians use in surgeries and for long-term pain management, fentanyl has hit the streets and is being mixed with opiates like heroin and then sold to addicts to intensify their high. But even a spec of its purest form can kill someone, and for first responders like police officers — the people who are most likely to come in contact with the deadly substance — there is an added danger of exposure when they are on the scene of a drug overdose or arrest.

They could enter a home or undertake a traffic stop, where sellers or users have the drug out in the open, uncovered, and all it takes is a stiff wind to blow the substance about a room or car. The drug could also be hidden somewhere on a suspect, and then ripped open by accident during a search of a pocket or a shoe. Either way, exposure through the air can penetrate vulnerable mucus membranes such as the eyes, nose, or mouth. The drug can also be absorbed through the skin.

“Because we are so concerned about the fentanyl situation, we decided that we have to protect the officers,” said Southampton Town Police Lieutenant Susan Ralph, who trains the department’s officers against exposure, as well as on the administration of naloxone, the antidote to opiates which can be used to revive people who overdose.

Police Chief Steven Skrynecki voiced concerns about fentanyl after three people overdosed at the same house in the Northampton area last month. Two people were revived in the incident; however, the third did not survive. Skrynecki requested a rush on toxicology reports from drug evidence collected at the scene in hopes of putting the dealer out of business.

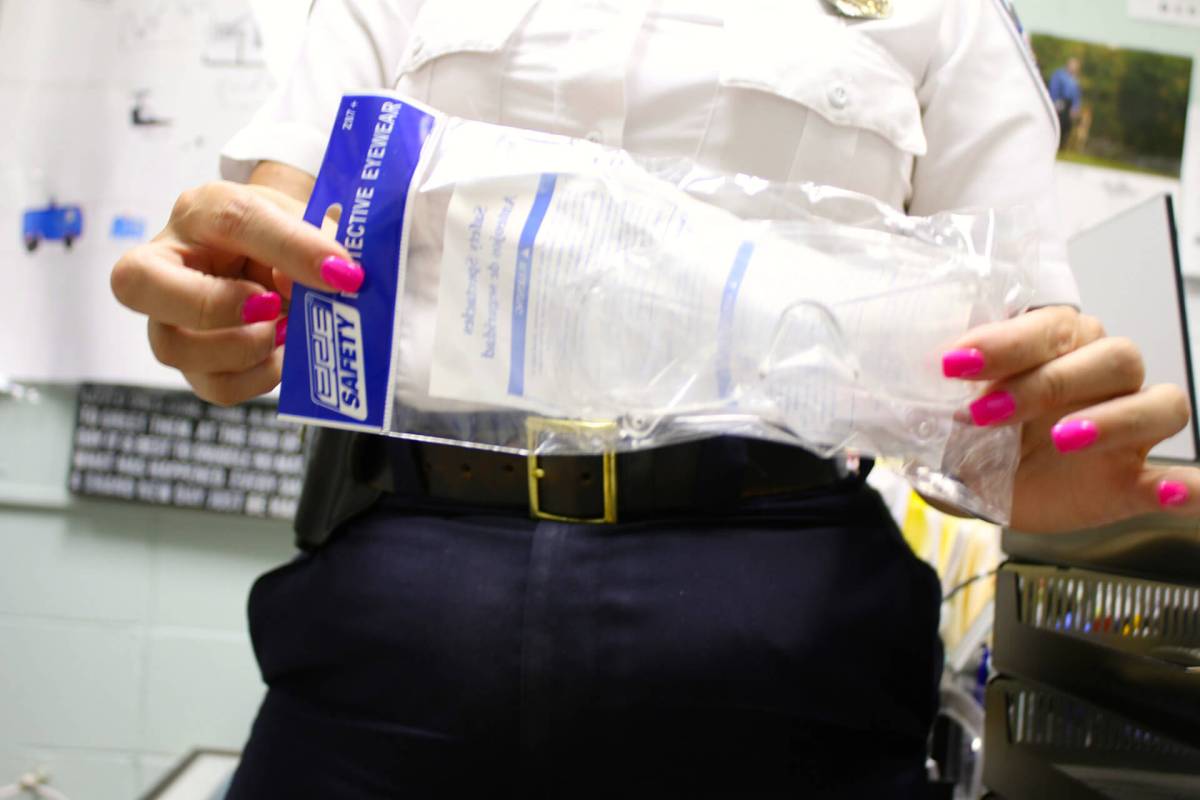

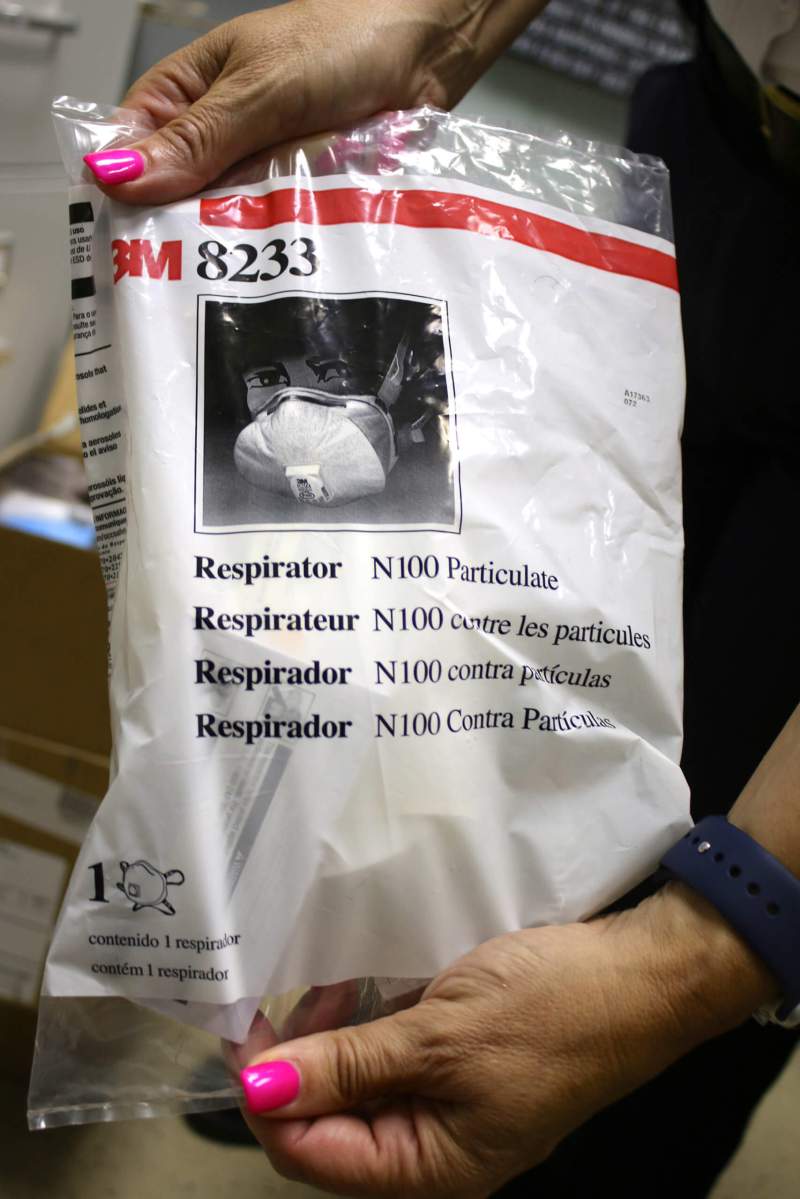

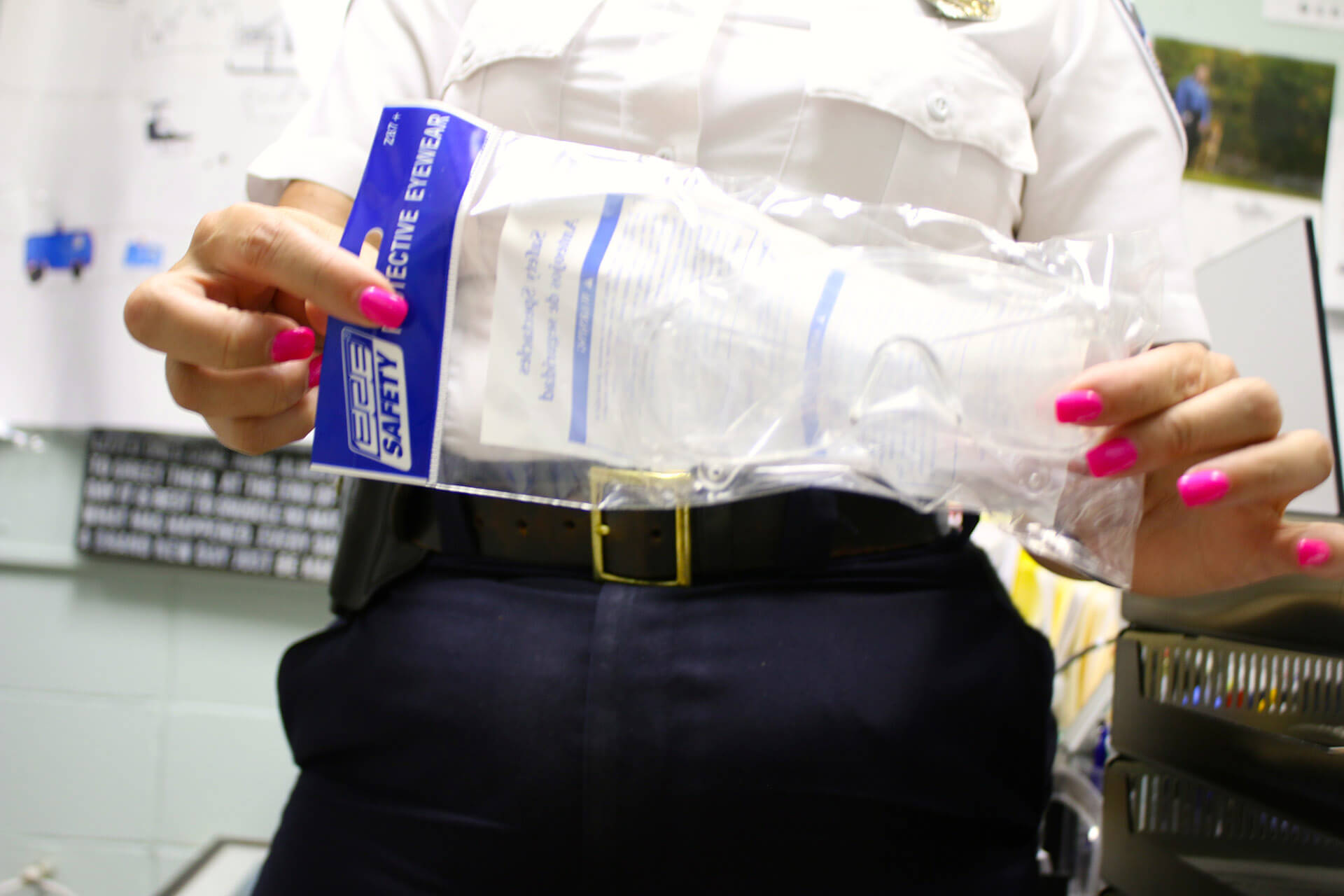

The department has outfitted each police car with kits, priced at roughly $40, to guard against exposure to the drug. The kits contain plastic glasses to protect the eyes, a pair of paper booties to pull over shoes, a filtered mask to remove any dangerous particles from reaching the nose, and a pair of black rubber surgical gloves for the hands.

“They’re a little bit heavier and there are really no breaks in them for anything to soak through,” said Ralph as she pulled one of the gloves over her hand and stretched it out to demonstrate its strength and flexibility.

The kits are generally used whenever officers respond to a drug overdose. Officers responded to 11 of those cases up until June 27, not counting fatalities, where there was the option of using the kit, Ralph said. However, there is no way of gauging how many of the kits have been used, she said, because officers do not always report to her when they have used them. “Again, when you are getting that call for that aided case, these officers are running in. They are going in to save that life,” she said.

The department has also issued special hazmat suits to guard against exposure to fentanyl, which are only used in extreme cases where there would be a high likelihood of exposure. The suits could also be upgraded to a “level A suit,” fully encapsulating a person’s body to enter into an area where the drugs might be produced, she said.

In an incident this year, two officers from the department were exposed during a traffic stop in which the suspect began throwing items out of a car. The substance then blew back into the officers’ faces, and they experienced dizziness and lightheadedness, requiring them to be checked out at a local hospital.

“There was a case upstate where an officer was dealing with an arrestee, and another officer said, ‘Hey, you have some powder on your shirt,’ and brushed his shirt,” Ralph said. The seemingly innocuous action caused the man to lose consciousness. “He went down.”

Use of the kits is left to the discretion of the officer and the situation, according to Ralph. “Obviously, the department recommends it anytime you are going into a situation, whether you are searching a vehicle after you make an arrest, and you know there is narcotics, or the person tells you there is narcotics in the car,” she said. “You don’t want [the officers] being exposed to it because, again, the first responder needs another first responder. So, they are trying to save someone and now they need to be saved also, that doesn’t bode well for us.”