The Hurricane of 1938, Part I: The Barometer, a Prelude

This is part one of a three-part series Dan Rattiner wrote for the 80th anniversary of the devastating Hurricane of 1938 in our September 21, 2018 issue. It originally appeared as one long-form story.

Read Part II: The Path, Arrival

Read Part III: The Aftermath, an Epilogue

THE BAROMETER

On the warm morning of Wednesday, September 21, 1938, the telephone rang at the oceanfront home of Trevor J. Davis, on Dune Road, Westhampton Beach.

“Hello, Mr. Davis?”

“Yes, this is he.” Davis replied, rubbing the sleep out of his eyes.

“Mr. Davis, this is the post office. We have a C.O.D. package for you. It’s 11 dollars and 55 cents.”

“Is it from Chicago?”

“Yes. Sears Roebuck, in Chicago. It’s about a foot square.”

“Oh, well, that’s my new barometer. I’ll be down to pick it up after breakfast.”

“We’ll be open all day. Goodbye, Mr. Davis.”

“Goodbye.”

Trevor thought for a minute how nice it was that old Mr. Baker would take the trouble to call him that a package had arrived C.O.D. But then he remembered that he had told Mr. Baker he was getting a barometer, and Mr. Baker said he’d be interested in seeing it. Trevor decided he’d probably open the package right there at the post office and they’d have a look at it together. No reason why not.

Trevor changed from his silk bathrobe into his summer whites, and went downstairs to the kitchen. He was alone this weekend, having left his servants in the city with his wife and children, and he was roughing it. Camping out in his very own summer home.

It was such a lovely morning, with the ocean waves rumbling in right outside his window, that nearly two hours went by before pulled his Packard up to the post office on Main Street. A light breeze had sprung up and he noticed that the sky was getting quite dark. There was also an almost sticky warmth to the air. Setting his brake, Trevor hopped down to the street and walked around the car into the post office and up to the counter.

“Here ’tis,” Mr. Baker said, setting the package out almost before the bell had stopped jangling on the door. “Got here in just five days. Pretty good time from Chicago, if you ask me.”

Trevor gave Mr. Baker a 10 and a 5, and Mr. Baker gave him back the change.

“I think I’ll open it and have a look,” Trevor said, with just the trace of a smile. “Certainly wouldn’t want it if it were defective.”

“Certainly not,” Mr. Baker said, leaving off everything he was doing and giving the package his full attention.

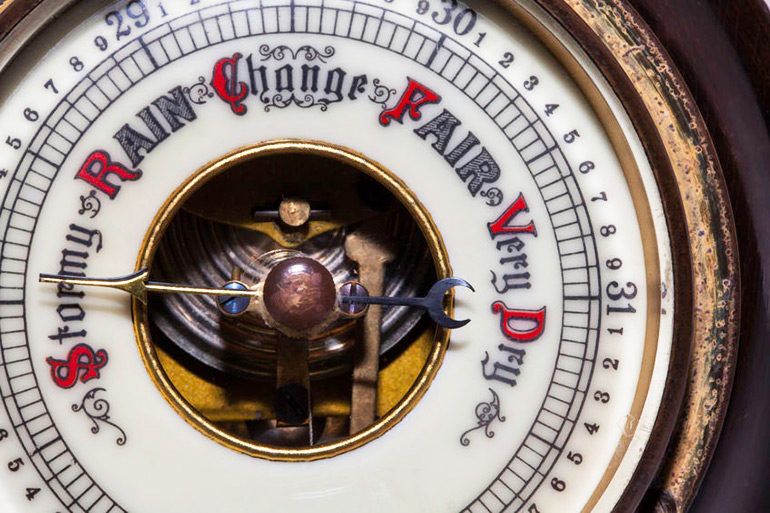

“Now, you were asking me how one of these things works,” Trevor said as he undid the string. “Well, what the barometer does is measure the pressure in the air. Generally speaking, when the pressure is high, the weather is good, and when it is low, the weather is not good.”

“What’s the pressure on an average day?”

“Oh, about 30. I’ve seen it rise as high as 31, and do you remember that storm we had last year? The pressure dropped to almost 29. Or so they said over the radio.”

Trevor undid the last of the wrapping and took out the barometer. It was in a beautiful mahogany case and had a shiny glass frontispiece through which you could see the dial of the instrument.

It read 28.3.

“This is strange,” Trevor said, looking at the peculiar reading. “Maybe it is stuck.”

He tapped it a couple of times with the palm of his hand. But the dial stayed resolutely where it was.

“What’s the matter?” Mr. Baker asked.

“Well, this barometer reads 28.3. And there’s no possible way it could read that low. There must be something wrong with it.”

Mr. Baker began picking up the wrapping and the box, which it came in. He was trying to be helpful but he had no idea what he was looking for. He just shuffled things around.

“Maybe there’s a piece missing?” he said.

“No, it’s all of a piece. I think we just got a bum barometer. It’s not like Sears and Roebuck, but I guess it happens to the best of us.”

“You want to send it back? You can, you know. You don’t have to accept a package C.O.D.”

“Well, I guess that would be the best thing to do. Sure is a shame, though.”

Trevor and Mr. Baker got everything together and silently began repacking the package. Before they sealed it, Trevor got a paper and a pencil and wrote out a note INSTRUMENT DEFECTIVE, PLEASE SEND ANOTHER, and enclosed it in the box. Then they closed it up, sealed it, and Mr. Baker returned Trevor’s money.

“You coming out the next few weekends?” Mr. Baker asked.

“I expect so.”

“Well, I’ll call you again when the next one arrives. You could figure two weeks or three.”

“We’ll be coming out right through the end of October.”

“I’ll call you Wednesdays.”

Trevor picked up the rest of his mail, which consisted of a single bill from the Westhampton Liquor Store, and opened the door to walk out to his car. It was quite windy now, and a light, warm rain was falling nearly sideways, rustling the leaves in the trees. Trevor put his hand on the brim of his tennis hat, ducked his head into his shoulders and ran the 20 feet to his car, laughing.

This was a rough kind of weather that he liked. Weather that came down from the heavens, that let you know it was there. It was, in fact, the reason he’d purchased the summer house on the beach 10 years before, and the reason he’d purchased the barometer.

Trevor started the engine to his car and drove down Main Street. Twigs and small branches were flying across the road, and a few merchants could be seen rolling up their awnings. Turning left on Stephen’s Lane, Trevor was surprised to see that a good-sized tree had fallen down on someone’s lawn. There was also a deck chair blowing across the road in front of him. Trevor slowed down to let the deck chair pass, and rolled up his window to stop the wind from whistling. He turned left again onto Jessup Street. The wind was stronger and the Packard was rocking from side to side.

And then Trevor looked up and could hardly believe his eyes. The water in the bay had risen so high it was washing across the Jessup’s Neck Bridge in front of him. He would be unable to cross the bridge to get to the Dune Road beyond. Trevor stopped his car and stared. His jaw dropped.

Across the bridge, on Dune Road, where there had been a good two dozen houses when he left this morning, including his own, there was nothing. Trevor rubbed his eyes. There was no fog. He could see the sight crystal clear. A few roofs, a door, a window jutting up here and there. The sea had inundated Dune Road. It had met the bay. There was nothing for him to drive home to.

Trevor Davis, still in his tennis whites, turned the Packard around and drove it quickly through the mounting storm to the Howell House Hotel. It was the strongest structure he could think of. And it was already filling with refugees.

PRELUDE

It is impossible today, looking back at the incredible catastrophe that was the Hurricane of ’38, to imagine how unprepared the eastern end of Long Island really was back then. But it was the case. As a natural catastrophe rivaling a natural calamity, larger than any that had ever struck the world in a decade, built in its ferocious intensity in the North Atlantic, the people of the East End woke on the morning of Wednesday, September 21, 1938 as if it were just another day.

In Montauk, the 26 fishing families that lived in the picturesque cottages on the arc of Fort Pond Bay awakened to a peaceful day. As there had been a possible storm predicted the night before, a storm that apparently was not going to materialize, the fishermen as a group chose not to go out, but instead to spend the day mending their nets and enjoying their families. By nine o’clock in the morning, the smell of coffee pervaded the air, wafting down the single dirt road of the village, past the schoolhouse, the post office and the Union News Restaurant building to the small fleet tied to the docks.

In the Hamptons, time, then as it is now, was measured in weeks. This was approaching the third weekend after Labor Day, and, although there were fewer visitors out than there had been the week before, there was still a goodly number of summer people. Most had driven out from the city the night before—a four-hour drive, down the Montauk Highway to their summer homes—and most had come with their servants to get on with the bittersweet occupation of folding and packing and closing down for the winter. In the Hamptons, this was the heyday of the “cottages.”

There were nearly 1,000 of these magnificent summer homes, lining the beach from Amagansett to Dune Road, Westhampton Beach, each with 20 or 30 rooms, and each habitable only 15 or 20 weeks of the year, due to a complete absence of any heating system.

The economy of the Hamptons had, in fact, been built on the popularity of the cottages, occupied as they were by the cream of New York society, with their attendant lawn parties, servants, clubs, shops and stables. And so, as that fateful Wednesday dawned, few persons imagined that the day would be anything other than expected—a day to buy some furniture covers, go out to the beach, if the weather was willing, perhaps take the kids to the matinee at the Edwards Theatre in East Hampton.

Up on the North Fork, the day also began as any other. In Southold, the farmers were busy getting the potatoes out of the ground. At Greenport, dozens of tourists “just happened” to walk down the pier to get a look at the beautiful Vanderbilt yacht tied up there. The boat was on a cruise and the Vanderbilts were in residence. There was a beautiful wind indicator mounted on a porthole which could measure winds up to 150 mph. Out at Orient, at 8:30 that Wednesday morning, the first load of cars made their way aboard the ferry for the cross-sound trip to New London.

Also that peaceful Wednesday morning, Mr. and Mrs. Phineas J. Clipp arrived at their summer home in Georgica, East Hampton. Mr. and Mrs. Clipp pulled up that morning in their dusty, chauffeur-driven Lincoln, and what was unusual about their arrival was that they had left East Hampton for their winter home in Palm Beach two weeks earlier. Workmen were scheduled to board up the East Hampton home for the winter in just a week or two.

Mr. Clipp stepped out of the car and stretched his arms as far as they would go, smoothing the wrinkles in his blue blazer. He walked around to the other side of the car and let his wife out. It was good to be back in East Hampton. The leaves were still on the trees, and, except for the pervading sense of peace and quiet, it might as well have been summer.

The chauffeur stepped out of the car, and he stretched too. It had been an exhausting drive. They had left Palm Beach Friday—they told their friends there that something had come up unexpectedly—and they had driven for five straight days, spending nearly 12 hours each day cooped up inside the Lincoln, to get back to their summer place in Georgica.

The chauffeur walked around to the trunk and began to unload the bags. There had not been very much packed, really. Just enough to last for 10 days, by which time a bad hurricane, which was expected to strike the coast of Florida, would have passed and it would be safe to drive back to Palm Beach.