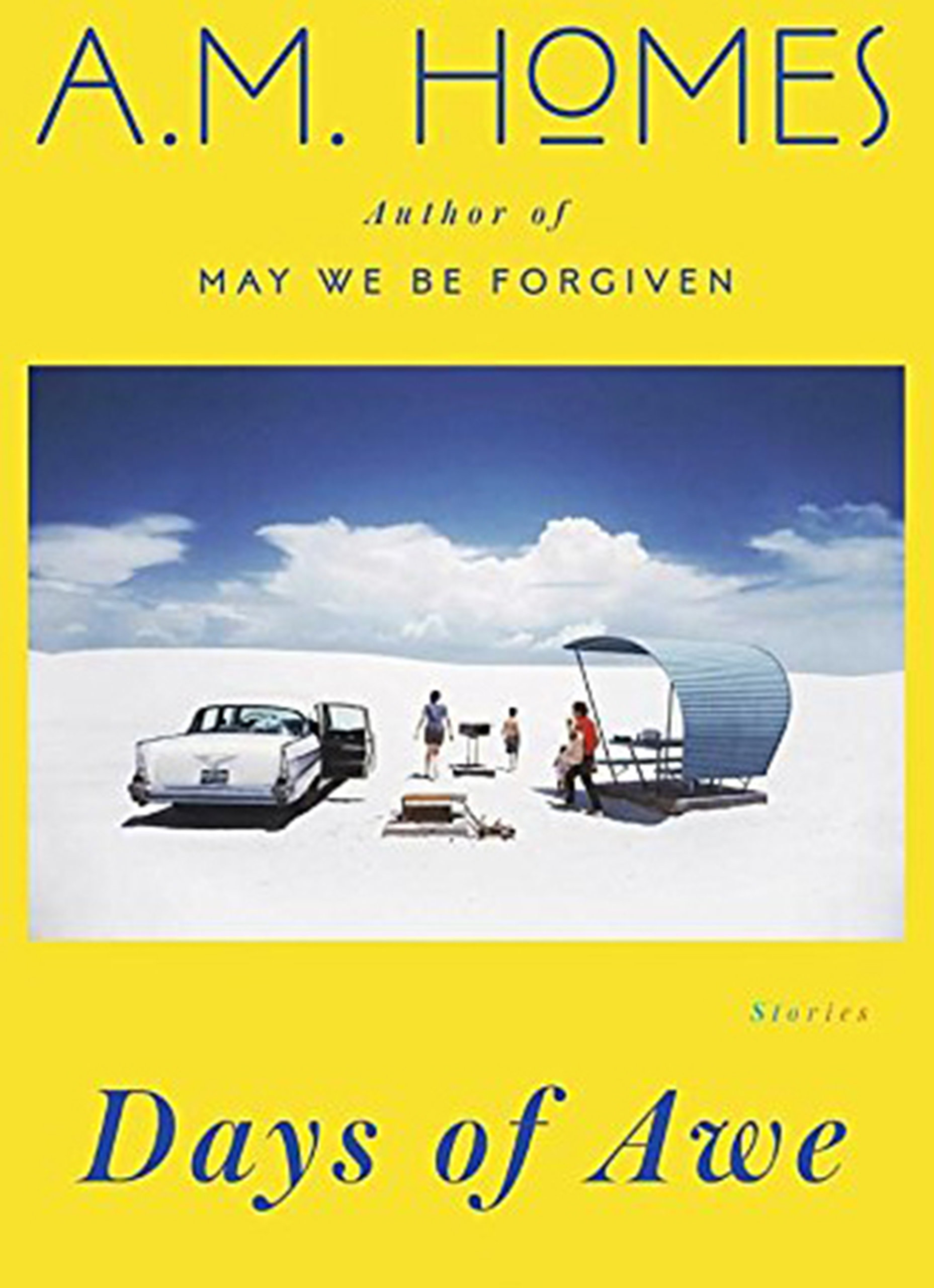

Days of Awe by A.M. Homes

Dialogue is reminiscent of contemporary playwrights

Arguably, the most remarkable feature of A.M. Homes’s fine fiction is dialogue. Conversations and interior monologues just seem to start, plunge in, in medias res, as though the reader was belatedly made privy to a bizarre exchange that’s been proceeding like parallel tracks, each speaker intent on advancing his or her own obsession. If this stylistic mannerism — at times, sadly comic, at other times desperate and fearful — seems reminiscent of the seemingly discordant non-sequitur exchanges of some contemporary theatre, it’s no surprise.

The author has said in interviews that Harold Pinter and Arthur Miller have always been favorites, and that Edward Albee, who was a long-time friend and mentor, shared not only a love of the stage but the fact of being adopted (a motif that figures in Homes’s fiction).

Homes’s characters, needy in the extreme, lonely, confused, somewhat aware of their plight but reluctant to say so, align her perhaps with Sam Shepard as she explores the ambivalence of relationships, particularly among family and friends. But here’s a paradox: Though the prose invites reading aloud, the conversations say, “Read me.” And then re-read. Who’s talking? Does one character hear the other? How does the author so skillfully ease from satire to sympathy and pathos?

Although Homes has won awards for her novels, she is no stranger to story collections, or nonfiction or memoir, or film or TV, for that matter. Days of Awe comprises 12 stories, which range from close-to-the-bone realism to outrageous fantasy, as in “A Prize for Every Player,” where a family, contest-shopping fast in a mall store, winds up with a baby, discovered in the towel section, and the husband/father finds himself nominated for president.

Homes’s stories typically don’t get resolved, they just end. The best ones, though, haunt and impress — How did she get the brittle tensions so right, the observations so on-spot quirky? One troubled soul hears her therapist “cluck” and wonders: “Aren’t therapists trained not to cluck?” And from “Hello Everybody” — “‘You should be an actress,’ people used to tell Abigail. ‘You should be yourself,’ Cheryl says. ‘No idea how to do that,’ Abigail confesses.” In “Omega Point,” a man answers a stranger, a gas station attendant, who says he looks familiar, with: “People say I bear a striking resemblance, both physical and philosophical, to Voltaire . . .”

In the title story, “Days of Awe,” a “War Correspondent” and a “Transgressive Novelist,” he, newly returned from horror zones, she, an academic specializing in the Holocaust who’s in a lesbian relationship, meet up after years at a genocide conference and wind up wild in bed — “They finish coated in each other.” The story demonstrates Homes’s talent for description. Sentence rhythms swell with life, as the characters do not. “It is the season of bounty; the apple trees are heavy with fruit, the wild grass along the highway is high. Wind sweeps through the trees. Everything breathes deeply, nature’s end-of-the-summer sigh. In a couple of hours, a late-afternoon thunderstorm will sweep through, rinsing the air clean.”

The title, “Days of Awe” refers to the start of the High Holy Days in the Jewish calendar, one of several such ethnic allusions throughout (“The welcome lunch is served: cold salads like the sisterhood lunch after a bar mitzvah, a trio of scoops, egg salad, tuna salad, potato salad . . .”).

A man leaves his family to visit his dying mother in a nursing home in California: He’s always dreamed it’s the “most American place in America . . . In his imagination it is a place where the Old West meets Marilyn Monroe, where every street is decorated differently — he is conflating Disneyland with Hollywood and doesn’t even know it.” In “All Good Except or the Rain,” two spoiled rich LA women meet for the barest of lunches to tell each other semi-truths about their lives. They are interrupted by an attending waiter (hilarious) they hardly acknowledge and console themselves at the end with fattening pudding.

And then there is “The National Cage Bird Show,” striking for its profound oddity, clever page formatting and subtle compassion about a chat room for people who like (but who do not necessarily own) birds. The participants include a traumatized soldier writing from abroad and a lonely young girl in the city (slight shades of Salinger’s “For Esme With Love and Squalor”?) In interviews, Homes has said she hopes her stories are “food for thought but also food for the soul and mind.” They should also prove exemplary for established writers and wannabes.