Wilkes Takes Photography To New Heights

Famed photographer Stephen Wilkes has created “Day to Night” photographs of cities and natural habitats throughout the world. Perching himself atop a 50-foot viewing platform looking down, Wilkes remains a stationary observer for hours on end, gathering 1200 to 1500 images from dawn until dusk that will be combined into a single image.

Recently featured in National Geographic’s issue celebrating 100 years of State Parks in America, his work is being shown at the Tulla Booth Gallery in Sag Harbor through September 27.

How did you get into this form of photography? It seems to require a lot of patience.

It’s all the things I love about the medium of photography and that’s how it evolved. There’s the initial seed of an idea and then there’s the moment where something presents itself, and then there’s this intersection when you take the idea and create an execution where it comes to life. For me, the seed was in 1996 I was doing a photograph for Life Magazine on the Romeo & Juliet film, where they asked me to do a panoramic of the cast and crew, all in one photograph. I got there and the set was a square, so I’m trying to think how I can make it panoramic.

I remembered seeing a David Hockney collage of pictures and thought rather than shoot one picture, I could shoot 250 images. That’s what I started doing. I had the cast and crew all together, with Leonardo DiCaprio in the center of the picture with Claire Danes, and then the cast and crew behind them. I started on the far left and I began to slowly pan my camera and take pictures. As I photographed, there was this huge mirror in my view and in that mirror, Leo and Claire were reflecting. At that moment, I said, “Could you kiss for this one picture?” And they kissed.

Then I came back to New York and spent a week putting this together by hand. I just looked at it, dumbfounded, and saw the concept of changing time in a photograph kind of hit me. That stayed with me for 16 years until the advent of Photoshop. When I saw technology could do with Photoshop, suddenly that idea came back to the forefront.

How do you prepare for your shoots?

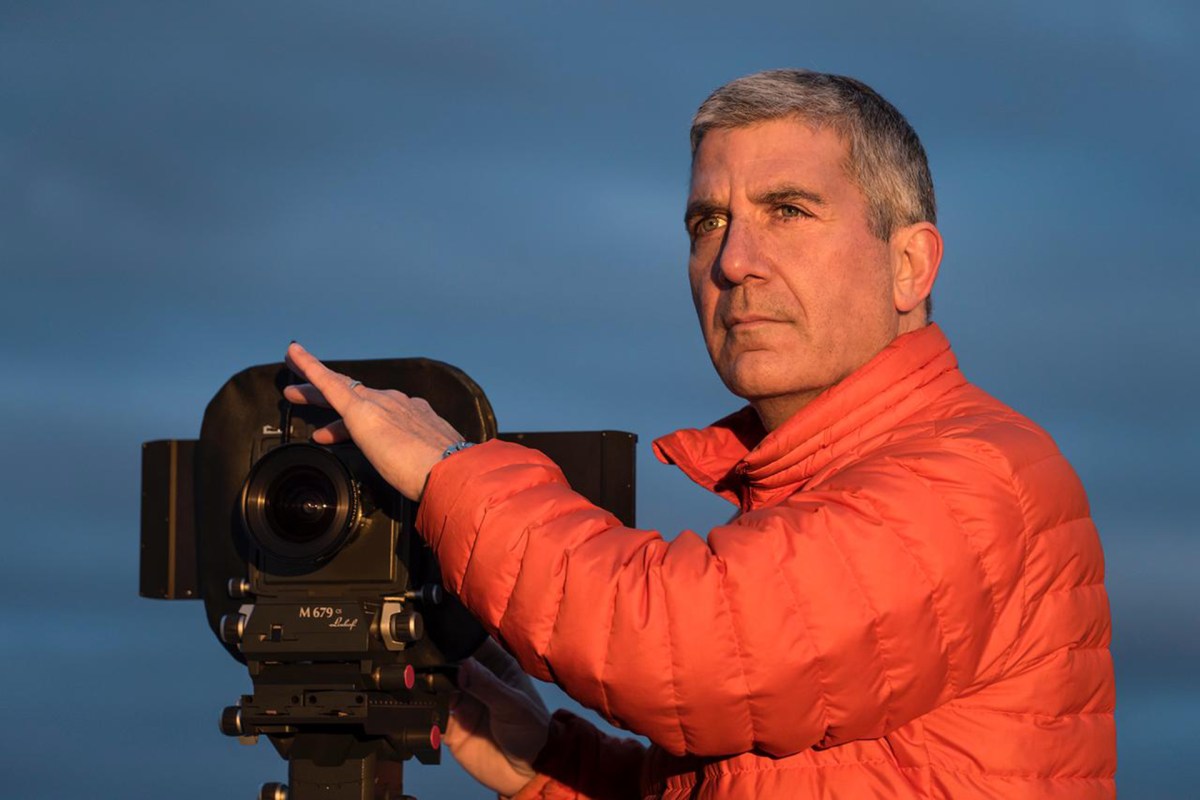

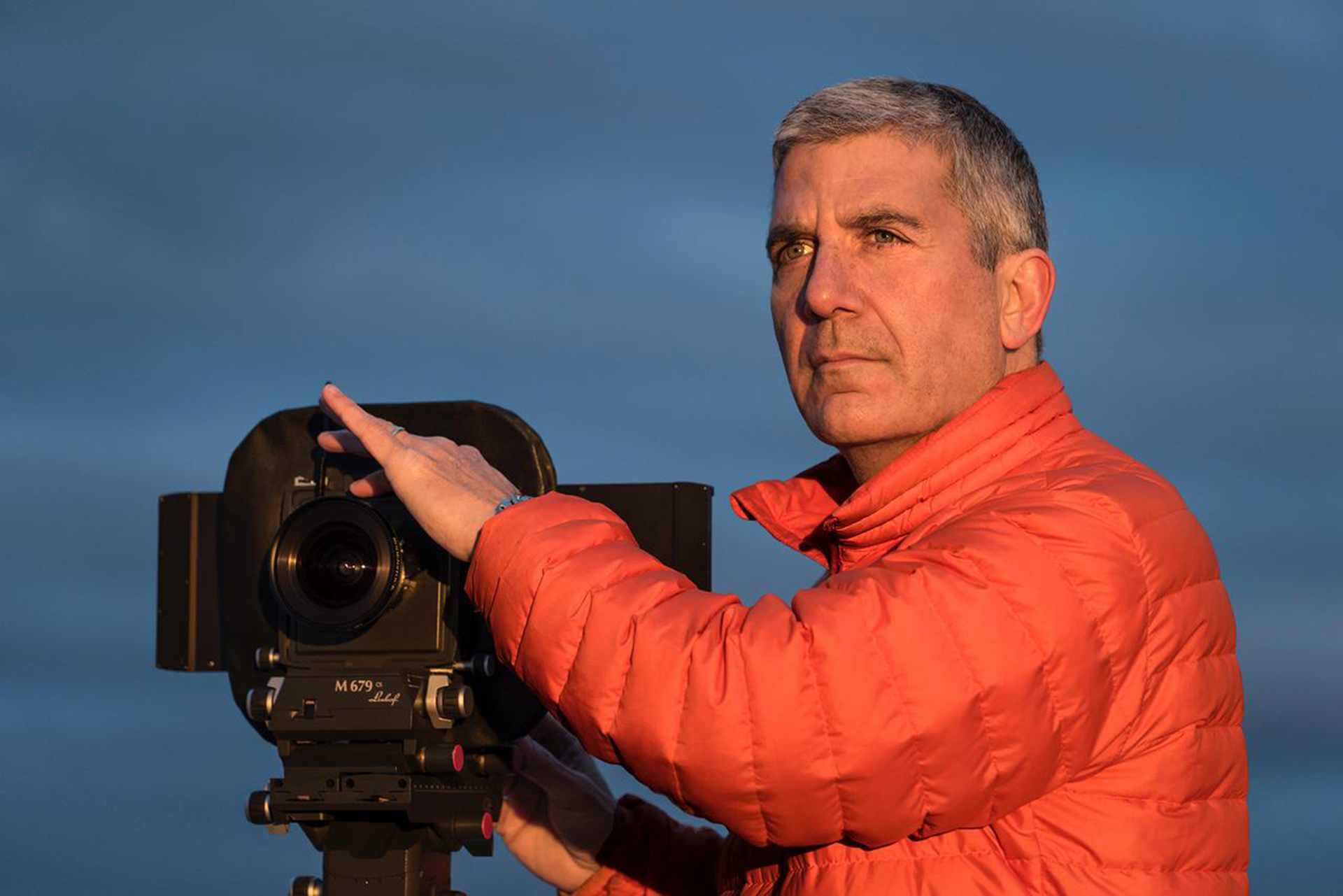

The machines I go with are 150 to 170 feet. I only go up about 50 feet in the air but there are so many variables with what could go wrong. If I get more than a 10-mph wind at night, I can’t shoot; I get too much vibration. I could have the most perfect day and then when the sun sets, gusts of wind change everything. So many factors have to come together to create these images. At the end of the day, hopefully I’ve done my homework and the weather cooperates. I like to create a positive energy around a photograph. That’s when the magic happens.

What was your first project?

The intersection came when I had an assignment for New York Magazine to photograph the High Line, something that really captures the scale and its context to the city in a way. I spent several days scouting and looking. I became enchanted by this perspective that when you’re on the High Line you can sort of recognize the people on the street corner and then look up and see people in the building windows. It has this very unique scale to the city.

I fell in love with it around noon, when people were having lunch and chatting. Then I came back at 10:30 PM and it was spooky and had a completely different vibe. I asked to do a day to night, south to north on the High Line and make it into one picture. That’s how it really started. After I did that one, there was an amazing reaction to it online. Then I did a second one of Washington Square Park and it was through those two experiences that I began to really realize I stepped into this concept of compressing time in a two-dimensional image.

How does sitting in what you call a “catbird seat” change your perspective?

The work started as a love affair with New York. When I began to work, I became fascinated by what the energy looks like when we all walk around and describe a city. What does it look like when you get above it? As I began to explore this concept, a sweet spot of about 40, 50 feet in the air, life begins to move almost like schools of fish. People don’t look like individuals anymore, it all becomes this flowing river of emergent behavior. How people adapt and move. The more I did in the city, the more I became fascinated by this narrative I was witnessing.

When you’re 40 feet in the air in New York, you’re invisible. It’s a seat where you’re watching people and nobody sees you watching. It’s the ultimate voyeur perspective. When you stay at a place and you photograph for 24, 36 hours, you see things that others don’t see and stories emerge in front of the lens that aren’t really obvious to others. I have this love affair with seeing and looking. I have this visual appetite of constantly finding these magical moments throughout the day and night.

Which view is your favorite?

Coney Island. I don’t think I even ate a sandwich there because I was afraid of missing how amazing the people were. A constant stream of all walks of life. When you describe New York as a melting pot, Coney Island is a place where you really see it all.

What emotion does this type of photography elicit from you?

For me these photographs are capturing a unique moment in history. When I can photograph an actual historical event in context, it elevates it even more for me. Who knows, 100 years from now someone could look at these pictures, like a piece of amber, and see what a day was like. It’s frozen.

A photograph can tell the story of a moment in time while I’m compressing hundreds of moments in that photograph. It touches people in a way that’s exciting to see, the way they engage in the work. People can sort of walk into the photograph and explore it, they spend time looking at it, and I’ve spent time creating it. There’s this connection between what I’ve put in versus the amount of time people want to look.

It’s an informative process.

Is there a certain moment that stands out?

Right now, I’m moving toward capturing wildlife and animal communication. That really began with a photograph I created in the Serengeti, spending 26 hours photographing the watering hole. I was there during the peak migration. There was a drought going on for five weeks and I discovered all these animals by the watering hole. I was able to set up my truck and what I witnessed was nothing short of biblical.

All of these competitive species were all drinking and bathing in the water. There was never a grunt or a scowl. They all dropped their guard. When it came to the water, everybody shares. For me to see this, these animals have another level of communication that we don’t have, sharing the precious resource of water, really was an “ah ha” moment. I’d be applying what I’d be seeing in the world and in wildlife to an upcoming series for National Geographic of bird migration.

Tulla Booth Gallery is located at 66 Main Street in Sag Harbor. Visit www.tullaboothgallery.com or call 917-488-1229.

nicole@indyeastend.com