A Walk Down Memory Lane With Hilary Osborn Malecki

“If I could go back in time,” said Hilary Osborn Malecki, “I’d have some of the strawberry ice cream that was made back then.”

“Wainscott was known for its strawberries. The milk and cream were fresh from the farms and the ice to make the ice cream came off of Wainscott Pond. The children would run it around to the old ladies who couldn’t come to get it themselves,” she said. “My great grandmother Ruth Hedges Osborn wrote in her diaries about making strawberry ice cream and she was famous around Wainscott for her coconut cakes, and I am famous among my friends for her coconut cake too!”

A 10th-generation Osborn, Hilary grew up in Wainscott and has spent 15 years piecing together her family’s genealogy. “I was cleaning out the attic of our family home and ran across diaries and letters that were stored there. I saw that some of the ink was fading, making it hard to read them. I didn’t want to lose the history behind them so I started transcribing them.” Reading these personal diaries and letters gave Malecki a view of the everyday lives and events of her ancestors unlike anything found in a history book.

“In 1637, many of the prominent businessmen in England were not happy with the King. The group of 20 to 30 men and their families boarded The Hector and took off for what is now New Haven, CT,” Malecki said. “Once the king realized that he lost some of his best citizens, he passed a rule that you had to ask permission to leave. The Hector was the last boat to go without asking permission,” she said.

“The first Osborn had a very large family. It’s a shocking story of how they all lived through it. Then in 1648, Lion Gardiner said he was going south to what is now East Hampton and he became the leader of the group. The first Osborn was one of the men in the group and is credited as one of the founders of New Haven, CT, and subsequently East Hampton. The Osborns lived where the Maidstone Arms is now. Some of the Osborns went to live in Wainscott and some stayed in East Hampton, which was originally named Maidstone. For reasons unknown,” she added, “the Wainscott Osborns spell their last name without the ‘e’ while the East Hampton Osbornes kept the original spelling. And,” she added, “The Wainscott settlers became known as ‘Dumplings,’ just like the East Hampton settlers are known as ‘Bonackers.’”

In addition, Malecki’s ancestry research and the diaries and letters that she has transcribed indicated that, “My great-great-grandfather Thomas Osborn was born in 1807. He was a wealthy farmer and supplied horses to the Civil War efforts and would also supply meat to the whaleships when the men went out whaling. He died in 1867 when he was 60 years old. My grandfather, Raymond, was born in 1891 and had a twin brother, Leroy. They lived in nearly identical houses across the street from each other their whole lives,” Malecki said.

Stories Of Sorrow And Community

Having attained a special view into the lives of her ancestors, Malecki said sadly, “So many people died during those times though. There would be an entry in the diary that would say a neighbor’s baby died or someone lost a baby. There was also a sad story about a two-year-old that drowned in a horse trough. There was a ton of sadness,” Malecki said.

“There was no 911 service you could call in an emergency, and even if you broke a bone, you had to wait for a bonesetter to come. There was a doctor named Dr. Sweet that would usually come once a week. Everyone was intimately involved in each other’s lives because they had to be. They helped each other because it was necessary for survival,” she added.

According to Malecki, “In the winter time when Wainscott Pond would freeze, the men would all go out together and they would cut slabs of ice and use the horses to drag it out and put it into an ice house. Each man had a turn to get his ice. When they were done for the day, the wife cooked and fed all the men. They were dedicated to each other and to their community, which revolved around their church. They attended church on Sundays. This was the only day that they had to rest from their hard, laborious week and relax with their families and friends.”

Charles Osborn, Malecki’s father, was born in 1928 in the family’s Wainscott farmhouse. “His father, my grandfather, ran an active potato farm back then and was a big employer in Wainscott. My father was a potato farmer too and he married my mother Dotty. She was from Montauk and was a member of the Choral Society,” she said.

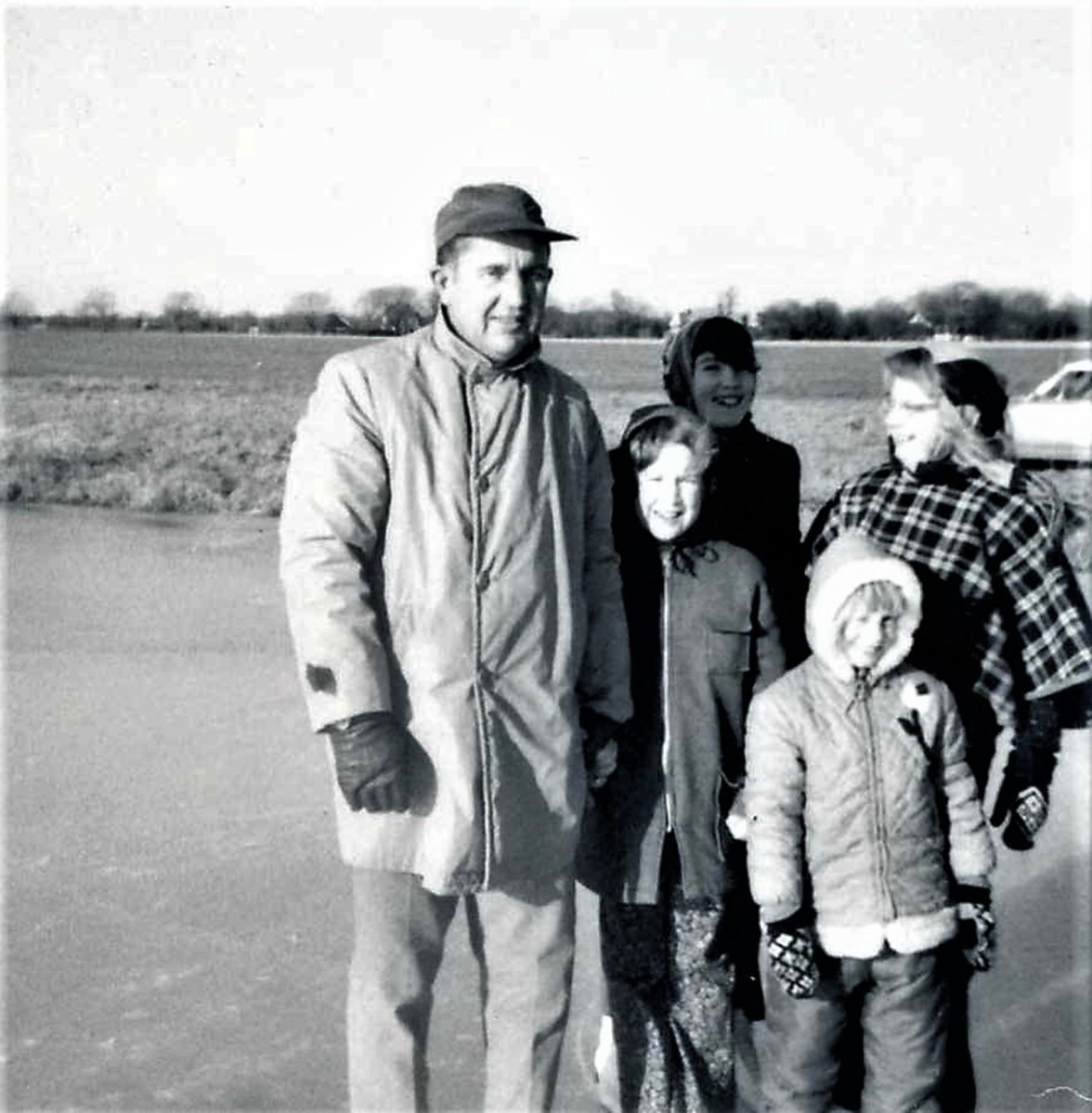

Malecki has two sisters. She remembers that her father would occasionally take her, and her sisters Cynthia and Amy and their friends ice skating on Wainscott Pond when they were young. But Malecki had heard stories in her youth that many of her ancestors had drowned in the pond and admitted, “I was always scared to death to skate on the pond, but knew my father was very cautious and would know when it was safe.”

A member of the board of trustees for the East Hampton Historical Society and a Wainscott Osborn, Malecki’s knowledge and historical documentation of her own heritage has enabled her to give historical presentations about the early settlers as well as to present a two-part series last February that had addressed the flu pandemic of 1918. “The flu,” Malecki stated, “was deadlier than the Plague. A lot of people don’t realize it, but 675,000 Americans died from it. We always like to think of the old days as the ‘good days.’ But it really wasn’t like that for the settlers. The diaries and letters really tell the story. Their lives were very difficult. It’s just so hard to conceptualize it now. So hard to understand how strong they had to be to survive. Their spirit and will, their community, their core family values and faith, no doubt carried them through.”

valerie@indyeastend.com