What’s Next For Deepwater?

When Ørsted, the Danish power company, gobbled up Deepwater Wind last week for $512 million, it did so to keep pace with international rivals who control the offshore wind farm industry; the United States, a newbie in the use of wind-generated power, nevertheless finds its ocean floor leases almost completely owned by foreigners.

Deepwater Wind, one expert theorized, probably was given just enough rope by D.E. Shaw, the hedge fund that owns it, to get the South Fork Wind project going before it was put up for sale.

John Droz, an anti-wind activist and founder of the Alliance for Wise Energy Decisions, theorized that Shaw’s investors may have gotten cold feet as delays mounted for the South Fork Wind Farm. Ørsted, on the other hand, is a huge power entity with unlimited funds at its disposal. Ørsted is the largest offshore wind farm company in the world, with a market share of 16 percent. The company owns more than 1000 operating wind turbines in waters all over the world and thousands more to come.

That 90-megawatt Deepwater project earmarked for East Hampton Town has become the subject of intense debate and is facing a lengthy state review before construction can begin.

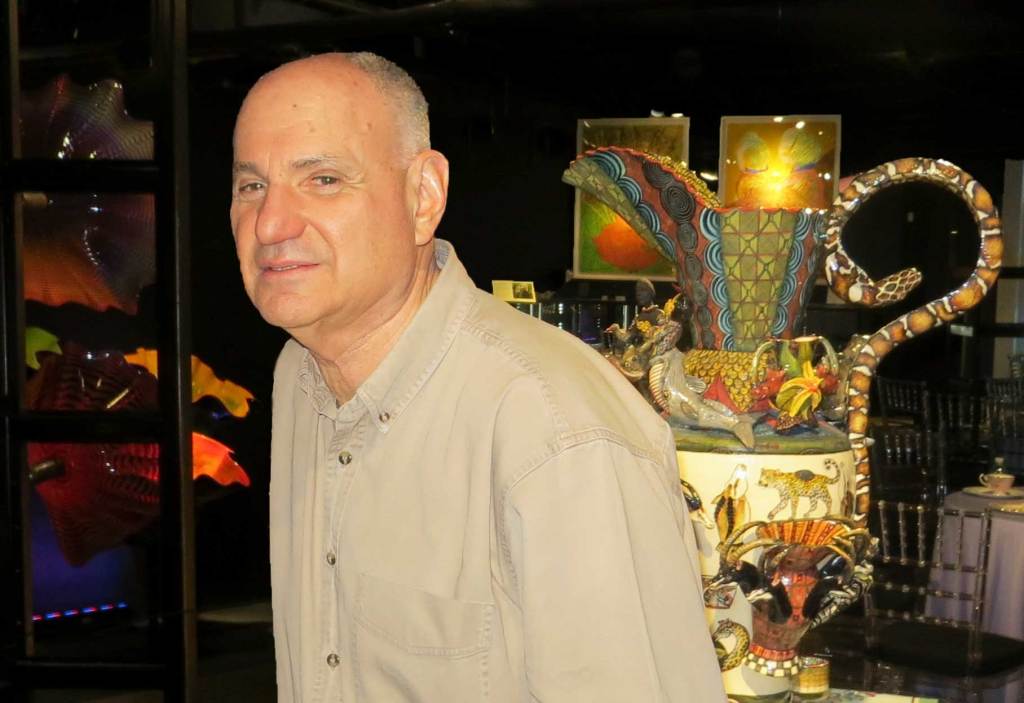

But Clint Plummer, a Deepwater vice president who has shepherded the project through the review process in East Hampton, said that Deepwater’s South Fork Wind Farm — 15 turbines off the coast of Montauk — is ready for state review, “and stronger” because of the 18-month process of getting input from the community, critics, and supporters alike. “We are very proud of it,” he said.

Critics like Droz and Tom Bjurloff, an energy consultant, say LIPA and Deepwater have never been truthful with the public and East Hampton Town officials. Bjurloff said long-term industry plans are crystallizing and will become public probably at some point next year, and when the ink dries the worst fears of critics would be revealed: East Hampton Town doesn’t need the power from Deepwater, and never did. But the players in the deal need the local foothold the small-town government is set to grant them — not to bring power into East Hampton, but, as critics claim, to funnel a massive amount of wind-generated power west, probably all the way to New York City.

Wainscott is slated to become the loading dock, though LIPA officials, like its CEO Tom Falcone, deny that scenario.

“The grid on the East End is very weak,” Plummer said. It would be very difficult to bring more power in. “Part of our commitment is there will be one cable and one cable only,” he added.

Officials from LIPA and Deepwater have been vague about the master plan because of contractual restraints and because unveiling the details would weaken their bargaining chips in upcoming negotiations, and thus increase costs.

Plummer said he, too, was restrained from talking about certain spaces of the project and of future plans because of the deal with Ørsted. “I’m limited in what I can say, but we are standing by our commitment to the community,” he said.

New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo has called for an additional 2400 megawatts of wind driven power by 2030; the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management is being pressured to award leases for 1200 megawatts in December. Of that, 800 will come from the area in the Atlantic called the New York Bite and 400 from points north and east of East Hampton, off the Massachusetts coast.

Ørsted and its rivals will be among the bidders. “I can’t talk about hypotheticals,” Plummer said.

As for the charge Deepwater is gearing up to lay conduits for at least four times as much power needed to solve East Hampton’s “peak” problem, Plummer was perplexed. “I have no idea where they come from,” he said. “I find the assertions ridiculous.”

rmurphy@indyeastend.com