Visiting LI Indians: Thomas Jefferson Transcribed Unkechaug Language

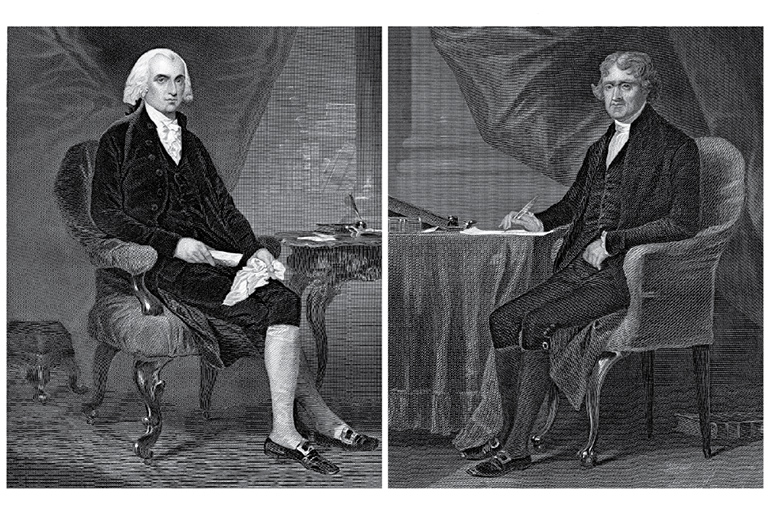

In early June of 1791, James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, both of whom would later become President of the United States, embarked on horseback from New York City to visit some of the countryside surrounding that place. They went first up the Hudson River to Lake George to visit Fort Ticonderoga, which the Americans had seized from the British during the Revolution a decade before.

From there they rode east into Vermont, and thence down the Connecticut River to New Haven, where it was their intention to ride along the Connecticut shoreline and back to New York City and then to Philadelphia, America’s capitol city, while the new capitol was being built in Washington.

They didn’t leave New Haven for New York, though. Instead, at Jefferson’s urging, they crossed Long Island Sound by boat, then spent the night at an inn in Southold in the company of the prominent East End resident Ezra L’Hommedieu, then rode on to Center Moriches, where they spent another night.

The purpose of this detour was to ride to Mastic, a village on the south shore just to the west of Moriches, to meet some members of the Unkechaug Indian tribe, who Jefferson had been told spoke an unusual dialect of the Algonquin language. Jefferson, as you probably know, had an interest in many things. He was a planter, a builder, an architect, an astronomer and a statesman. He also had an interest in Indian languages, and prior to this trip had, using translators, written down many of their words and phrases. At this time, the Indian population in the Northeast was in decline. This would be a unique opportunity for him.

Jefferson, at this time, was in his late 40s. He had written the Declaration of Independence as a young man in his early 30s. Now he was the Secretary of State in the administration of our first President, George Washington.

Madison at this time had just turned 40, was a member of the House of Representatives from Virginia and had written the U.S. Constitution. He and Jefferson owned plantations in Virginia and were close friends. Now it was summer vacation and they wanted to explore. Neither had been to New England, and neither had been to Long Island.

In a way, though, they were taking a cue to take this trip from George Washington, who the year before, in 1790, had gone out to the east end of Long Island. Washington was at that time in the second year of his presidency. After a vigorous life on horseback as a Virginia planter, an Indian fighter, a surveyor and a general surviving a terrible winter at Valley Forge, he was having trouble getting used to sitting behind a desk at his presidential office in Philadelphia, doing paperwork and refereeing arguments between Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton, a New Yorker who had argued that America’s future should be as an industrialized nation and not an agrarian nation, as espoused by Jefferson and Madison. Washington mostly agreed with Hamilton. But now he was ill.

In prior years when he’d get sick, he’d go on long rides to restore himself. So that is what he wanted to do now. In particular, he wanted to meet with the members of the Culper Spy Ring in Setauket, Long Island, who had helped him win the war. He’d never met them personally. He was now 68 years old, however.

And so, instead of coming out to the island on horseback, he came out in a horse-drawn stagecoach, with his staff handling his favorite horses coming along behind. Washington stayed at Sagtikos Manor in Bay Shore, an inn in Patchogue, and then rode up to the north shore at Setauket, where he met some of the members of the spy ring.

RELATED: Culper Spy Ring Sites on Long Island

He really wanted to continue further out east, but because of his illness he did not do so and instead returned to New York City, where he had been staying at the home of Governor William Clinton. His whole trip was completed in just four days, and it did restore him. He lived into his 70s.

Now in that following year, Jefferson and Madison had breakfast at an inn in Center Moriches and then met up with another prominent East Ender, William Floyd, another signer of the Declaration of Independence, who escorted them down from that place to his plantation and mansion in Mastic, not far from where the Unkechaug Indians lived in modest shacks along a salt creek, earning a living hunting and fishing. They spent the night at the mansion, and then Jefferson, alone on horseback, rode off to meet with the Unkechaugs, who he found, largely spoke English.

Eventually, however, the Indians did introduce him to three elderly Indian ladies who spoke the old language, and so for several hours, Jefferson sat with them and, in a notebook, transcribed the words they said and, using an Indian interpreter, what those words meant. He was excited with the success of his mission. Whatever happened, he had saved this language. It could be reconstructed.

Years later, when Jefferson’s presidency ended in 1809, he placed his notebooks along with many other papers in a trunk to be sent to his home at Mount Vernon, Virginia.

It never arrived. Jefferson, very upset, ordered an investigation. They soon found what had happened, and they arrested a stevedore working on the docks along the James River. This man, never named in any accounts that we know, had stolen this trunk, thinking it contained valuables. Opening it, he discovered the papers, but unhappy with his find, he dumped all the papers into the James River. Soon, the man was arrested.

Jefferson wrote a letter to a friend about this.

“An irreparable misfortune has deprived me of the Indian vocabularies which I had collected. They were packed…with about thirty other packages of my effects, from Washington and, while ascending the James River, this package, on account of its weight and presumed precious contents was singled out and stolen.

“The thief, being disappointed on opening it, threw into the river all its contents, of which he thought he could make no use. Among these were the whole of the vocabularies. Some leaves floated ashore and were found in the mud, but these were the very few, and so defaced by the mud and water that no general use can be made of them.”

A few months later, he wrote a further letter to another friend. The culprit had been put on trial, he wrote. And he will no doubt be hanged.

That no general use could be made of the pages was not quite accurate. In the 1920s, East Hampton historian Morton Pennypacker made copies of the Unkechaug vocabularies that survived, and these copies are today stored in the Long Island Collection of the East Hampton Library. Today, incidentally, the Unkechaug Nation occupies a 77-acre reservation in Mastic, where about 500 natives live.

In 1792, two years after Washington’s trip out east and one year after the trip made by Jefferson and Madison, Washington appointed Ezra L’Hommedieu of Southold to oversee the construction of a lighthouse to guide mariners safely around Montauk Point. Thus, the graceful Montauk Lighthouse was built at Washington’s order and became operational in 1797, the first Lighthouse constructed in the State of New York and today the most well known historic monument on all of Long Island.