Santa's First Letter: Read This Hamptons Christmas Fable to Your Children

Early that morning, six days before Christmas, grandfather wandered into the kitchen to make himself a cup of tea. In the kitchen was his seven-year-old grandson, sitting at the table, writing a letter.

“Let me guess,” grandfather said. “You’re writing a letter to Santa Claus.”

“Yup. I want the new Spider-Man PlayStation game.”

“Have you been good?”

“Yup.”

“You know, until I was 10 years old, I couldn’t write a letter to Santa Claus.”

“You didn’t know how to write?”

“I could write. But there was no mail to the North Pole. Back then, before cars and busses and trains, it was too far away and the snow was too deep for the horses of the Pony Express to get through.”

“I’ve heard of the Pony Express. ”

“They never did get through. But then, when I was 10 years old, mail delivery did start to the North Pole. By balloon.”

“How did that happen? ”

“That, young man, is a very long story. But if you’d like to hear it, I’ll just finish brewing this pot of tea and I’ll sit down and tell it to you.”

We lived on a farm on Steven Hand’s Path in East Hampton back then. Everything was farms, and we had neighbors who raised cows and other neighbors who raised sheep, and my dad, he raised goats and chickens, so we always had eggs—scrambled eggs every morning—and we had goat milk. Did you ever taste goat’s milk? No? Well, you’re not missing anything. And of course, we each had horses. My dad had a horse, and my mom, too, and my sister Edith—you know your Great Aunt Edith, she had a horse, and so did I, and his name was Pal.

That year, I wanted a bicycle real bad. They had just been invented, bicycles, and they had a picture of one in the big thick Sears Catalog we got that September, and I had never seen anything like it. So I told my parents about it. They didn’t seem very interested.

“Looks dangerous,” my mother said.

“No, it’s not,” I said. “Look here, it says so right in the catalogue. A PERFECT GIFT FOR BOYS AND GIRLS OF ALL AGES.”

My father looked up from the newspaper he was reading.

“You know, mother, this is the first time this boy has actually asked for something for Christmas. His sister makes whole lists. He just takes whatever he gets. We shouldn’t discourage the boy.”

“Well, son,” my mother said, “you put it down on a piece of paper and I’ll see what I can do.” She turned and started to walk away. “But I wouldn’t count on it.”

The way she said I shouldn’t count on it, I knew that was the end of it. So I said, “Why don’t we put it in an envelope and give it to the Pony Express man to deliver to the North Pole.”

My father ruffled the newspaper. “There is no mail delivery to the North Pole,” he said. He cleared his throat. “Too much snow. Horses can’t get through.”

You know how when you’re a kid you learn new things every day? Well, that was the first I’d ever heard that Santa Claus didn’t get mail. It certainly was a surprise to me.

That night, I lay in bed in the dark, wondering, if Santa Claus never got mail, then how did the lists of things that little boys and girls wanted, like the lists my sister made, ever get to him? I concluded that they did not. And I decided there ought to be a first time. I really wanted that bicycle. And so, I would write a letter and somehow, some way, I would deliver it to him. It couldn’t be THAT far.

I got out of bed, lit a candle on the table in my room and wrote Santa Claus about the bicycle. It was late at night and everyone was asleep. There in the quiet and the dark I thought, Why not deliver that letter right now?

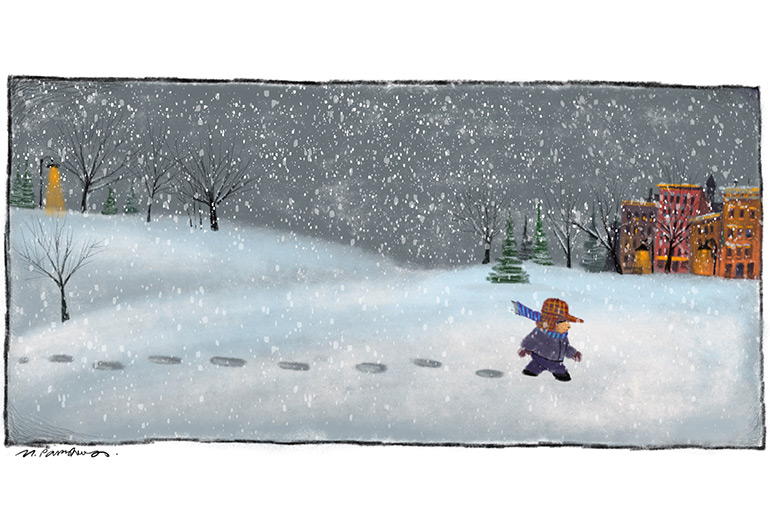

I opened the window and the cold blew in. But it didn’t seem too bad. All I had to do was dress warm. I went to my closet and I put on my warmest clothes, layer upon layer, just like I was going ice skating, then I put on my heavy boots and I climbed out the bedroom window and down the drain pipe.

There was no moon at all that night, but there were a million stars to light the snowy landscape. I trudged quietly through the snow to the barn.

Well, Pal wasn’t asleep, either. I think he must have heard me coming, because when I opened the barn door, there he was, standing right there. He pawed the ground and snorted white steam as I came in, and he let out a whinny.

“Easy, boy,” I whispered.

After he calmed down a bit, I put the saddle on him. Then I climbed aboard. And so we headed out, first at a slow walk, but then as I got farther and farther from the barn, up to a trot, then a cantor and finally, for a while, a full gallop, just because Pal seemed to feel like it. Then we slowed down again. We had a long way to go.

We cantered down Stephen Hand’s Path and then along the Montauk Highway. They did call it a highway then, though it was just a big dirt track, and soon we had gone through Southampton and Westhampton Beach and Patchogue and all the way to the west end of the island, and then we stopped.

In front of me was the great expanse of the East River. No bridges crossed this river back then, but there were ferryboats all the time. What I had forgotten was that in the middle of the night, they weren’t running. I felt very discouraged for a while, and I thought, well, I guess this is the end of it.

Pal and I paced back and forth there along the shore. And then I got an idea. The whole river was frozen over. You could see this one place where an icebreaker had come in and had opened a passage for the ferry between the dock on Long Island and the dock on Manhattan. But for the rest, there was just the ice.

“You stay here, boy,” I said to Pal. “This ice is too thin for you.”

The thing was, I was worried it was also too thin for me. What if I fell in? I tethered Pal to a tree. Then I took down the rope coiled on the saddle, and Pal and I had a long talk.

“I’m going to tie one end of this rope around my waist,” I told him. “And I’m going to tie the other end to your saddle. Keep an eye out. Anything happens to me, I fall through the ice or anything, give this rope a pull.”

Pal whinnied.

And so it was that I started across the ice. It was a long walk, and the ice creaked and groaned, and then it made a loud cracking noise. I stopped. On the shore, Pal whinnied and grabbed the rope in his teeth. But the cracking stopped.

“It’s okay,” I shouted. Pal dropped the rope, and I continued on.

In about 20 minutes, I made it all the way across the ice. When I finally stepped on a snow bank on the Manhattan shore, I heaved a big sigh of relief. Then I untied the rope from my waist and I dropped it to the ground. I’d need it for my return.

There were no skyscrapers in Manhattan back then. There were a lot of small wooden buildings, some three and four stories high, and some of them had white smoke curling from their chimneys from the fires keeping the houses warm inside.

I walked through the dirt roads of town. I’d seen pictures of this place, but I’d never actually been in it. I kept looking around everywhere. On one street corner, there was an Indian lying on a blanket, fast asleep. On another street corner there was a policeman in a blue uniform with silver buttons. He rocked back and forth on his heels. I waved to him. He waved back.

The streets were all lit, even in the night, by big lanterns hanging high from wooden poles up and down every street. I’d seen gas lanterns before, but I’d never seen lanterns lit all night. It made me wonder where they got all that whale oil from. And if they really needed to keep those lanterns lit all night.

And then, up in a field that had a wooden sign out front reading Central Park, I saw something I had never seen before. I rubbed my eyes. It was a big gas balloon. It must have been 60 feet tall and it was all painted up with stars and stripes and it kind of moved back and forth slowly in the wind. Ropes held down with sandbags kept the balloon tethered there.

Under the balloon was a big wicker basket, and there was this man, a little man with a black beard, standing in the basket, tinkering with some knobs and gauges.

I walked over. This absolutely frightened the daylights out of him.

“Oh,” he shouted in this high, creaky voice, almost falling backwards out of the basket and onto the ground.

“You scared me half to death. Do you always sneak up on people?”

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I’ve never seen a big balloon like this.”

“What’s a young boy like you doing out in the park at this hour, anyway?” the man said. “Shouldn’t you be at home, asleep?”

“I’m on my way to the North Pole to deliver letters to Santa Claus,” I said.

That seemed to bring him up short.

“That’s a long, long way on foot,” he said.

“I know.”

“You know, they don’t have mail delivery to the North Pole.”

“That’s why I’m going there.”

“Well, I could probably get you there pretty fast in this balloon.”

“You could?”

“It works fine at night. Goes thousands of miles. But during the day it won’t go anywhere. Just stays on the ground. I invite people on board to show them a ride in my new invention and nothing happens. They just laugh at me.”

“What’s wrong?”

“I can’t figure it out. It should work. But the frammis gets warm when the sun comes up and it just won’t go. I’m ready to chuck the whole thing. I’m also working on an electromagnetic machine that stops time.” He scratched his beard. “But I can’t get that to work at all. Even at night.”

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“Dr. Bixbee,” he said.

“Mine is Billy.”

“Well, climb in, Billy. I’ll take you to the North Pole.”

What a feeling it was to leave the ground and head high up into the night sky over the city of New York. Dr. Bixbee worked the controls. I held on for dear life. We floated over to New Jersey, then across Pennsylvania to Minnesota, then up to Alaska with all the igloos down below, and then right to the North Pole itself.

There was absolutely no way you could miss it. You wouldn’t have believed it. The North Pole is a big red-and-white striped pole a hundred feet tall. It is a giant candy cane.

We came thumping down right next to this pole, in between the pole and a whole group of buildings. Immediately we could see all sorts of little people running around. What a busy place. It was the middle of the night, and people, little people, were carrying boxes and gift-wrap this way and that. It was Santa’s workshop.

We climbed out of the basket and, with the ropes and sandbags, secured the balloon. Now the elves began running over to us, talking excitedly and jumping up and down until there were maybe a hundred of them, forming a big circle around us. And then, suddenly, there he was, Santa Claus, pushing through the crowd.

“Well, well, well,” he laughed. “What have we here?”

Dr. Bixbee held out his hand. “I’m Dr. Percival Jonathan Bixbee,” he said, “and this is Billy. We come from New York.”

“That’s a very long way,” Santa said.

“Indeed it is. And I have brought you something very special. Billy here has brought you a piece of mail. Addressed to you.”

“Mail?” Santa asked. “What’s mail?”

“That’s right, you don’t know what mail is,” Dr. Bixbee said. “It‘s writing on a piece of paper. People do it all the time. They write messages down and they give them to each other.”

“We don’t get this mail thing here at the North Pole,” Santa Claus said.

“Well, here’s the first. Billy? Give Santa Claus your letter. It’s a request, Mr. Claus, for something that he wants for Christmas very, very much.”

And so I reached into my pocket…and it wasn’t there. I reached into another pocket and it wasn’t there, either. I tried another pocket and then another. I took off my mittens and I tried every pocket. And that’s when I realized I had left my letter on the table by my bed in East Hampton.

“I came all this way,” I said, “and I left it home.”

And then I started to cry.

“Oh now, now,” Santa Claus said. “You mustn’t cry. This is the North Pole.” He came over and put his big arm around me. “If it’s something you want for Christmas, you’re here and you could just tell me about it.”

“A bicycle,” I sniffed.

“Oh yes, those new things. What color?”

“Red. ”

“What size?”

“I don’t know.”

“Well now, we’ll measure you up.”

Santa Claus snapped his fingers and an elf stepped forward. “Measure this boy for a bicycle,” Santa said. The elf took out a long silver rope, held one end at the top of my forehead, put the other end on the ground, and then turned to the crowd.

“Three hundred sixty one and a quarter,” he said.

In the crowd, an elf took out a pad and pencil and wrote it down.

“That takes care of THAT, ” Santa Claus said.

I smiled. I was so happy.

“Do you need to know where I live?” I asked.

“Oh, we know where you live. That we have in a book. We also have a book that tells if you’ve been bad or good.”

“I’ve been good,” I said.

“I have no doubt.”

“You know, Santa Claus,” Dr. Bixbee said, “I could deliver mail to you every night all year long from little boys and girls describing what they want.”

“That would be wonderful!” Santa said. “It would take out all the guesswork. You’ve got yourself a job, Dr. Bixbee.”

And then Santa put his other arm around Dr. Bixbee.

“This calls for a celebration. How would you two like a tour of my workshop?” he asked. “I’d like everybody to meet you.”

I could hardly believe it. I looked at Dr. Bixbee.

“We have time for a quick one,” Dr. Bixbee said. “I just have to get back by dawn.”

And so off we went. We went into the workshop, where hundreds of elves were making toys and putting them in boxes. We went into the warehouse where there were more presents than I’d seen in my whole life. We went to the stable and Santa introduced us to the reindeer, and we even went into the garage where they were polishing up the sleigh. Then we met Mrs. Claus. She was a big, jolly woman and she gave us hot chocolate and biscuits, which we ate and drank right there on the spot.

But then Mr. Bixbee looked at his watch and said it was time to go. So Santa and Mrs. Claus, the elves and all the reindeer walked us back to the balloon, and we climbed in and flew off, not back to Central Park as I had thought we would, but to where Pal was tethered on the island side, alongside the ice. Dr. Bixbee set right down next to him in a field of snow. I climbed out.

“Goodbye, Dr. Bixbee. Thank you so much.”

Off to the east, the first light of dawn was beginning to shimmer over the woods of the Flushing Plain.

“Goodbye, Billy,” Dr. Bixbee said, looking at his watch again. “Time to go. The frammis is getting skittish again. But you know, I want to thank you, too. You’ve done a wonderful thing. I was just about to give up with this balloon invention. Now I have a whole business. Dr. Bixbee’s Balloon Santa Claus Mail Express. I’ll put an advertisement in the newspapers as soon as the offices open.

Be good, Billy!”

And then he was off.

I went over and untied Pal and began to reel in the rope I had stretched across the river. It seemed like I’d have just enough time to gallop home, put Pal in the barn, climb up the drain pipe and get into bed before breakfast.

“And that, young man, is how I got my letter up to Santa Claus. And how balloon mail delivery started to the North Pole for the very first time.”

Grandfather took a last sip of tea, stood up and put the cup in the sink.

“Is this story really true, Grandpa?”

“Of course it’s true.”

“You don’t have a red bicycle.”

“You finish that letter, young man. And when you get it done, you put a stamp on it and give it to me, and I’ll give it to Dr. Bixbee. You do know that your letter will get to the elves at the North Pole now, don’t you?”

“Of course I do.”

“Well, there you are,” Grandfather said. And he smiled breezily, turned, and walked out of the kitchen and into the living room.