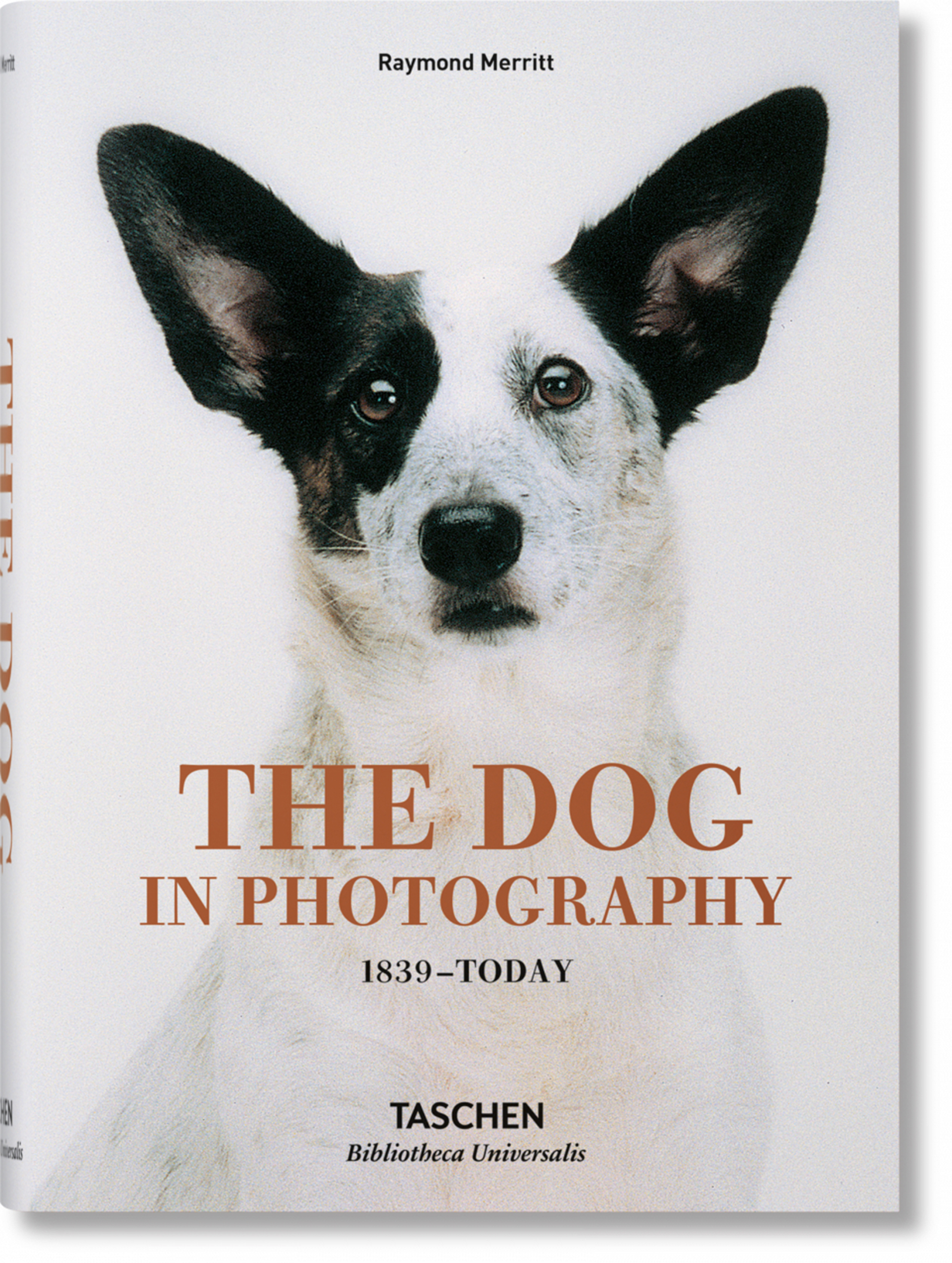

The Dog In Photography: 1839-Today

North Haven resident Ray Merritt may be a senior partner with an old-line international law firm, but his creds also include being deeply involved for decades with art and photography. A trustee of the International Center of Photography and a member of the acquisitions committee of the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Norton Museum in West Palm Beach, he collects art, curates exhibitions, and has edited several books on photography. He has also always had an abiding love of dogs (he has two, a mixed breed and an African hunting hound).

These two passions are joined now in a tri-lingual (English, German, and French) volume dedicated to photographic images of what Ogden Nash once famously declared “man’s best friend.”

A handsome, hefty five-by-seven-inch book, The Dog in Photography not only delights with all manner of dogs, poses, and contexts, but informs: This is cultural history in the tradition of following a particular subject through time. Here, two strands come together: the creature “inextricably linked to man . . . by a bond that began at the birth of human civilization,” and the predominant mode of communication in the world since the start of the 20th Century.”

Merritt notes, by the way, that the reason photography is so popular in small-book format “is that it is closest in size to the original,” as opposed to fine art photography, which is usually printed as nine-by-12 inches, while painting and works on paper and sculpture are typically even larger.

Dogs want eye contact with us, Merritt points out, more than they do with their own species, and “they seek us out when they’re scared or worried, while cats and horses run away.” It would not be until the late 19th-early 20th Century, though, that portraits of dogs would emerge as subjects for fine artists as well as for the early photographers, testimony to man’s love for the dog as noble beast and heroic companion, not to mention faithful adventurer. Merritt reminds us that Ernest Shackleton took 27 men and 60 dogs with him to the Antarctic in 1914.

The juxtaposition of the two strands — dogs and photography — is hardly accidental. As Merritt notes, “The advent of the camera happened to coincide with the emancipation of the ‘underdog’ from feudal servitude.” But what to make of what would become “photographic obsession” with the dog, nay “addiction,” much of it due to the protective aegis of dog-loving Queen Victoria? From the earliest days of daguerreotype, dogs have ruled. Many of them are seen here, embraced by young children and nude women. Dogs stay in our lives forever, Merritt writes, “the children that

never grew up.”

Arranged chronologically in six sections, the book is as much about broad Western history as it is about the evolving relationship between canis familiaris and camera obscura. Sections open with a brief essay about what was happening in the world, particularly America. What the images then show is the growing democratization of dog ownership — even (especially?) the poor have dogs. The dog becomes a sign of prosperity, status, taste, part of the everyday upward-looking family now fitted out with a Brownie Box camera. Merritt celebrates the way the dog has becomes a cultural icon and an affectionate intimate. Images include kitsch as well as art by well-known photographers, a picture of a hot dog a few pages away from scenes of dogs sacrificed to war.

The tri-lingual essays pack in a lot of information, especially on technical achievements. (Oh, those inventive French photographers!) The book is also studded throughout with quotable lively sayings, some gnomic, some fanciful, that show the impressive breadth of Merritt’s literary and historical research into the last 170 years.

Celebs are here, of course, stars of TV shows and movies, along with political figures and their dogs. (Modestly, Merritt includes only at the end a small black and white picture of himself with a dog from 1940.) The first color image in the book happens halfway through, with a two-page spread of the actress Joan Collins and her dog, followed by two up-close shots of collies. The bulk of the book, however, is black and white, the better to appreciate composition

and tone.

In our impersonal, cynical age, dogs remind us of our affinity with other creatures of the earth, Merritt suggests. “It was once said that some of our greatest treasures hang on the walls of museums, while others are taken for walks.” Today, the closeness has deepened with the growing reliance on

service dogs and dogs for therapy.

Great photographers sense great moments. And here they are.