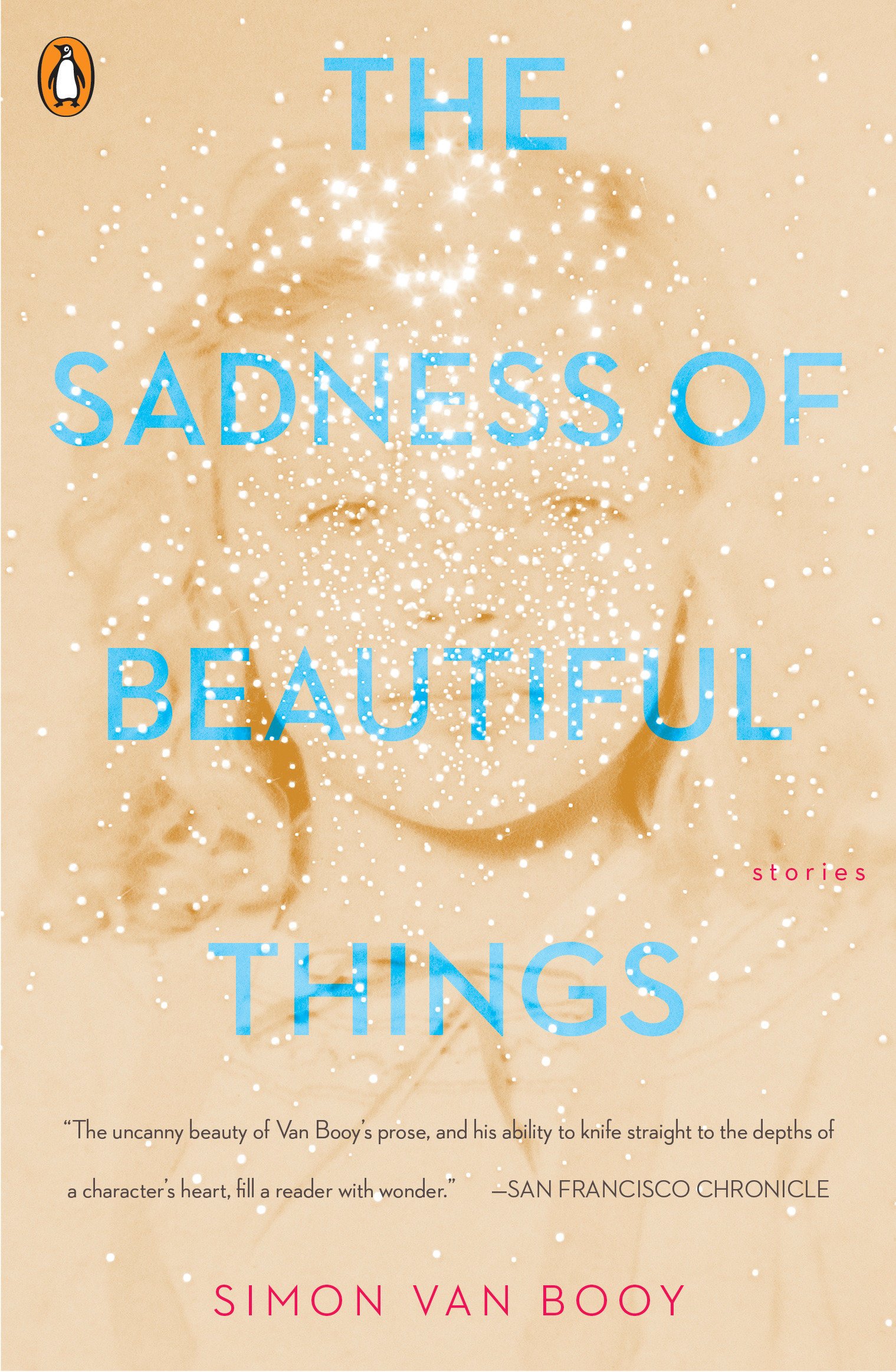

The Sadness Of Beautiful Things

Simon Van Booy seems a well-kept secret on the East End, even though this English-born New York City resident attended the Southampton College Writing Program, lived in East Quogue for years, wrote articles for the local press and taught at, among other institutions, the C.W. Post campus of Long Island University. Then again, he’s been all over the world (his stories reflect his travels to places urban and remote) and has accumulated so many awards and been translated into more than18 languages (including two different varieties of Chinese), it’s hard to believe he’s only 43. A short acknowledgments page notes the original publication of a few of the stories in the Irish Times, the Chinese edition of ELLE, as a BBC commission, and in the Chinese edition of Harper’s Bazaar.

Genre alone cannot define Van Booy, though fans especially admire his eccentric, beautifully executed short stories. He’s also written prize-winning novels, children’s lit, books on philosophy, critical essays, a stage comedy, and short films. As if this sweep were not jaw-dropping enough, Van Booy is a man on a mission, an advocate of “education as a means of social reform.” He’s involved in the Rutgers University Early College Humanities Program for young adults living in under-served communities. And wait . . . there’s more. He designs custom vintage Antarctic explorers’ skis and cold-weather hats, in order to support research in Antarctic regions and raise awareness for the Scott Polar Research Institute at University of Cambridge.

In The Sadness of Beautiful Things, his latest story collection, he once again shows his extraordinary range in region and subject matter, and his skill in evoking sympathy for everyday people as they try to reconcile themselves to loss. Somehow, it all works. The characters act in small or strange ways that bring some kind of peace to troubled or aimless souls. Still, you are left wondering about their lives. The stories end but do not conclude.

The epigraph to the collection is telling: a four-line poem by William Blake (1757-1827): “He who binds to himself a joy/Does the winged life destroy. He who kisses the joy as it flies/Lives in eternity’s sunrise,” which suggests a theme of accepting the transience or evanescence of beauty. Events in a Van Booy story move in strange, sometimes surreal, ways and take unexpected turns.

A prefatory note to the collection states that most of the tales “are based on true stories told to me over the course of my travels.” Two of the tales are long, with short sections that create a sense of mini-epic. “Not Dying,” for example, is introduced as a story about a man the author met when he was in Kentucky, a neighbor who lived alone and never had visitors. A man who is a Native American (not apparent at first) believes for a while that the world will end soon — he’s heard about it on the radio from a preacher-type. Out of great love for his wife and child, both a miracle in his sad life on the Reservation, he wonders what he can do to protect them, if it’s true. He’s not wholly convinced, but is compelled to believe it out of his own fear and insecurity. What happens is deliberately kept vague, but his thoughts, expressed by way of comparisons to the universe, reflect a deeply moving testament to his love.

All of the stories have a kind of once-upon-a-time quality enhanced by resonant poetic comparisons and memorable phrases. “A dream she had been having came apart like tissue in water.” Or there’s a young hitchhiker’s memory of an older woman who stops to pick him up one dark night: “When he closed the door, they stared at one another through the glass, but only her outline was visible. It was the first of many times he would try to remember her face, the first of many times he would look for someone and not see them — search for someone whose absence defined him.”

It’s significant that the collection is titled “the sadness of beautiful things” and not “the beauty of sad things” because Van Booy’s characters, though they seem many of them uncomplicated, uneducated, misguided, act selflessly, even sacrificially, out of an intuitive sense of compassion. In this sense, the tales could be said to be love stories — small, insignificant instances of ordinary man’s humanity to man. Not a bad theme to advance in our hard, cynical age.