Hampton Cove? Let’s Not Allow Any Place Call Itself a “Hampton”

I think the Hamptons should consider passing a law that would prevent any other community on the East End from using the name “Hampton.” We have enough Hamptons. We have Southampton, Bridgehampton, East Hampton, Westhampton Dunes, Westhampton Beach and Hampton Bays. All are time honored. All are special. And sometimes it is confusing enough having to whittle down which Hampton you are referring to when you talk to somebody. Besides, we have the job of protecting the reputation of “The Hamptons,” which, although in fact it exists only as a group of places, is worth its weight in gold, as I am sure you know.

I don’t know if you are aware of this or not, but a number of communities on the East End have tried changing their names to something with a Hamptons. The community of Mastic Beach tried to become Hampton Harbor some years ago, but they failed. Another attempt was made by North Hampton, which only failed when it was realized that this was just an attempt by a developer to horn in on being a Hampton. And before that, in 1905, the summer people in Shinnecock Hills tried to change that community’s name to Hampton Hills, an effort that failed only because when they looked into it, they found that there needed to be a majority vote from its citizens—and in fact, only one individual resided in Shinnecock year around, the postmaster Andrew Terwilliger, and he was against it.

I was reminded of this the other day when I read in The New York Times that the country Macedonia, which was formed after the breakup of Yugoslavia 30 years ago, was willing to change its name in order to be allowed entry into the European Union.

It’s a remarkable story. Back when Macedonia was just a part of Yugoslavia, the southern border of Yugoslavia touched the northern border of Greece. And just below that border, in Greece, there is a province of that country known as Macedonia. Macedonia was the home base of Alexander the Great during ancient times.

On the north side of that province, this small country formed up—many of its citizens saying they were descended from Macedonian ancestors—and announced itself as the Republic of Macedonia. I happened to be in Greece at the time. This was in 1991. It sent shivers through the population and government of Greece that a new country north of the Greek province of Macedonia would decide to call itself Macedonia. How could they do that? People would be confused about that. And their Province of Macedonia went all the way back to Hellenic times, before the birth of Christ, when Greece was in its heyday. (This is even further back than, say Southampton, which goes back to 1640. Or Bridgehampton, which goes back to 1644.)

At the time, the European Union was in its infancy, with only a dozen members, one of which was Greece. The EU wanted more members, but the Union had passed a law that said no new country would be allowed to join if any one country already in the EU filed an objection.

Back when I was there, this matter was too new to have had anything to do with the EU. Joining or not joining the EU was a long way off. The new country did try to join the United Nations, though, and Greece objected. A compromise work-around occurred. It said Macedonia would be allowed to join the UN only if it called itself the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, so that is what they did. Frankly, I thought at the time this is pretty stupid. We have Georgia the state and then we have Georgia the country on the opposite side of the globe, but, well, this was Greece.

Soon, however, other countries were joining the European Union all over the place, and wouldn’t you know, the Prime Minister of Macedonia (the country), at one point, asked to join, too.

Of course, Greece objected. And this resulted in people in Macedonia and the people in the other Macedonia yelling at each other back and forth. And the officials in the EU yelling at the government of Greece for pulling off this nonsense. The EU wanted Macedonia. And Macedonia wanted the EU. I believe that as things stood, this part of the EU for years and years stood out like a sore thumb when you looked at this particular part of it.

Negotiations ensued. And four weeks ago, an agreement was signed. The Prime Minister of Greece, Alexis Tsipras, was photographed shaking hands with the Prime Minister of Macedonia, Zoran Zaev, after they had both signed. Henceforth the Republic of Macedonia would change its name to the Republic of North Macedonia, and as a result of this the government of Greece would drop its objections to Macedonia, now North Macedonia, joining the European Union. Of course, this agreement would have to be ratified by the legislatures of the two governments. And shortly after the signing, the legislature of Macedonia did so.

But Greece was another story. Alexis Tsipras was the Prime Minister of Greece only because he had put together a coalition of political parties, of which his is the largest. Another party in the coalition was the right-wing Conservative Party, and the head of it, Panos Kammenos, had been a vigorous opponent of having anything to do with Macedonia changing its name to anything that continued to have the name Macedonia in it.

“It’s not a deal, it’s a capitulation,” he said. This is what many opponents to having two Macedonia’s say. They fear that the country of Macedonia will someday try to annex Greece’s province of Macedonia since they have the same name.

Greek Prime Minister Tsipras said now that everything has been signed, everybody who has been opposed to this has to do their duty and go along with it.

Angela Merkel, the German Prime Minister, visiting Athens, praised the agreement. She expressed gratitude for leading the efforts to get it done.

A few days later, though, Kammenos announced he was resigning from the coalition. And, he said, if anybody in the legislature from his party said they would go along with what was signed, they were automatically ejected from his Conservative Party.

Tsipris shot back that, without the Conservatives, he would still be able to find enough votes from the other parties within the government to pass the agreement.

He also then announced that he would ask for a vote of confidence from the legislature. These have been tumultuous political times in Greece. There have been six votes of confidence in the last five years, the last three during the reign of Alexis Tsipris. He’d survived them all. He was hoping to hold such a vote at the end of this week.

Of course, if it fails, he will have to call new elections. The issue of Macedonia vs. Macedonia has the potential to bring down the entire Greek government.

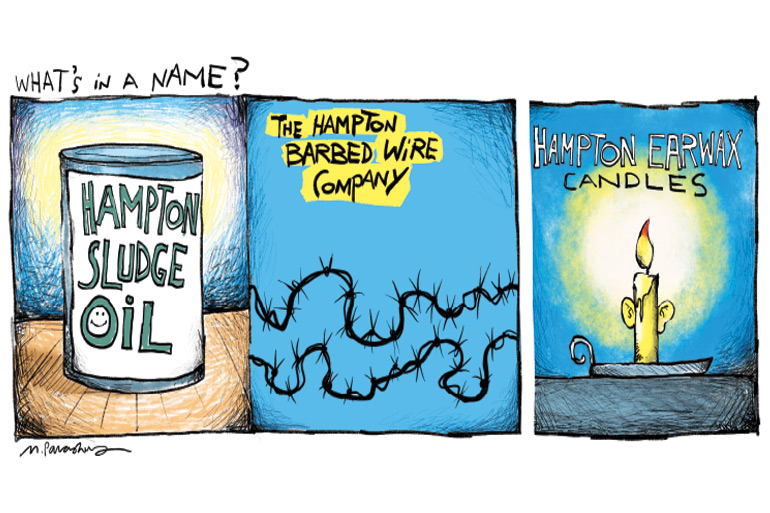

So I submit that we should pass a law prohibiting any community from changing its name to become a Hampton, or even starting up with a new name that included the word Hampton.

You do, of course, know of the thriving village here in the Hamptons that came into existence in 1993 that started from nothing. It was, at the time, just the most easterly part of Dune Road in an unincorporated part of the Town of Southampton. Flooding had resulted in half the homes in this area either unfit for habitation or collapsed into the sea. Now the owners of these no-longer-in-existence homes on underwater properties wanted to band together and form an official village to be called the Village of Westhampton Dunes. They succeeded. It is there today, and the federal government paid to have it rebuilt. I say that because it was part of the Hamptons as Southampton before it came into being and so now has a new name with the word “Hampton” in it, which was also true before, I consider it a sideways jump. And it passes muster.

So if the Village of East Hampton wants to change its name to Hampton East, I won’t object. If they want to change it to Hampton Macedonia, though, I say that’s looking for trouble.