President of Long Island? Settler Asked King Charles II to Grant Him the Title

This is the true story of a man in colonial times who, after meeting with the representatives of all the towns of Long Island, got them to elect him President of Long Island. With that title, he would ship himself off to London to meet the King of England, prepared to ask the monarch to declare Long Island an independent 14th colony with he himself as its head.

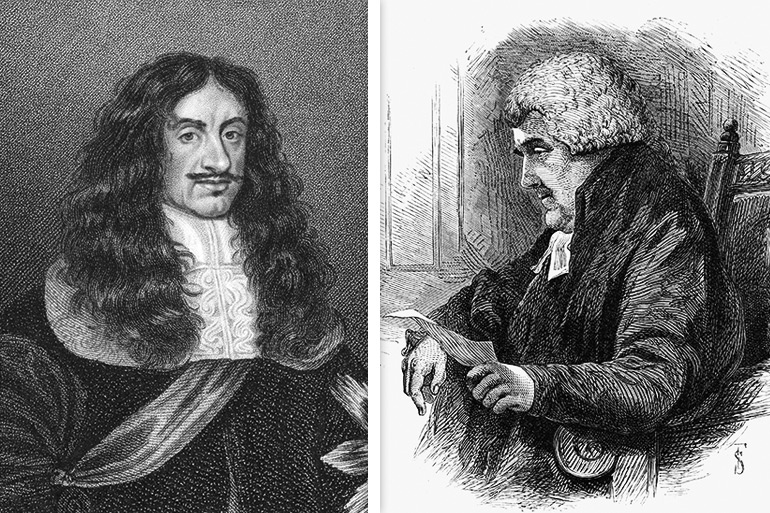

It’s an astonishing story, and the King was at first inclined to grant him his request, though later he was talked out of it by advisors. What is even more astonishing is that at the time, John Scott—or, as he preferred to be called, Captain John Scott—was all of only 26 years old.

I stumbled upon this story some time ago when I was writing about various early wooden bridges built to cross ponds at Mecox and Sagaponack in colonial times, and Scott was indirectly referred to as a man who had swindled local Southampton men out of money in a land scam, after which he left town and never came back. What I had not read at that time was that he had married a local woman, Mary Raynor, built a house on property next to her father’s house in North Sea, and, when he fled, left her destitute with three children.

It’s quite a story.

John Scott was born in England and at the age of 5 was sold by his parents to a Southwick Family that put him to work until, ruined by their anti-Puritan views, they sold him to a purported child trafficker named Emmanuel Downing. Downing had him taken to America—this was during the time of the English civil war—where he continued to work as an indentured servant until he was 21. There is a reference of him as a teenager being accused of accidentally shooting a young girl in Salem, Massachusetts, and then after that being sent to Southold, Long Island, where he worked for a ship’s captain. He was sent to sea for a while, and returned with the title of captain.

This rough upbringing, it seems, emboldened him. After marrying Mary Raynor and moving to Southampton, he claimed to have met with the local Indians, one of whom had deeded him much of Long Island in Brookhaven Township, along with land in Quogue and East Hampton. It was a tremendous amount land, and he had paperwork from the King (through his supposed upper-class family back home supporting it), and so he swapped parcels of it out to local Southampton residents for cash. He dressed his wife in the sort of clothing worn by members of the royal court. He referred to the famous sachem Wyandanch as “an ancient and great friend.” And when asked about his claim as a captain, he said he’d been a whaler, a sea merchant and a fur trader. (In fact, there’s a record of him being arrested with a friend during his time in Connecticut for “plundering” a Dutch ship docked at New Haven. The charge was dropped.)

The locals here elected him a “freeman,” which made him a reputable property owner. He then became an attorney and, subsequently, the Southampton Town Tax Commissioner, and then Southampton Town Supervisor. He was 23. Keep in mind, this was only 15 years after the English founded their communities on Eastern Long Island. There were only a few hundred settlers.

Apparently coming to believe everything he told everybody about himself, he began to complain about the possibility of losing all his land—which at this point amounted to about 30% of Long Island. It could happen if the Dutch businessmen who had founded outposts in New Amsterdam, Flushing, Hempstead and other communities on Long Island, as well as up the Hudson at Peekskill, New Utrecht and other places, expanded east and took all of Long Island.

By the way, at this particular time, Long Island was under the jurisdiction of the colony of Connecticut, whose governor, John Winthrop, who believed his colony’s grant from the King included Long Island. Indeed, the eastern Long Island communities were aware of this. Numerous legal matters here (the accusation of an East Hampton woman as a witch, the case of a Spanish slave ship hijacked by the slaves in transit, which subsequently arrived at Montauk) were referred to Connecticut courts.

In any case, Scott assembled the leaders of all the English towns to a meeting in Setauket, at which time they voted him President of Long Island to go to London to seek a grant from the King for independence.

In London, Scott dressed elegantly, claimed he was a descendant of the Scott family—the Scotts had a castle called Scot’s Hall—and that got him the meeting with King Charles II. Before it, he also met with Dorothea Scott, the heiress to Scot’s Hall. She was charmed by him, and in exchange for 2,000 pounds he agreed to deed her 20,000 acres of Long Island at “Horsesneck.” There is no Horses Neck, or Horsesneck, not then, not now.

At the time, a description of Scott was written down by a London reporter:

“A proper well set man in a great light colored Periwig, rough visage, having large hair on his eyebrows, hollow eyes, a little squint or a cast with his eye, full faced about the cheeks with a black hat and in a straight bodied coat cloth with silver lace behind.”

Here was the meeting with Charles II. He presented himself as the President of Long Island, and asked, simply, to be appointed Governor of this new colony. The King was charmed. He gave tentative approval, but then took the request under advisement and brought it to his Council of Foreign Plantations, who subsequently talked him out of it.

Back to America, Scott presented the King’s correspondence with him (including signatures) to Governor Winthrop and told him of his concerns about the Dutch, and got Winthrop to agree to commission him and a number of Long Islanders to go to western Long Island and require that the Dutch traders that came across the water to sign an oath. The oath, which he announced aloud—in Dutch—said “this country you inhabit is unjustly occupied by your leaders. It belongs to the king of England and not to the Dutch. If you acknowledge his Brittanic majesty’s sovereignty you will be permitted to remain in your homes. Otherwise you will be forced to leave.”

In New Amsterdam, he presented himself to Dutch governor Peter Stuyvesant, requesting a meeting. He signed it President John Scott. And he got that meeting, too, although Stuyvesant would not agree to the demands.

After that, the roof fell in on John Scott. Winthrop, hearing about how Scott had presented himself to the King, ordered Scott’s arrest on charges of forgery, treason, sedition and, among other things, “profanation of God’s Holy Day.” Many Long Islanders went to the Hartford trial of John Scott to defend him. Also defending him was John Davenport, a leader of the adjacent royal colony of New Haven (which later merged into Connecticut). Nevertheless, Scott was convicted by Winthrop’s court and sent off to prison, where he spent three months before (with help) escaping. It was during this interval that the King gave a proclamation to the Duke of York establishing the State of New York, which included all of Long Island. It also included the Dutch surrender of New Amsterdam to the English. But now, the Duke of York was horrified to learn that Long Island had a “president.” He demanded that Scott produce the deeds to all the lands he claimed.

Scott, now just 27 years old, did not produce any deeds. Instead, he fled to the Caribbean, where his exploits involved the takeover (from the Dutch) of islands including Barbados and St. Kitts. He later was instrumental in creating the boundary between Venezuela and British Guiana, but this is to be described at another time. He spent his later years back in London, where he wrote a book about his exploits and, with a cartographer, drew maps.