The Maya: Two Children Died Immigrating from Guatemala and What It's Like There

Two children from Guatemala died on the American side of the border from Mexico last month while in the custody of immigration.

The first was a 7-year-old girl from Guatemala who, accompanied by her father, died at our southern border while awaiting immigration processing. An autopsy is being done. The father, now in El Paso, is staying at a migrant shelter to await developments. Meanwhile, in New York, a New York Times editor dispatched a reporter to the little village of San Antonio Secortez in the mountains of Guatemala to interview this little girl’s mother. Mother and her three other children had stayed home.

The reporter found Ms. Maquin, who spoke neither English nor Spanish but the Mayan language Q’eqchi’ and so agreed to speak through a translator. There had been talk here that maybe the daughter had been sent off while unwell, and she wanted to dispute it. There were no reports that her daughter had been sick or malnourished. Her father would have taken good care of her. He had gone off to find a “better life,” and he had been told he’d have his best chance if accompanied by a child. He’d taken their oldest. Now the child was lost. And no, she did not want her husband to come home. He should stay in America if possible, work and send money home to them.

The second child to die was an 8-year-old boy, also from Guatemala, named Felipe Gomez Alonzo, from a town near Quetzeltenango called Yalambojoch. He was also accompanied by his father. He died a few weeks later on the American side of the border in immigration custody, and again his father remains in America. The cause of death was influenza.

I have an interest in these stories because when I was 29 years old, I lived for four months with my wife amongst the natives in an indigenous village not far from either San Antonio Secortez or Yalambojoch. Dan’s Papers was in its infancy. The winters here were even deader then. So we’d go to a warm place for four months, from November to March.

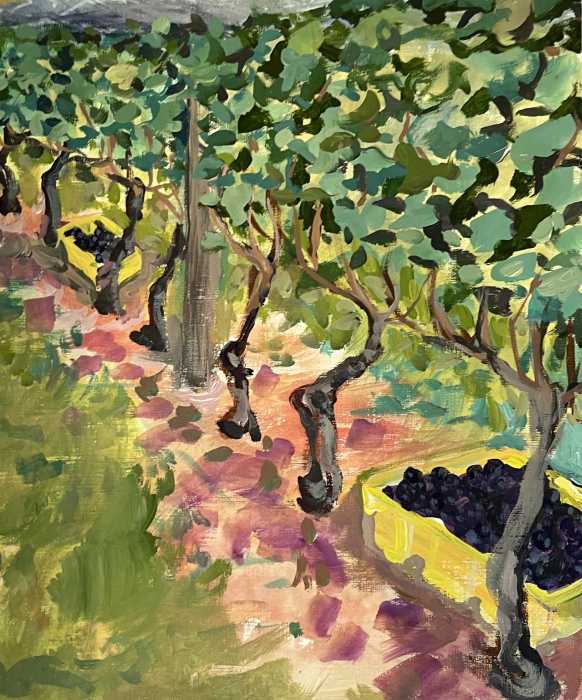

On this trip, our time was mostly spent in a Mayan village called Panajachel, on a mountain lake surrounded by volcanoes. A few dozen other Americans also lived there for the winter. Around the lake, there were almost two dozen tiny native villages linked to one another by donkey trails, and, on foot, we visited some of them. A paved road connected our village to civilization, and trucks and busses used it. But goods and services to the little villages came only by these footpaths. We went to a horse auction in San Francisco Alta once. It was near to San Antonio Secortez. We went to an open market at another village near there. It’s all in a diary I kept.

Nearly half the population of Guatemala is Mayan, many living in these villages. This was true then, and it’s true now according to what the Times reporter wrote. The population of Guatemala is 17 million—40% is 6.8 million. A photo accompanying the story in the Times shows the grieving mother and one of her other daughters standing in the front yard of her father’s home. She and other family members wear the same colorful and identical hand-sewn native clothing unique to each village that we saw.

“…she burrows into the protective embrace of her extended family in a village of thatched-roof homes in the rolling hills of the of the Guatemalan lowlands,” the reporter wrote. “Families eke a living from the land, growing corn and beans, raising goats, chickens and pigs.”

Same deal then as now. “Eke” it out? When I was there, they ate well. All looked healthy and well. Could this be that they just live in another culture that we in the west and that reporter simply do not consider healthy and sanitary?

“Nobody has a television in the village, much less internet access, though the mayor’s press officer has just begin broadcasting a news segment on community radio in Q’eqchi’ in which he warns about the risks of traveling to the United States,” the Times reporter writes.

In the town where we lived, there was one television set, located in a barbershop. People watched through the window outside from the dirt street if the word went out there were something interesting to see. A presidential address, for example. In Spanish. It had to be translated into Q’eqchi,’ this pretty language filled with clicks. The barber would open a window so everyone could hear. Across the street was a one-room movie theater where people came nightly to watch American films.

When we were living there, these communities were getting along the same way as they had for thousands of years. The Times reporter in the current circumstance references a nurse who comes to San Antonio Secortez once every six months, and reports from an examination of this daughter that found her “the right size for her age.”

And a few times a day, a shiny jet flies over the volcanoes.

I recall an American telling me back then that there was great opportunity in the mountain villages of Guatemala. We had been talking about how beautiful these people were, and how you could tell which village they were from by the bright color schemes of their clothes.

“It’s like the NFL,” my friend said. “Every team has their colors.”

He had this idea of asking all the villagers in one of the villages to spend five days a week making hats. He could sell them in America. “They work for a dollar a day,” he said. “Most are unemployed now.”

All the villagers were friendly toward my wife and me. They worked in rice paddies or cane fields. Those who chopped cane carried machetes they tucked into their belt sashes. But nobody ever thought of them as weapons. They carried no weapons. We’d communicate by hand signals and a few words.

Those living there were all smiles. They were curious about us, but also wary. In one of the remote villages we visited, some adults tossed a few rocks in our direction as a warning. Stay away. In another village, a child ran up and begged for money and his mother ran up and grabbed him and chastised him for doing that.

“In a cash economy,” the Times reporter wrote last month, “every Quetzal counts, and Domingo Caal, the 61-year-old family patriarch (the deceased girl’s grandfather) calculates his expenses in terms of how much corn he would have to sell to pay for them.”

An American reporter in Guatemala has her perspective. A brother tells her there’s “no opportunity” in the village. The father keeps his books in his study. She writes of a big plantation owned by foreigners nearby that plants corn used to mix with gasoline for fuel. Some natives work there.

One day, a native walked us along a dirt road bordering a coffee plantation where he worked in the fields. He enjoyed the work.

The Times reporter writes that people are leaving this town. But it’s not fleeing terror. It’s about bettering themselves. “Somebody came and tricked people and told them, ‘I will get you political asylum—and take a child with you,’” a man says. “It’s a new tactic, and people believe it because of their poverty.” He told the reporter the journey probably cost $5,000 to $10,000.

“Poverty?” It could be that there is only poverty if you look at it from the western perspective. The Mayans I knew were healthy. They grew what they ate. They raised and slaughter livestock. Every evening you could smell things cooking.

For a thousand years, the Mayans, healthy then and healthy today, lived as they wanted. Leave them be. I saw it myself. And when I was there we had missionaries on the beach singing to save the souls of these “poor starving malnourished native people”—who as I saw myself were just fine by any standards other than western civilization standards. No jobs! Gotta throw money at these people! Get them working for a dollar a day making hats for us!

The reporter doesn’t mention any current-day turmoil, but does mention the civil war between 1960 and 1990 where Communists were up in the mountains and Westerners were in the big city, and they fought battles. The villagers, caught in the middle, were helpless in this crossfire. But that ended in 1990. There was also a terrible earthquake that shattered many homes in the 1980s. “Mayan communities like theirs have endured centuries of inequality, poverty and repression,” the reporter writes. I thought they liked how they lived.

Our great silver planes continue to fly over. Should we parachute stuff down? I ask, what the hell are we doing there? We have started world wars, a holocaust with gas ovens, global warming that has given us ever-worse hurricanes, tsunamis and floods. And our culture is doing just so great we have to help them? Maybe we should ask them to help us.

The media is also writing stories about the wealthy of Miami now moving to higher ground to avoid the flooding overtaking the coastal roads of that community. Unfortunately, high ground is where the lower middle class lives. Well, they’ll have to move.

Many scientists say that, in the generations to come, we will all have to live like the indigenous peoples on the planet. Maybe we’ll come to like it, too.

No video games, no airports and travel, no frozen food from New Zealand. Just the warmth of family and a belief in God. Or gods.