1859: When Locals Met with Shinnecocks to Rearrange an Agreement

In 1859, a group of Southampton businessmen and farmers formed a group called the Proprietors of the Trustees of the Common Lands of Southampton, intending to cut a deal with the Shinnecock Indians that would result in the Shinnecocks giving up a majority part of their land. These Indians, back in 1705, before the Revolution, had signed a thousand-year lease with the local white men of that era for nearly 3,500 acres of Shinnecock. This property extended from Peconic Bay on the north to Shinnecock Bay in the south.

As such, as seen from another perspective, it completely blocked any attempt to build a railroad out from western Long Island to Southampton and East Hampton Towns farther east. The proprietors would have liked to buy the land to get the Shinnecocks off—many other parcels up-island were bought out for railroad rights of way—but the Shinnecocks didn’t own it, they just leased it. So the proprietors put together a plan. They’d split Shinnecock.

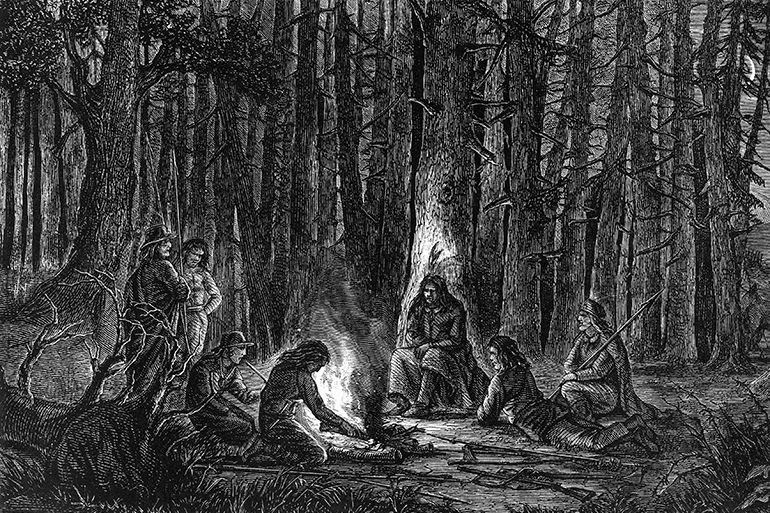

The railroad would come through either one or the other, with the price of adjacent land skyrocketing because of the commerce a railroad always brought. Let the Shinnecocks have the one part, in the form of an ownership deed. They’d take over the other. And the thousand-year lease would be broken. All they needed were the Shinnecock’s approval and the state’s blessing. And so, on a sunny day in 1859, three of their number—two ship captains and a businessman—entered the Shinnecock property looking for Indians they could sign onboard. The men sent were Captain Louis Scott, Captain Jeter Rose and Austin Rose.

At the time, there were about 100 Shinnecocks on that property. The majority of them lived on the peninsula, clamming and fishing, or working for the white men in the Village of Southampton nearby. The northern part of Shinnecock was where the Indians chopped wood, hunted and grazed their livestock. But some lived there, too.

Here was the deal. You have a lease on all the acreage, but some day you will have to give it up. What if I could arrange for you to own it instead? Not all of it, to be sure. The people I represent want the northern half of it. You keep the south, and now you’ll have a deed for it, the whole peninsula. We’ll have the rest. The agent showed the Indians the petition.

In several days on the tribal land, the agents collected a total of 21 Shinnecock signatures. The proprietors felt that was enough.

“It is certainly of vital interest that this road be constructed,” wrote The Sag Harbor Express in 1859. “With the inauguration of this road, our property will be doubled in value.”

The request for this land swap, as they called it, was sent, signed by the proprietors and the 21 Shinnecocks, to Albany for approval.

Three days later, Albany received a second request. This was produced by a local lawyer who represented the Shinnecocks. It said that the first petition was illegal. Specifically, it said that several of the names were forged after the Indians said they wouldn’t sign. Some Indians who signed it were deceased. At least one Shinnecock’s name appeared twice. And this Shinnecock, James L. Cuffee, claimed he had not signed it either time.

The court ignored this second petition. Instead, it granted the first petition to go ahead. The Shinnecocks got the peninsula, which was 350 acres. The corporation got the rest, 3,150 acres of rolling land in northern Shinnecock. Two years later, the proprietors sold this property to railroad executives, mostly millionaires from Manhattan who wanted their railroad to go through. The price for the total was $6,726—about $2 an acre—for all of the land and a right-of-way for the railroad to bring its tracks through not just to Southampton, but farther east to Bridgehampton and thence to Sag Harbor. Soon parcels adjacent to the right-of-way were selling for 10 times that amount. All that remained now were to build the tracks.

But then the Civil War started, and all these projects were put on hold.

In 1863, in the middle of the Civil War, a young Manhattan physician of means by the name of Theodore Guillard Thomas and his wife went by horse and wagon out to visit the farms and rural villages of Long Island. Their trip lasted eight days. The couple spent their first two nights in Babylon, at a rooming house, then pressed on to Quogue, Southampton, East Hampton and Montauk, finally spending a night out at the lighthouse with the keeper and his family.

During this sojourn, the couple fell in love with the simple, bucolic communities of eastern Long Island, and, after returning to Manhattan, vowed that sometime in the future they would return with some friends to hopefully establish a summer colony there. The couple had become charmed by the farmland that went down to the ocean, the single main streets with the Presbyterian churches, the blacksmith shops, feed stores and dry goods stores that marked what were essentially old New England communities. Thomas did take note of a small summer colony of well-to-do Brooklyn fishermen in Quogue when he spent the night there, but there was nothing further east.

In 1870, with the war over, the tracks were laid and the first trains began to move out into the Hamptons. The Shinnecocks watched the trains come through, mostly on their way to the prosperous waterfront town of Sag Harbor. Often sparks from the smokestack caused brush fires, which had to be extinguished.

And then, six years later, the first summer family arrived, bought oceanfront property and built a large summer home by the sea. This family was that of the aforementioned Dr. Thomas. They are today considered the founders of the social set summer colony in the Hamptons. Soon the Thomases were inviting many of their friends to come visit. It was only three hours by train. Thomas would have his servant meet the new arrivals at the train station in a horse-drawn carriage. Luggage would go in the back. During the weekend, Dr. Thomas talked about Southampton and the healthy fresh sea air and urged his New York City friends to do what he had done—build their own home there.

Within four years, many had done just that. By 1880, there were 30 summer mansions where five years earlier there had been none. In Manhattan, Dr. Thomas and others met in a Fifth Avenue apartment to found what was then called the Southampton Village Improvement Association, to “beautify the principal streets” and “see to the removal of nuisances” so as to make Southampton even more attractive to possible future summer residents. They lined both sides of Main Street with 190 trees.

The induced a dry goods merchant to clean up his yard. They put up $25 to get a man who ran an unsightly blacksmith shop to move it to a side street. And they made it a goal to have the community pick up after itself. “It is earnestly hoped,” they wrote in the minutes of one of their meetings, “that especial care will be taken to keep rubbish, paper, straw, old cans and all kinds of litter out of the road.”

A number of local Indians and some of the residents of the local community were happy to have the social set of Manhattan building their great mansions out in Southampton. Having them in town meant jobs and prosperity. But the summer people did want the place neatened up.

During the next 15 years, Dr. Thomas and the others saw to the creation of just about all the major downtown Southampton institutions we have today: St. Andrews Dune Church, the Shinnecock Golf Club, the Meadow Club, the Southampton Beach Club, the Southampton Arts Center (formerly the Parrish Art Museum) and much else. They built their mansions not only down on the ocean but on all sides of Village Pond, which they renamed Lake Agawam, letting it be known they considered it private, their summer centerpiece.

They would take care of it and attend to it without interference. “Not a weed or leaf that floats on its surface escapes our notice the new president of the Southampton Village Association, Salon Wales, told the membership at one meeting. “We should watch it as we would a precious jewel.”

Thus did Southampton and the newly named Long Island Rail Road prosper on eastern Long Island. As for the Shinnecocks, even today, they feel their land was taken from them. Perhaps it was.