Wall Street: What the Great Dutch Wall Can Tell Us About Immigration

Some folks say that walls such as Trump wants to build are not what true Americans put up. But it isn’t true. For nearly half a century there was a “keep out” wall, 20 feet high and running across the northern border of the entire settlement of what is now Manhattan from the East River to the Hudson River. And it was put there to keep the Dutch-speaking settlers behind it safe from those on the other side of the wall who did not speak Dutch.

In that sense it was intended to serve the same function as the one that Trump wants to build today: English-speaking Americans on one side safe from hordes of foreign non-Americans speaking in other tongues.

Many people today think the old Dutch Wall was built to keep the Native American Indians from coming down from the woods in the north. But that was not the case. It was the English that the Dutch wanted to keep out. And when the test came to see if the wall worked, it failed. Maybe there are lessons to be learned.

The wall was built of dirt, boulders and wood planks in 1653, the same year that the Dutch formally chartered the southern tip of Manhattan as the City of Nieuw Amsterdam. A dirt road ran atop the wall, passing alongside five parapets, evenly spaced, which rose up another 10 feet to 30 or more so guards could look down on those approaching below. Between two of these parapets, there were enormous wooden gates that, for the most part, remained open to allow all sorts of people from all over the world—Fijians, Chinese, natives, French and Spanish—to pass in and out. Once inside, visitors walked or rode for nearly a mile down a grand boulevard called Broadway to the southern tip of the community, to a strong Dutch fort and the docks. The place was a trading post, and everybody who came down from the woods to the north of the wall was welcome regardless of race, religion or creed to do business. Unless you were English.

While businessmen grew Nieuw Amsterdam between 1611 and 1654, the English were settling in New England at Providence, Hartford, Boston and New Haven. According to city records kept in Nieuw Amsterdam, the English were “amassing troops in New England for either defense or attack, which is unknown to us.” Fear gripped the thousand or so Dutchmen and their families. And so, this wall was ordered built. Everyone pitched in, and four months later it was complete. The doors would slam shut if the lookouts saw the British approaching.

Defenses at the wall, besides the road atop it, included a palisade along its inner side, nine feet up, ditches filled with water on the outside, cannons on the parapets and more cannons at its edges facing out into the Hudson and East River. Several more cannons were along both shores and down to the Fort at the tip. The town was prepared to meet an attack from anywhere, but mostly at the wall facing north. The only thing missing were lots of soldiers. There were only a dozen or so. Other men with weapons were policemen and custom inspectors.

Sure enough, in 1664, just 10 years after the wall was constructed, the word came down that King Charles II of England had deeded all the land from Maine to Delaware to his brother the Duke of York, and that four British men-o-war with redcoats onboard were on their way to Nieuw Amsterdam. Residents hurried to reinforce the wall. Surely the British would land in the woods to the north of the wall and march down Broadway toward those gates.

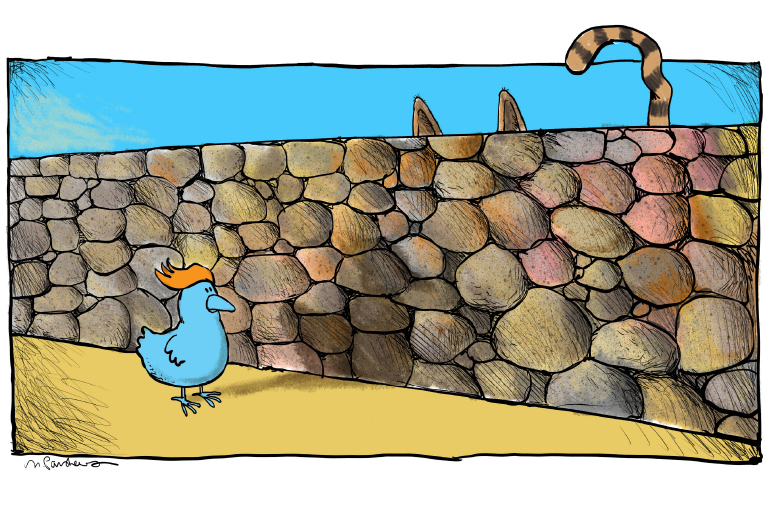

But that’s not what happened. The British ships sailed down the East River in a single line, past the great wall, and dropped anchor with their heavy guns facing directly opposite the town further down near the few side cannons on the shore. The wall had been useless. The English went around it. If you fire, we will fire, was the threat. Some Dutchmen under a white flag rowed out to the ships.

And there they met an admiral who had an offer for the Dutch governor of the town, Peter Stuyvesant. The ships would take the town peacefully and allow the Dutch merchants to run it and enforce their laws and traditions and continue with their multicultural activities as before, except the Dutch flag would come down and the English flag would go up. Otherwise war would break out and the town would burn. Stuyvesant met with his council for an hour or two, and then decided to accept the offer. He surrendered Nieuw Amsterdam without a fight, to save lives. And with that, it became New York City.

Would a Trump wall keep out the drug dealers, rapists, sex traffickers and bandits from south of the border? Well, those folks can fly small planes over it or sail in yachts around it or sneak boxes of the bad stuff under floorboards at the gates to bring it in. The wall might stop some of this. But more likely, in the end, it would remain in place, dazzling in the sun forever unchallenged—as did the Dutch Wall across Nieuw Amsterdam until 1699, when, finally, the British tore it down and replaced it with that same road that used to be up top. They called it Wall Street. And there it continued, crossing Manhattan from the East River to Greenwich Street, where the island ended at the Hudson River. Later it was shortened to end at Trinity Church. Today, west of Greenwich Street is built on fill. And everyone is proud of it. The end.