Danny Peary Talks to 'Depraved' Director Larry Fessenden and His Four Stars

I wasn’t able to see any other films at last week’s second annual What the Fest!? genre film festival at the IFC Center in New York City, but I am confident in assuming there were none better than Larry Fessenden’s Depraved, which sold out on opening night.

A clever, provocative, terrifically acted and written modern-telling of Frankenstein, it is the cult director-writer-producer-editor-actor’s best film in a long career that includes the prize-winning art-horror trilogy Habit, Wendigo, and—about another scientist doing diabolical experiments—No Telling). I especially appreciated how Fessenden exhibits respect for Mary Shelley’s source novel and the classic horror films it spawned, yet injects 21st century ideas and issues into the story in startling ways without angering don’t-change-a-thing traditionalists like me.

You may know Fessenden from his supporting roles for directors Martin Scorsese, Ti West, Neil Jordan, and Jim Jarmusch, and appearances in numerous horror films. You may not know that since 1985, his Glass Eye Pix has released an impressive array of low-budget films of all genres, including Kelly Reichardt’s Wendy and Lucy and Ti West’s The House of the Devil and The Innkeepers. A horror fan since he was a boy, Fessenden, who has “made it my mission to breathe new life” into Universal Studios’ classic monster movies, wanted to update Frankenstein in order “to pay tribute and respond to one of the great icons of cinematic horror, to analyze where Western culture has succumbed to narcissism and collapse, and to tell a personal story of being alienated simply by being conscious in an indifferent and arbitrary world.”

Having wanted to tackle the Frankenstein story since 2003, he finally “decided in December 2017 to mount a no-budget version of the film by committing to a location and starting to build a set. I figured if I couldn’t raise the money, I would only lose the cost of the rental on the space [in Brooklyn] and the supplies to make the wall of windows that would play as our industrial loft. I liked to joke that I built my wall before Trump built his.”

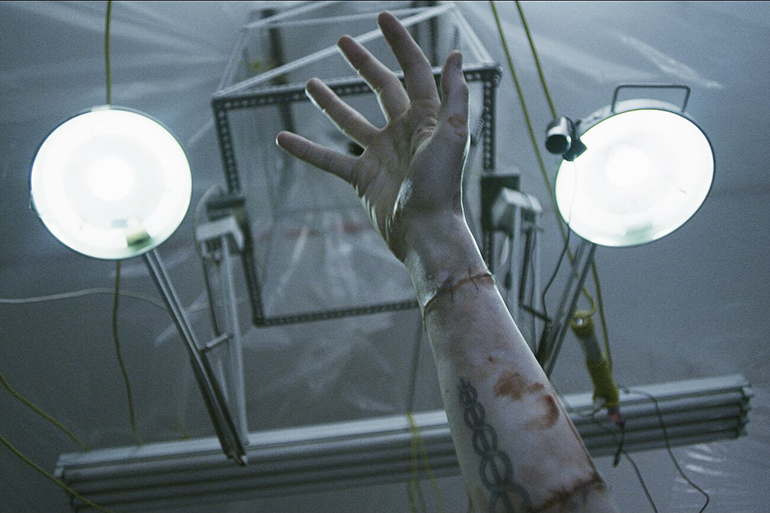

The (slightly edited) synopsis in the press notes: Alex (Owen Campbell) leaves his girlfriend Lucy (Chloë Levine) after an emotional night, walking the streets alone to get home. From out of nowhere, he is stabbed in a frenzied attack, the life draining out of him. He awakes to find he is the brain in a body he does not recognize. The creature, Adam (Alex Breaux), has been brought into consciousness by Henry (David Call), a brilliant field surgeon suffering from PTSD after two tours in the Mideast, and his accomplice Polidori (Joshua Leonard), a predator who married their rich classmate Georgina (Maria Dizzia) and is determined to cash in on the experiment that brought Adam to life.

After teaching his strong and smart but innocent creation things that will help him integrate into society—except about the birds and the bees–Henry is increasingly consumed with remorse over what he’s done. Only Liz (Ana Kayne), Henry’s estranged girlfriend, reaches out to consider the creature’s loneliness. But that can’t save him: when Adam discovers his own origin, he goes on a rampage that reverberates through the group and tragedy befalls them all.

The Teaser Trailer:

Last week at the B Bar & Grill in Manhattan, I had this free-wheeling conversation with Fessenden (who doesn’t appear in the film) and its four major stars: David Call (Tiny Furniture), Alex Breaux (Ana Duvernay’s upcoming Netflix miniseries Central Park Five), Joshua Leonard (Blair Witch Project, Unsane) and Ana Kayne (Another Earth, NBC’s new series The Enemy Within) about Depraved and its significant themes and characters.

Danny Peary: Larry, I read in the press notes that there was an audition involved in regard to Alex playing Adam. That surprised me because I assumed while watching Depraved that all your actors knew you and each other from the indie scene.

Larry Fessenden: That’s good! It wasn’t that we were a team, but we discovered that most of the people who worked on this film did know each other to some degree. For instance, it turned out that David had been in Behold My Heart [2018], the last film Joshua directed.

Ana Kayne: I knew David and Chadd Harbold [who co-produced the film with Fessender and Jenn Wexler].

Joshua Leonard: This was the second time that Maria Dizzia played my partner in a movie.

DP: All of you are not just actors but writers, producers and directors, so was there an instant community?

David Call: We came from the same background and worked with a lot of the same people over the years, so we were sort of on the same page. It was a really good group of collaborative folks.

JL: Larry set the tone for a good collaborative environment and there was a lot of camaraderie on the set.

DC (joking): And one of us—Alex [who has acted On- and Off-Broadway]—was highly trained.

DP: Larry, I read that when you were young you got hooked watching Universal horror films? Me too. I was eight when Universal sold all those films to television and I’d watch them one by one and not sleep at night. They changed my life and though you saw them more than a decade later, I think it changed yours, too.

LF: I appreciate your bringing that up because that’s exactly what happened. Until Universal sold its movies, its monsters [the Frankenstein monster, Dracula, the Wolf Man, the Mummy and the Invisible Man] had fallen out of vogue. But suddenly a whole new generation of kids started watching them and that led to the Aurora Monster Models kits and fanzines like Famous Monsters of Filmland. It was actually a cultural phenomenon and kids my age grew up on those monsters.

It made a real imprint on me. That’s why I grew up with Frankenstein and can still relate to it. Of course, they’ve always made new versions since the original in 1931 [which was directed by James Whale and starred Colin Clive as the Doctor, and Boris Karloff as The Monster]. For me, the version starring Michael Sarrazin [a 1973 TV-movie titled Frankenstein: The True Story] was very striking because the Monster was humanized. He actually starts out very handsome and then he slowly decays. That made an impression on me.

DP: So, Alex, when you saw that Larry chose to put in the credits that you play The Monster, rather than Adam, did you think Larry should have put the character in quotes, as “The Monster,” or had you decided he is a monster? That’s the big question people have been asking for almost 90 years.

Alex Breaux: You’re talking about self-definition versus outside perception. My character is perceived by other people as a monster or creature, and he is referred to as that. However, our film is psychological in nature and I think Adam is living within himself and doesn’t understand the “Monster” concept.

DP: The poster for the 1931 film proclaimed FRANKENSTEIN: THE MAN WHO MADE A MONSTER. So the character was always called a monster, even though there was some question about who really is the monster of the story. I don’t think Karloff, who got the role when Bela Lugosi turned it down, objected to his character being called The Monster, but a theme of both James Whale films in which he played the role, Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein, and Larry’s horror movies, is that our world has human monsters.

AB: In the script, the character’s name is Adam. That’s the name given to him by his creator, Henry, David’s character. I treated the first half of the film as an accelerated coming-of-age film, where Adam’s creator and father figure tries to build up his confidence and improve his behavior and capacity to integrate into society. I see that as an earnest movement forward by The Monster, even though it’s motivated by Big Pharma and Polidori for more cynical reasons that he’s not aware of.

DP: Larry mentioned Michael Sarrazin’s Monster being handsome at first. Alex, if your character Adam were handsome and have no stitches all over his body, would anyone think him a monster and shun or fear him?

AB: I feel Frankenstein as a parable about discrimination against a minority. What are the differences people pick out that relegates one to the in-group or out-group? What makes Adam a monster is that he’s not human because he’s been assembled from all these human parts. That makes him different.

DP: There’s an adage in horror: If you look like a monster, you will act like a monster.

DC: I think Henry’s whole journey is to recognize Adam’s humanity. In Henry’s mind for most of the film, Adam is not a monster but an experiment or a project not unlike a car that he’s building in his garage. I don’t think he views his creation as a monster or as a person, but as a thing or object he’s made that he wants to work and then work better and better. Only as the film goes on does he begin to recognize Adam is something more. It’s like “Oh, this is a person. I made a person. Uh, oh.”

DP: Larry, do you think Henry would have done this experiment to bring a dead person back to life if he weren’t suffering from PTSD after being unable to keep some injured soldiers alive on the battlefield?

LF: I wanted to show that society thrust him into an impossible situation by sending him on a dubious mission. I’m saying society has let down our soldiers who fought honorably and were there to save lives. As a medic, Henry did try to save lives but felt guilty that he couldn’t bring back to life those who died. He came back haunted by that and that’s why he says he wants to right a wrong. But who takes advantage of that is his friend Polidori, an enabler.

DP: One of the most important lines in the movie is two words long. It’s Henry saying to Adam, “I’m your…” He stops himself from saying more. David, what doesn’t your character say?

DC: I don’t think he knows what to say. Is it “creator?” Or “builder?” Or, since he’s kind of a human being, “father?”

LF: Henry’s whole journey is his coming to realize that he is his father. At a key moment late the film, Henry has a memory of them being together as, he probably views it, father and son.

DP: In the first scene of the movie, Alex and Lucy argue about his unwillingness to have a child with her and whether he could be a good father. Why was it essential for that to be what their conversation is about?

LF: Because the whole movie is about parenthood. Polidori says to Adam, “I don’t suppose Henry has had time to teach you anything.” Yet Henry has taught him music, how to solve puzzles, and how to play ping pong. But Polidori has his own idea of how to present the world to Adam, first with high art at the Met and then a strip club.

DP: Polidori also teaches him pool, which is much more of a vice than ping pong.

LF: Exactly. There are puzzles and games all the time throughout the movie. Even Shelley [Addison Timlin], the woman Adam meets in the bar, is solving a puzzle. The human mind is always trying to solve problems, actually our emotional and spiritual ones. That’s the idea there.

DP: Larry, you won’t mind my disagreeing with something you wrote in the press notes: “In most versions of the story, the doctor is repulsed by the creature.” I think Frankenstein always sees his creation as a beautiful masterpiece. He is never repulsed by its looks. He is, however, horrified by its violent, cold-blooded acts, which are like a slap in his face and shock him back to his senses.

LF: Maybe you’re right, but there is a scene in Mary Shelley’s book and in most of the movies in which Frankenstein rushes into his bedroom and collapses out of despair, and the Monster comes in and parts the curtains. In the original story, that’s the seminal moment—he rejects the creature and the creature leaves. Maybe I played too loosely with the word “repulsed.” but the point is that he does reject the creature in the traditional sense. In my film, it’s played more subtly with Henry slowly becoming more confounded and disappointed in his creation—that’s his form of rejection.

DC: I don’t know that he’s so much repulsed by the creature as what the creature represents. The creature is a physical representation of Henry’s own hubris and lack of a conscience. As I said, The Monster is his work, his experiment, and when Henry is forced to confront his creation’s humanity he’s also is forced to confront his own inhumanity. I think he’s more disgusted with himself than with the creature specifically.

DP: Larry, in the scene from the novel and some films that you described, I believe The Monster opens the curtains in order to bring God’s sunshine back into Frankenstein’s dark, secretive world, which has been absent since the crazed scientist started playing God himself. Frankenstein realizes he has committed blasphemy by usurping God’s creator role. Your modern-day film, however, doesn’t bring God into the conversation.

LF: I believe strongly that this is an existential Frankenstein movie. It’s precisely dealing with the idea that if there is no God and we are the masters of our destiny, then the ways we make decisions, handle technology, and address the issues of life and death are actually done in our names. This movie very specifically takes the initial premise from the great versions of Frankenstein but then moves away from our accepting the God-servant role and says we are in fact the gods. It presumes that.

Also, to me, one of the big little moments in the movie is during the scene in which Polidori takes Adam to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Adam listens to Polidori speaking about morality in different ways and how humans are narcissistic and depraved, but there is one moment when Adam is looking at a painting of Christ and he is really drawn into it. We linger on that for a moment but Polidori just walks by without saying anything.

This takes place pretty much at the center point of the movie and my idea is that The Monster is drawn to that image of Christ and may be asking himself a spiritual question like “Why is this a powerful picture?” Yet Polidori just ignores it, because in a sense we’re in a godless time in our history. Polidori had a line about the image that was a little preachy in which he says, “Never has humanity wasted more time on something,” but I preferred having Polidori not think the painting is worth mentioning and so just keeps walking.

DP: Joshua, John Polidori is not in the opening of Bride of Frankenstein, although historically he actually was present when Mary Shelley, Percy Shelley and Lord Byron challenged each other to write the best horror story. In fact, he’d write the first vampire story. But Larry references Faust by making him a manipulative Mephistopheles figure in Depraved, a terrific villain who is, I believe, trying to corrupt an innocent. Is that the approach you took?

JH: No. I certainly didn’t approach it with Polidori having the motivation to corrupt a soul. To me, it was far less calculated and far more tragic than that. It had so much less to do with his intentions regarding anyone else than his desire for self-preservation and the notion that he can’t do much on his own. Polidori feels the need to align himself with people who are smarter and richer because he has so little of substance that he can offer himself.

DP: An elitist villain for our times.

JH: Yes. We talked a bit about how he represents the capitalistic id of America. There was a lot of media about Martin Scarelli at the time we were making the film. And that guy [who increased the price of a vital HIV drug by 50 times] was a fascinating creature to me because of how unapologetic he was about being a monster and yet when you watched him you saw this entirely broken human being.

DP: Making Polidori a villain, essentially taking the place of Ernest Thesiger’s memorable Dr. Pretorius in Bride of Frankenstein, was one of Larry’s big changes to the Frankenstein story. Another major difference is the role of the primary female character, who is Elizabeth in the novel and two 30s movies, and Liz in Depraved. The major change is that while Elizabeth is not privy to what her obsessed man Frankenstein is doing behind closed doors, Liz knows of Henry’s unnatural experiment and, though reluctant, she is complicit in his crimes. So, Ana, was it interesting to you that the role of the character was being changed so radically?

AK: I actually wasn’t familiar with how the character has been viewed. I didn’t know about changes and just embraced what was on the page.

DP: What does she see in Adam that makes her be the only one to treat him warmly, as a human being?

AK: She is attracted to his isolation and loneliness. And she innately wants to take care of this obviously unwell creature. I’m just making this up right now, but I think there’s a tenderness and vulnerability that she sees in Adam that isn’t present in Henry, and she finds that beautiful and attractive and that escalates to… I’m not sure what.

DP: His innocence and honesty also must appeal to her.

AK: Yeah, she’s not really finding that in her primary relationship, and this nether creature is living in this place of vulnerability.

DP: You spoke of her innate desire to take care of him. Do her innate qualities include a desire to act as his mother would or act like a girlfriend?

AK: I think both. Although my original impression was that she doesn’t have sexual feelings toward him and that she feels strictly a mothering thing. He is so lonely that her feelings move toward a slightly sexual thing, but I think for her it’s more curiosity than a desperate need for connection. It can be interpreted as sexual, but I didn’t come from that place.

LF: One thing you mentioned is important. She is complicit. She goes to Henry, “You mean you really did it?” That means he has been talking about creating someone from the parts of dead bodies for the longest time. Liz and Henry drifted apart perhaps, but there is a sense that she knew what he was up to all along. The same with Polidori’s wife, Georgina. Before they see the creature moving about, the two women may not have entirely believed it’s possible to create a living being from dead people’s body parts, but they knew what Henry and Polidori were up to.

The other thing I’d like to say is that Liz is supposed to be the conscience of the movie. Everyone else is behaving very selfishly. And in her backstory we get snippets of who she is. She is someone who chooses to work at the Veterans Hospital and tries to help people. Henry tells her, “You can’t solve everything with kindness.” But we get the impression that kindness is what she does put out into the world. Even when it becomes slightly sexual with Adam, her allowing him to “explore” is another act of generosity.

DP: One of the interesting questions about the two Karloff films is: Does anyone feel guilty about the murders The Monster commits? In the two Karloff films, it’s not clear if The Monster ever feels guilt for murdering people. At the end of Bride, he sends Henry and Elizabeth to safety and stays behind to die with the Bride and evil Pretorius. But even then we don’t know if The Monster knows he has done wrong or just realizes that he is an abomination who doesn’t belong in this world.

AB: I think he feels not so much guilt as confusion. He has an internal logic. When he ends up hurting the woman he meets at the bar, he assumes that Henry can perform the same magic he did on him and put her back together again. When Henry yells at him, “It doesn’t work that way!,” it starts dawning on him that he should feel guilty about something, that he misinterpreted the logic of the reality he is living in.

LF: He gives something of Alex’s back to his girlfriend, Lucy, who’d given it to Alex on the night of his slaying, because he figures out that she is the girl he keeps having flashes of in his memory. Then, realizing he caused a lot of deaths, he exiles himself. In a way he does learn a lesson and knows that it’s best if he removes himself and walks away, which, of course, is how it is in the book. In the book, he says he went away on the waves, which too is self-exile. That’s the tragedy of The Monster.

DP: As I said, Henry is horrified by the murders, but perhaps his guilt is not about the deaths themselves, which he blames on The Monster, but about his defiance of God. David, does your character feels guilt of any kind?

DC: Henry feels guilt for sure. But not until The Monster tells him, “I want to have a girl, like you have a girl.” That’s when Henry is confronted with the humanity of this being he has created and the realization that it can never actually have a human life and participate in humanity even though it is in some degree human. That’s where the guilt comes from and why Henry ultimately decides he should kill The Monster.

DP: Ana, does Liz feel guilt?

AK: Definitely. And she takes on Henry’s guilt as well. She didn’t help him create The Monster, but when she makes the switch and becomes complicit in Henry’s attempt to get rid of The Monster, she feels tremendous guilt. That’s what drives her toward madness.

DP: I think Polidori is the one character not to feel any guilt.

JH: It will take Polidori a good 10 years in therapy for him to get to the point where he can even touch on guilt.

DP: To me he exhibits the casualness of evil.

JH: I don’t think it’s so casual. I don’t think he’s a sociopath, I just think he has such a perilously constructed version of who he is in his own brain, and that if you pull one thread it will all fall apart.

LF: My favorite moment is when his rich father-in-law says he doesn’t care about what his company is doing, and Polidori’s whole world drains away.

AB: Polidori is a capitalist and his morality is connected to his survival.

LF: When Polidori tells the angry Monster, “I’ll take care of you,” he’s just groping at straws to survive. He’s feigning remorse.

DP: Did you want all your characters to feel guilt?

LF: It’s a movie where I’m trying to say who accept their own responsibilities and to what degree. So it is a story about accountability and exactly when people will recognize they have it.

DP: Larry, in 2003 you came up with the idea of making this film by writing a one-page synopsis. Is this the film you had in mind back then?

LF: Yes. I like to point out that when I put the edit together—very quickly, because it all went together—I asked myself, “What did I do?” Because I wondered if I didn’t make it scary enough or forgot to do certain things that would make it easier to sell and not let down people who will want it to be another type of film. So while this is absolutely the film I have wanted to make for all these years, I wondered if it is the right movie.

DP: I can say that it is.

Danny Peary has published 25 books on film and sports, including Cult Movies,Jackie Robinson in Quotes, and his newest publication with Hana Ali, Ali on Ali: Why He Said What He Said When He Said It, about the origins of her father’s most famous quotes (Workman Publishing).