‘Popeye’: Comic Book Nirvana

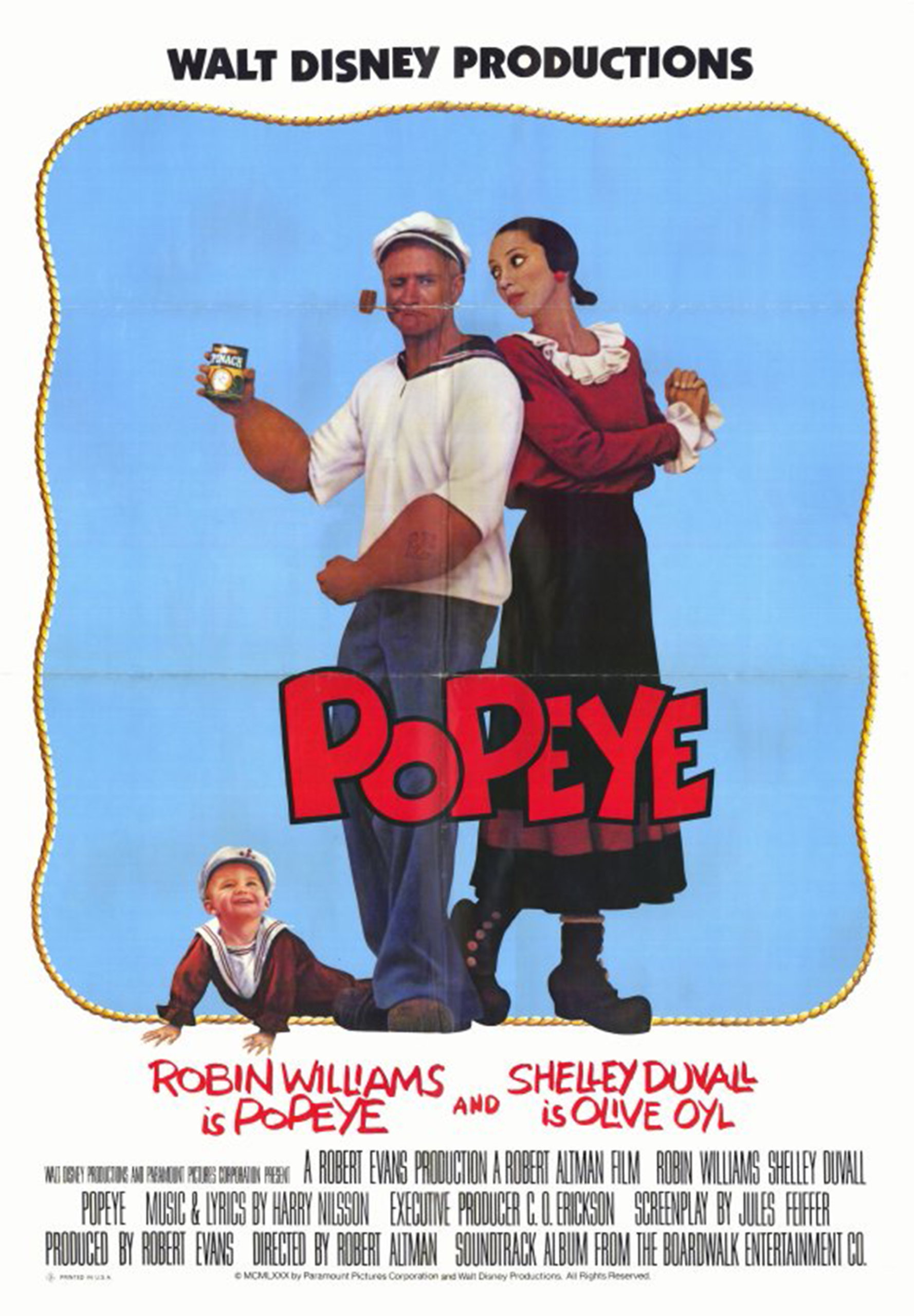

“I yam what I yam, and that’s what I yam.” What better tagline for today’s cultural chaos? Robin Williams’s matter-of-fact boast as Popeye the Sailor Man, the title hero of Robert Altman’s 1980 venture into comic book nirvana, dismisses any doubts or criticisms with a declaration of pure ego.

His manic energy propels the film into a raucous improvisation featuring most of Altman’s troupe of seasoned players plus some brilliant additions — Shelley Duvall (fresh from dramatic success in “The Shining”), Paul Dooley, Ray Walston, Paul Smith, Donald Moffitt, Richard Libertini, Bill Irwin, Linda Hunt, and many others — recreating seamlessly the look and feel of 1930s newspaper comics.

This inspired cast is the reason the film has remained a favorite with audiences and film buffs. Williams had just left his career-sparking multi-year stint as the ad-libbing alien of TV’s “Mork and Mindy.” With Altman’s encouragement, he continued that unpredictable improvisation as Popeye, filling the soundtrack with chuckles, mutterings, song segments, and expletives (as with any Williams performance, you have to listen closely, or more than once, to fully appreciate its many layers). His physical makeup — impossibly huge forearms, balding head, ubiquitous corncob pipe — capture perfectly his cartoon antecedents.

But rivaling Williams is the gangly Duvall as Popeye’s sweetheart Olive Oyl, the role she was born to play. Yes, there are the obvious physical similarities (at one point trying to recapture her balance from a fall she resembles a demented windmill — knees and elbows akimbo, feet splayed in opposite directions — a gem of inspired physical comedy). But in counterpoint she embodies a loving sweetness, both in her courtship scenes with a flummoxed Popeye but also in her unexpected maternal response to the foundling Swee’Pea.

And was there ever a cuter screen infant than Swee’Pea, the year-old baby adopted by Olive and Popeye, in real life, Altman’s grandson! By some miracle, Swee’Pea somehow perfectly reflects the physical characteristics of Williams as Popeye — the bald head, the crooked smile, everything but the pipe and forearms.

The remaining comic cast interacts with each other as an integrated community of eccentric misfits. As with Altman’s townspeople in “McCabe and Mrs. Miller,” all have their own personalities, expressed in relation to each other — murmuring background dialogue punctuated with punchlines, exaggerated make-up and costumes, cartoon-like actions that recall silent-film comedy, such as Bluto (Paul Smith)’s exaggerated slow burn or Bill Irwin’s astonishing physical contortions.

And much as with the evolving frontier set construction of “McCabe and Mrs. Miller,” the slightly cuckoo town of Sweethaven is a character in itself, built from scratch by the brilliant production designer Wolf Krueger, with cartoon streets, docks, and buildings that just barely hang onto the steep seaside cliffs.

For the narrative, Altman turned to Jules Feiffer, the acerbic Village Voice cartoonist turned screenwriter. Feiffer’s background love of cartoon history brings just the right feel to the film. Rather than the frantic pace of the Fleischer Brothers 1940s Popeye movie cartoons (seen on TV in the ‘50s and ‘60s), he defines a sweetly melodic tone that reflects more the original 1930s E.C. Segar Popeye newspaper series. Those four-panel strips engaged running characters in short, quirky, episodic stories that themselves could trace their antecedents to innovative (and never-equaled) creations like George Herriman’s Krazy Kat and Windsor McCay’s Little Nemo.

Altman, ever the maverick, although coming off of a decade of critically successful films including the abovementioned “McCabe and Mrs. Miller” and “The Long Goodbye,” was also on shaky ground with the Hollywood establishment due to his outspoken criticism of the stifling studio system. The film received a mixed reception when released — it had been behind schedule (due in large part to a monsoon that destroyed much of the set), wildly over budget (for the same reason, but also because of Altman’s profligate party-style production), and the subject of pre-release negative press (partially in snarky response to his closing his island of Malta headquarters to reporters).

However, critics and film enthusiasts appreciated its quality, audiences loved its playfulness, and over 30 years later, “Popeye” represents an important benchmark in Altman’s oeuvre and still proves an enjoyable delight.

Streaming is a periodic look at classic films. “Popeye” can be found on streaming channels and apps such as Apple TV and Amazon Prime Video.