Tom Seaver Memories

When I felt the first rumor of spring in the East End air last week as warm breezes blew across the diamonds and high school teams played baseball in Daylight Saving Time, I heard the radio newscaster deliver the tragic news that Tom Seaver, at 74, had developed dementia.

I felt like I just ran over my youth. The cruelest irony is that this legend who has given millions so many “terrific” memories might soon have no memory of them himself.

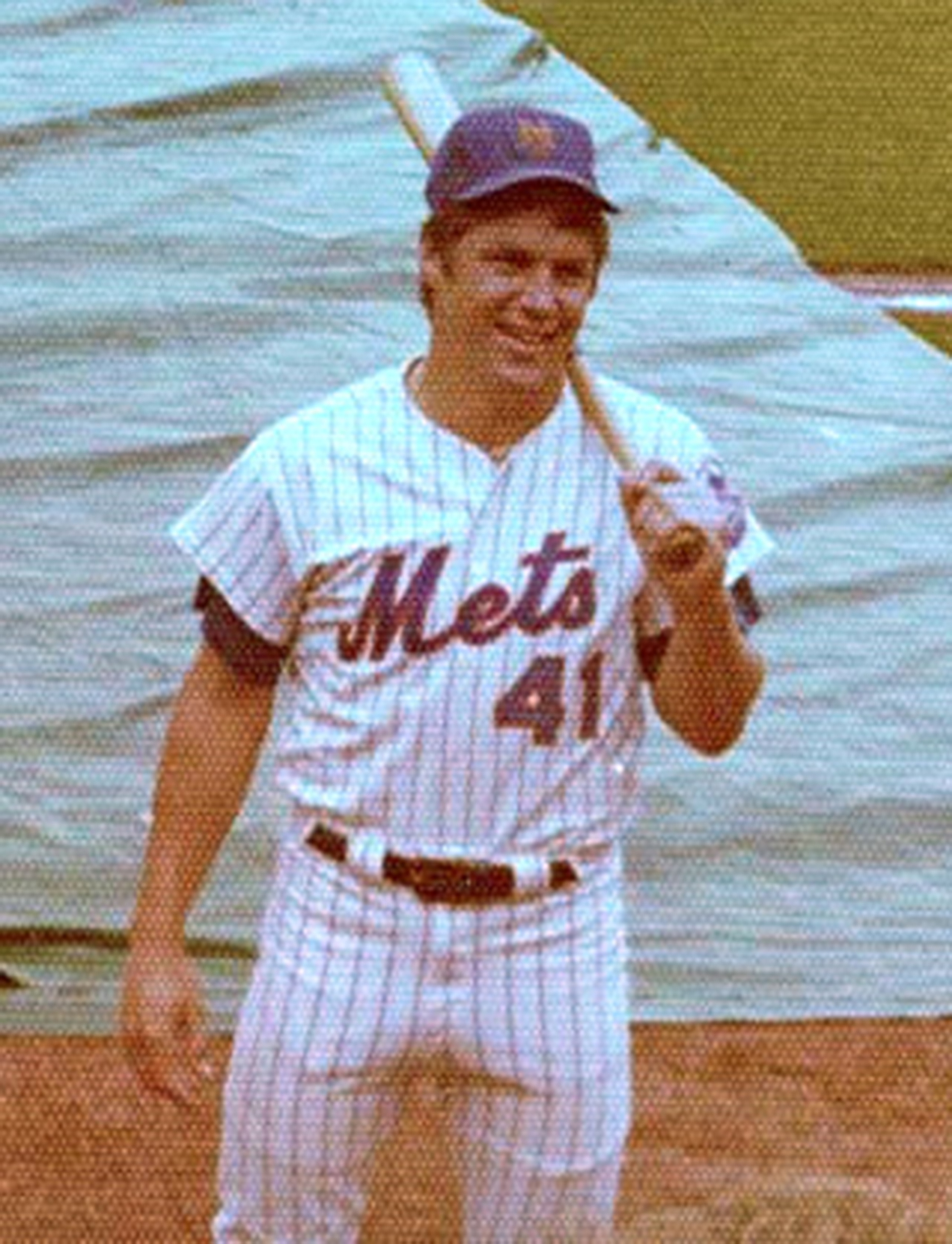

But for those of us who watched #41 walk the first time to a little dirt hill in Queens in 1967, he will never be forgotten.

I had been a Mets fan for five miserable years by the time Tom Seaver came to New York. I grew up in a Brooklyn tenement in that terrible time for New York baseball fans after the Dodgers deserted west to Los Angeles in 1957, with the Giants lamming to San Francisco the following year. I was just a little boy, so my brothers and I grew up thinking there was an archvillain in the world that my father called “Sonuvabitch O’Malley.”

We didn’t know that his real name was Walter O’Malley, owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers, the team my father loved with all his broken heart, because rooting for Dem Bums made that Belfast-Irish immigrant as much an American as his oath of citizenship.

My father watched the reviled Yankees defeat the Dodgers one World Series after another until 1955 when the Dodgers finally brought the championship flag to Brooklyn.

Two years later, the Dodgers moved to California.

Then in 1962 came a brand-new National League team called the New York Metropolitans, and a smile returned to my dad’s face even as the Mets’ first season was an historic 40-120 disaster.

Some of my fondest father-and-son memories were sitting on our pebbly tenement roof next to Babe Caputo’s pigeon coop listening to the Mets find new inventive ways to lose games on a Panasonic transistor radio. Whenever my dad sent me for a pack of Camels in Mr. B’s candy store across the street, the grumpy old Bronx Yankee fan would look up from the baseball standings in the Daily News and say, “You wanna see dem Mets in foist, toin da paper upside down.”

The Mets stayed in the cellar for the next five years.

Then, in 1967, a young guy named George Thomas Seaver from Fresno, CA, came to town, and in two years, he helped hurl the laughingstock Mets from the sub-basement to 1969 World Series champs, which made my amputee father dance like he’d grown back his left leg that he’d lost to gangrene after a soccer injury.

The irony that a kid from California that had hijacked our Dodgers had come to New York to give us a World Series flag was not lost on my old man.

I travelled to the parade through the Canyon of Heroes in Manhattan to cheer Tom “Terrific” Seaver’s Mets the same year Neil Armstrong walked on the moon and Joe Namath spiraled the Jets to the Super Bowl triumph.

Seaver lived in a house in Bayside, Queens, a few miles from Shea Stadium. Kids used to line up with baseballs in the morning and give them to Seaver’s wife, Nancy, and she’d tell them to come back the next day to pick up the autographed balls.

In 2008, I finally met Seaver, when he and Darryl Strawberry visited a firehouse in Maspeth, Queens to say they had not forgotten the 19 men from Squad 288 who had died on September 11, 2001 in the Twin Towers, which rose the same year as Seaver lifted the Mets to a World Series flag.

I took my son Liam, eight, a Little Leaguer, with me on assignment that day, a nervous and wide-eyed kid under his Mets cap. Liam had stayed up late the night before Googling Seaver’s stats. When he met the great Met, Liam said, “I read you won 311 games and had like 3000-and-something strikeouts.”

“Three thousand and something?” Seaver asked, feigning disappointment. “You mean you don’t know exactly?”

Seaver yanked off Liam’s Mets hat, autographing the inside peak with a Sharpie, “3640 K’s! Tom Seaver HOF, ’92.”

Liam asked, “How does it feel to win three Cy Young Awards, Mr. Seaver?”

“Better than a sharp stick in the eye, Liam,” Seaver said. “But not as important as what these firefighters do for us every day. We wanted to let these guys know that we’re in awe of what they do. They’re the real heroes.”

Seaver and Strawberry gazed at the wall honoring Squad 288’s 19 fallen firefighters of 9/11. “No one should ever forget,” said Strawberry.

“I know I never will,” said Seaver.

I remembered Seaver’s departing line in the firehouse in 2008 as I drove down Montauk Highway last week after hearing the terrible news of his mental decline, which was like being beaned by a Seaver fastball.

The unkindest strike of all, of course, is that #41 will not remember the thrilling memories that he gave to millions of baseball lovers, especially Mets fans — including three generations of my family.

Thanks for those memories, Mr. Seaver, and for being so kind to my kid, who will never forget you.

Tom Seaver might not remember, but he will never be forgotten.

denishamill@gmail.com