Tome Tells History Of LI Duck Farming

A striking bit in Susan Van Scoy’s little treatise on “The Big Duck and Eastern Long Island’s Duck Farming Industry” is learning that this once-entrepreneurial local enterprise that began with three ducks and one drake in the 1870s and grew into a nationwide business that at its peak could boast 100 farms on Long Island, serving 70 percent of the country’s ducks, is now down to just Douglas Corwin’s Crescent Duck Farm in Aquebogue.

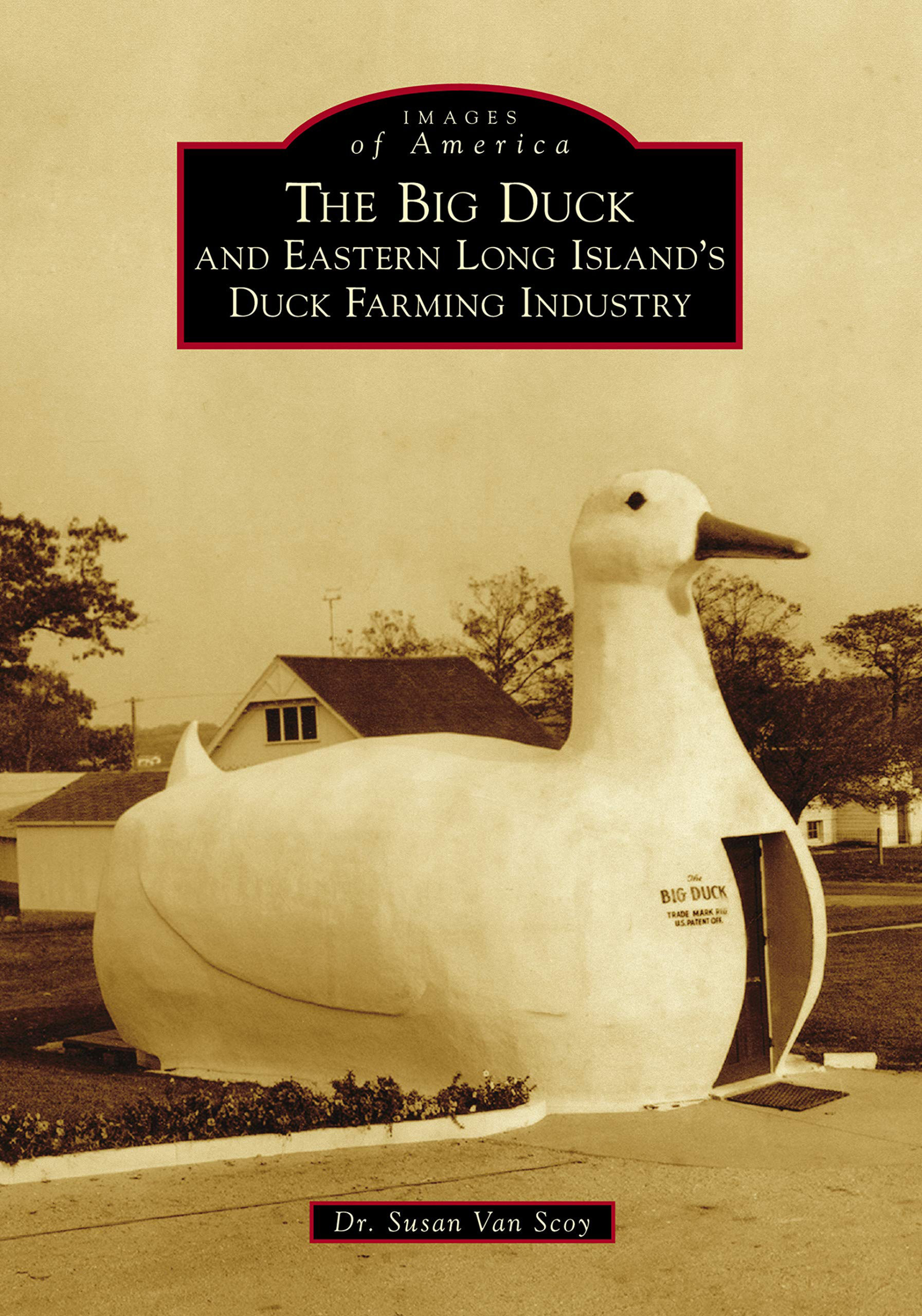

Rather than take this severe drop as a prompt for eulogy, Van Scoy, an art historian who teaches at St. Joseph’s College in Patchogue, uses that fact to celebrate the legacy of Long Island duck farming as part of the East End’s unique history, and to promote one of the area’s most iconic symbols, the 20-foot tall white ferrocement Big Duck, conceived by Martin Maurer in 1931 that, courtesy Saul Steinberg, the famous American cartoonist and illustrator and onetime resident of Amagansett, graced the cover of the May 11, 1987 New Yorker.

Though moved three times over the years, the Big Duck is back on Route 24. It, along with the 13-acre Big Duck Ranch, have both been added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2008 and welcome visitors with a gift shop and community events. These include, as Van Scoy points out, the Rubber Ducky Race in August, various craft fairs and festivals, the annual Big Duck Holiday Lighting on the Wednesday following Thanksgiving, and at Christmas, “duck carols” along with a visit from Santa, escorted by the Flanders Fire Department.

Though the Big Duck has appeared in celebratory articles, it was Van Scoy’s belief that there was no “centralized source” on the subject or, since 1949 (the height of the industry), on the history of duck farming on Long Island. She was also eager to “showcase never-before-seen historical photographs from family collections before they got destroyed or lost.” She felt that the project would appeal not just to those in the arts — artists, art historians, architects — but “to a broader public that includes Long Islanders, local history lovers, environmentalists, farmers, foodies, tourists, children . . . everyone.”

She happily discovered Arcadia Publishing and The History Press, which promotes itself as “the most comprehensive publisher of local and regional content in the country.”

Those of a, ahem, certain age traveling Route 27 on the South Fork might well remember the Water Mill duck farm not far from Duck Walk Vineyards (established 1994). Though the industry was in decline, the farm was still there, with ducks visible slightly uphill on the south side of the highway. And, of course, nostalgia buffs will also recall John Duck, a landmark restaurant originally started by John Westerhoff at the Eastport Inn in 1900 but that his son Ben moved to Southampton (it closed in 2008).

The photos tell it all, and indeed, this is a chronological picture book, with a brief introduction and annotated captions that identify farmers, their families, workers, and breeding and marketing innovations. Readers learn that originally the ducks came from Shanghai and were known as Pekin ducks, a particularly tasty breed that by 1922 was producing two million ducks a year. The peak period was 1940, when approximately 100 duck farms were concentrated between Eastport and Riverhead.

From the start, success in both breeding and marketing was immediate, with a Pekin duck yielding 150 eggs a year. Ducks matured at approximately seven weeks and it took about four weeks to hatch, with ducklings continually transferred to breeding rooms adjusted for temperature and water supply (ducks have to learn how to swim). What Van Scoy’s introduction euphemistically calls “the day of reckoning” took place at approximately 12 weeks, by way of a knife to the jugular as the duck hung upside down. (In the text-enhanced photos, the phrase becomes “duck killing.”)

By the late 1920s, modernization was under way, including electric incubators, improved feed, water pumps, radiant-heated floors, and germicidal lamps. And then, by mid-century, a number of adverse factors started kicking in: overproduction, environmental concerns, fires, and new state regulations, including demand for waste water treatment, lowered prices after spring, not to mention changes in eating habits.

Many farmers sold out to real estate developers. Keeping a duck farm was always hard work, especially for the women who picked the feathers by hand. By the 1960s, only 48 farms were left; by 1974, 27. The Big Duck knows more and would enjoy a visit.

A portion of the proceeds from the sale of the book will be donated to the Friends of the Big Duck, which sponsors the various programs. An author talk and book signing will be held on Tuesday, April 2, at 7:30 PM at the David W. Crohan Community Center, located at 655 Flanders Road.