Henri Dauman: Behind The Lens

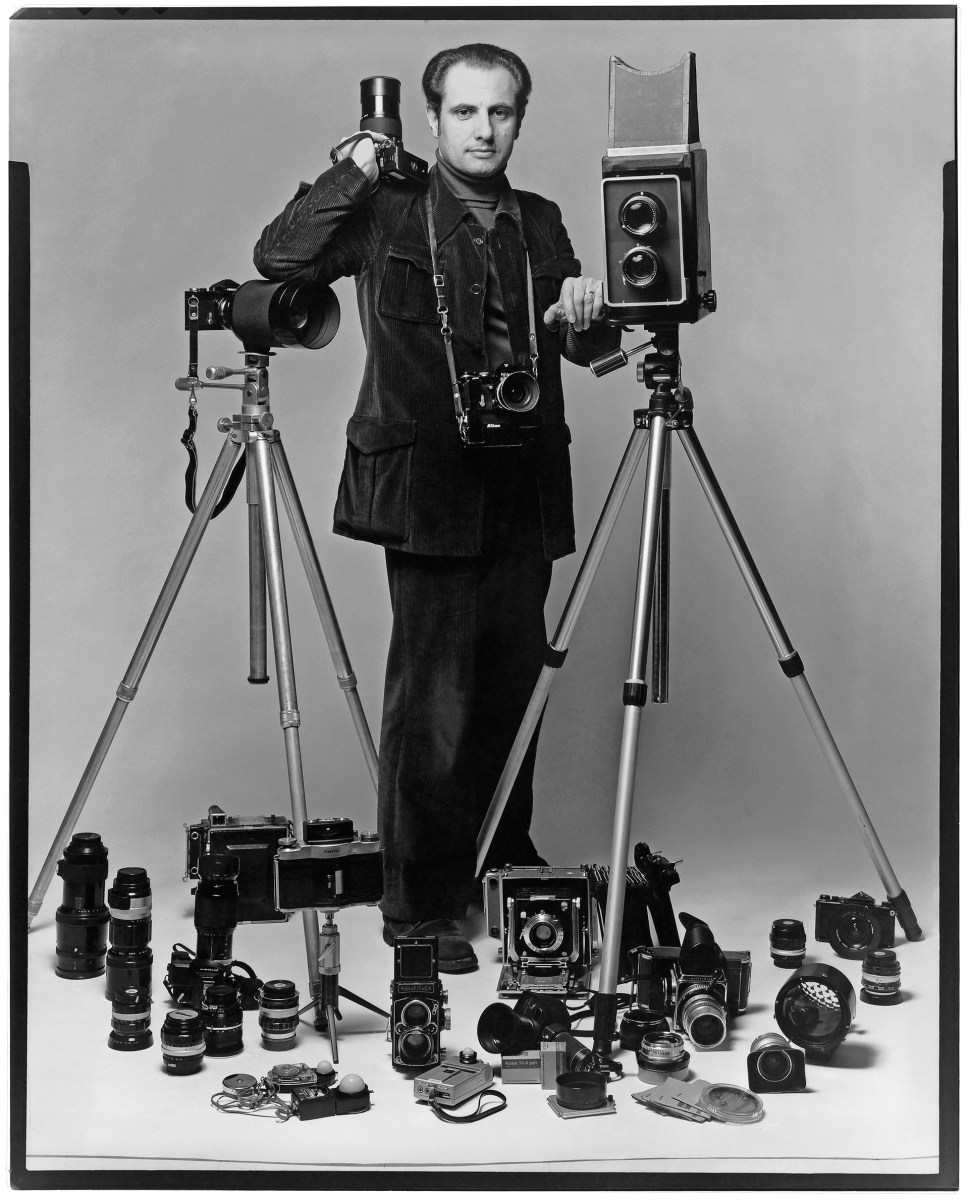

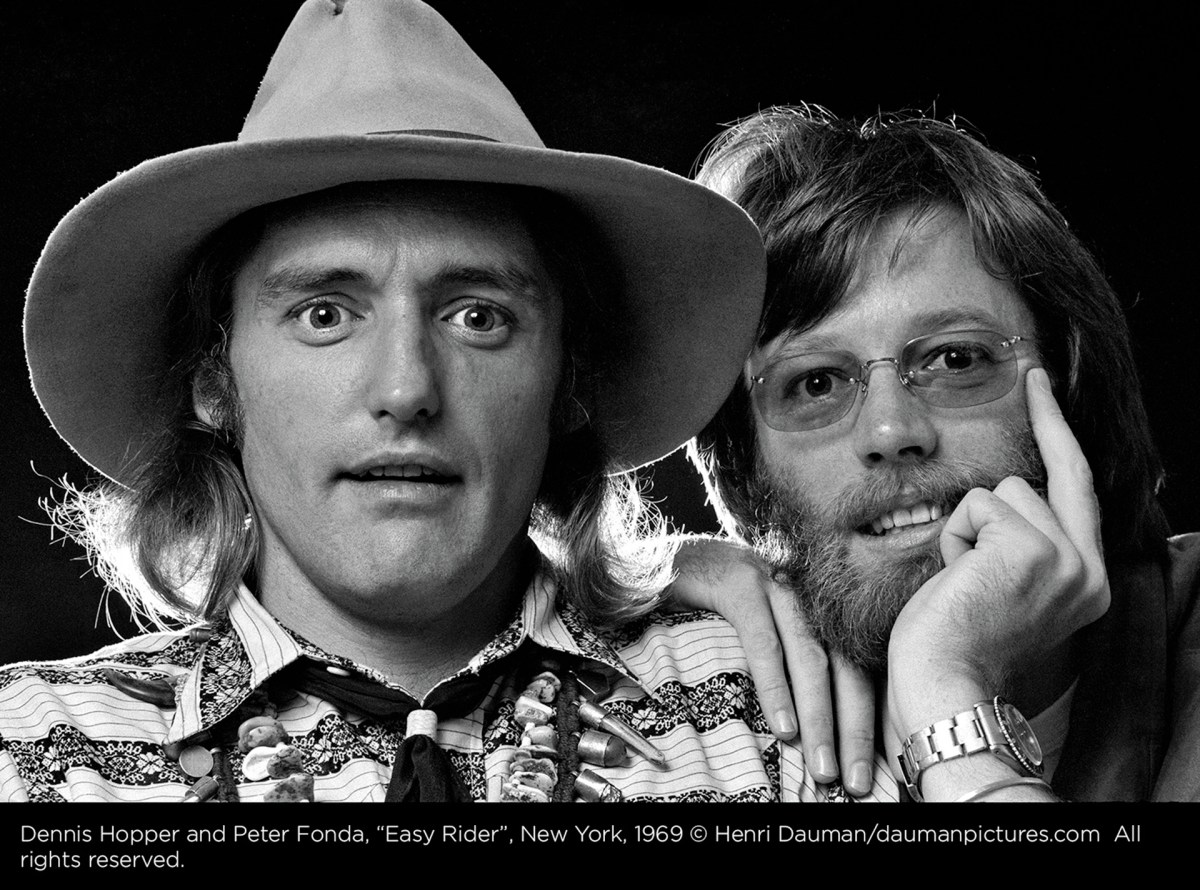

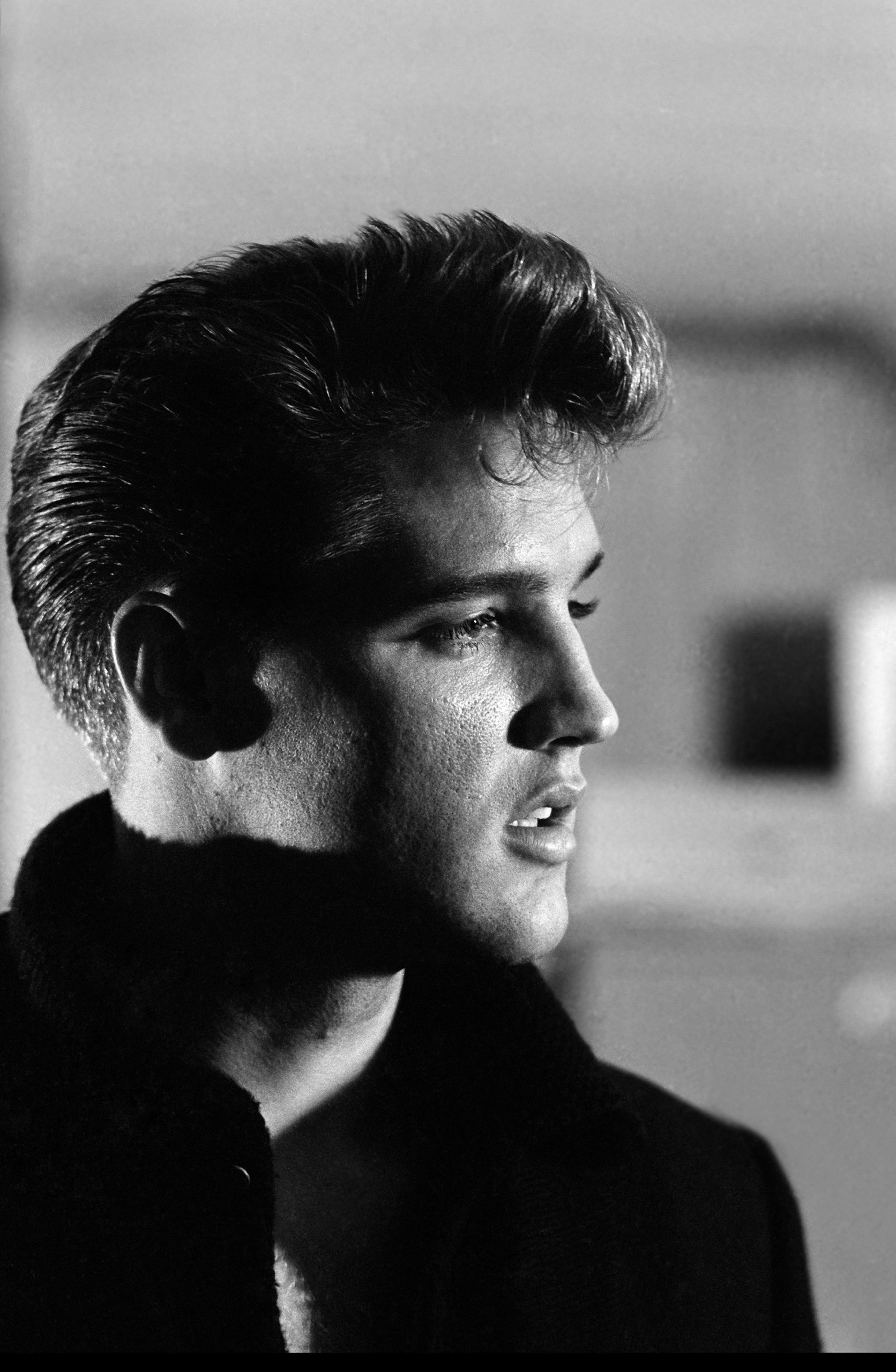

Henri Dauman, whose iconic images of President and Mrs. Kennedy, Elvis Presley, Louis Armstrong, John Coltrane, Andy Warhol, and hundreds of others graced the pages of LIFE magazine for decades, recalled his first camera with a smile.

“I bought it when I was still a child in France,” said Dauman, who lives in Hampton Bays with his wife, Odiana. “It was a twin-lens reflex Argoflex. I was shooting in the street, and I started to work with a couple of photographers — one was a fashion guy and the other was a photojournalist.”

If that sounds as if Dauman led a charmed childhood, he did not. He is a Holocaust survivor. His father died in the Auschwitz prison camp, his mother died after mistakenly taking rat poison, which was sold to her as medicine from the black market, and this was after she and her son had twice escaped being imprisoned themselves. The 13-year-old Dauman ended up in an orphanage at the end of World War II.

“I went to the cinema a lot. I was inspired by American movies,” he said. It’s a wonderful full circle that Nicole Suerez, Dauman’s granddaughter, started a ball rolling which eventually led to the documentary “Henri Dauman: Looking Up,” a film about Dauman’s life both behind and in front of the camera, which was screened at last fall’s Hamptons International Film Festival, and will be part of the Los Angeles Jewish Film Festival on May 5.

But back to the young Dauman, spending his days in Paris in a darkened theater, watching Hollywood films.

It was then that Uncle Sam beckoned. For real.

The 17-year-old got a letter from his Uncle Sam, who lived in New York City. “He asked me if I wanted to come and live in the United States, and I said, ‘Sure.’ I had been dreaming of New York, seeing it in movies and photographs. It’s such a photogenic city. It’s like a big movie set.” He came on a ship, “and what struck me first was looking at the dockworkers picking up the rope to tie up the boat, and there was snow and ice everywhere, and realizing that New York City was not quite like I imagined it,” he said with a laugh.

Bonding With His Subjects

There’s no way to describe how familiar Dauman’s images are to so many, although he remains practically anonymous. His photos encapsulated generations on film; not only celebrities but life in America in the 1950s, ’60s, and beyond.

But what was it like for a young, a really young, photographer to land a gig at LIFE Magazine at the apex of its popularity, the magazine which chronicled America, and be sent on assignments to capture some of the world’s most famous people? “That’s the thing, no matter how big their name is — whether it’s President Kennedy, Marilyn Monroe, Brigitte Bardot, anybody — they’re still human, they’re just like us. They just have talent,” he said.

Because of this attitude, he was able to bond with many of his subjects. “When I first started to photograph seriously in New York, some of them were just people I wanted to meet, and it became my university,” he said. “I learned more from them than from going to any school.” Movie stars, politicians, artists, scientists, mathematicians, Dauman chronicled them all. Two of his most famous images couldn’t be more opposite — a sweat-soaked Miles Davis blowing his horn, and Jackie Kennedy, poised and elegant beneath a black veil at JFK’s funeral after her husband’s assassination.

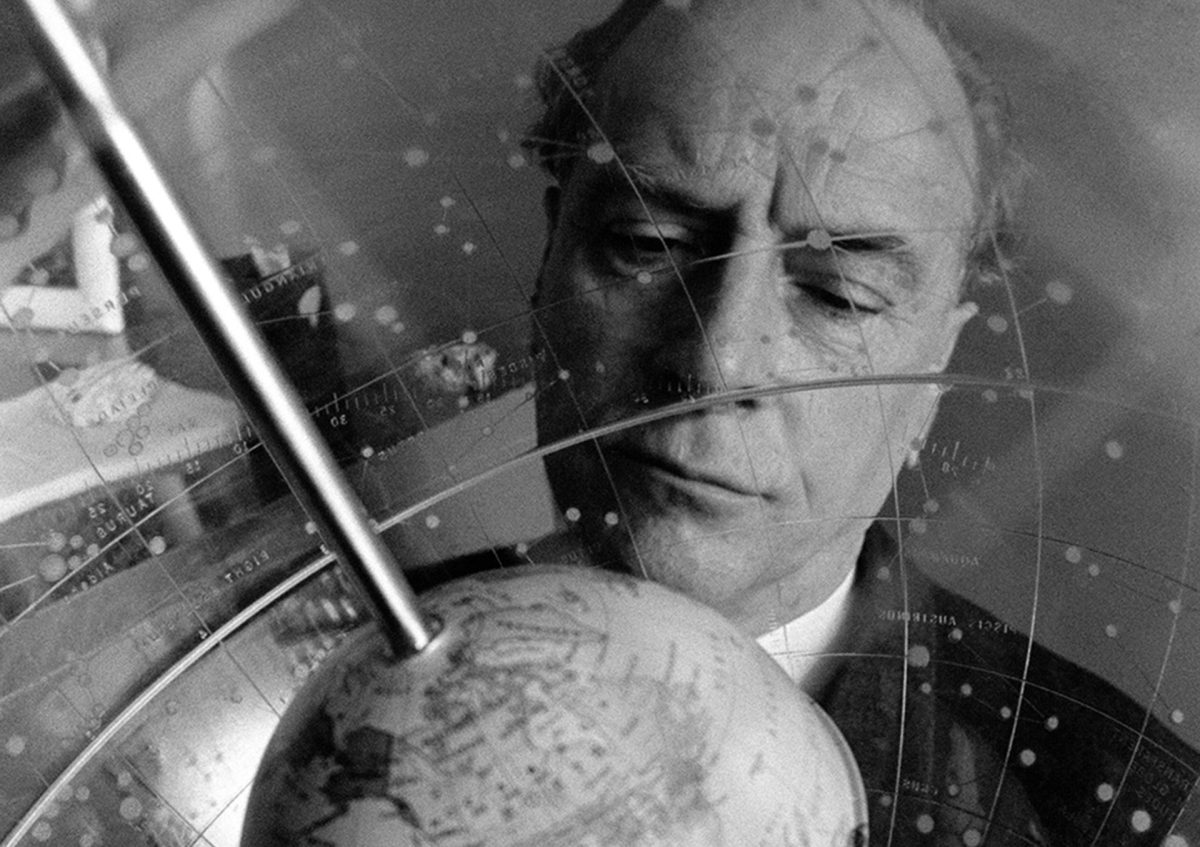

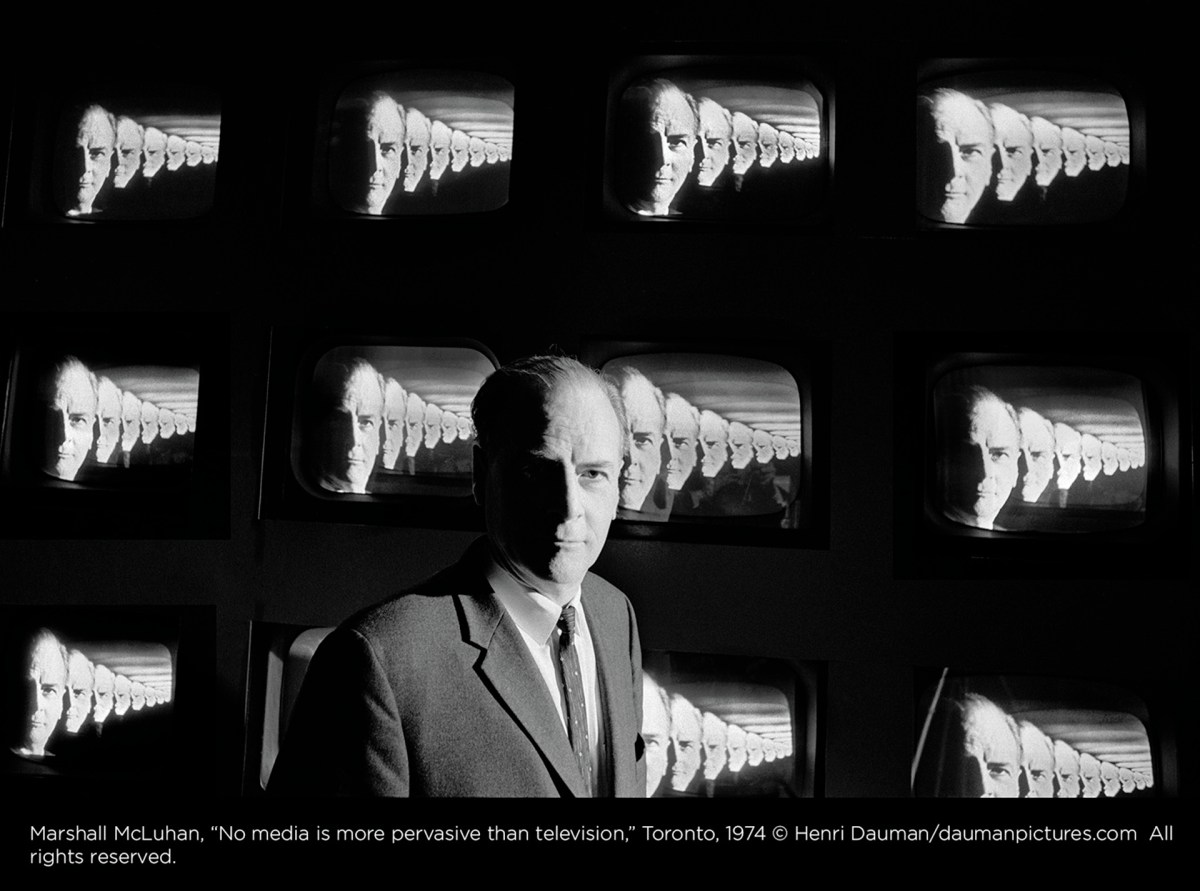

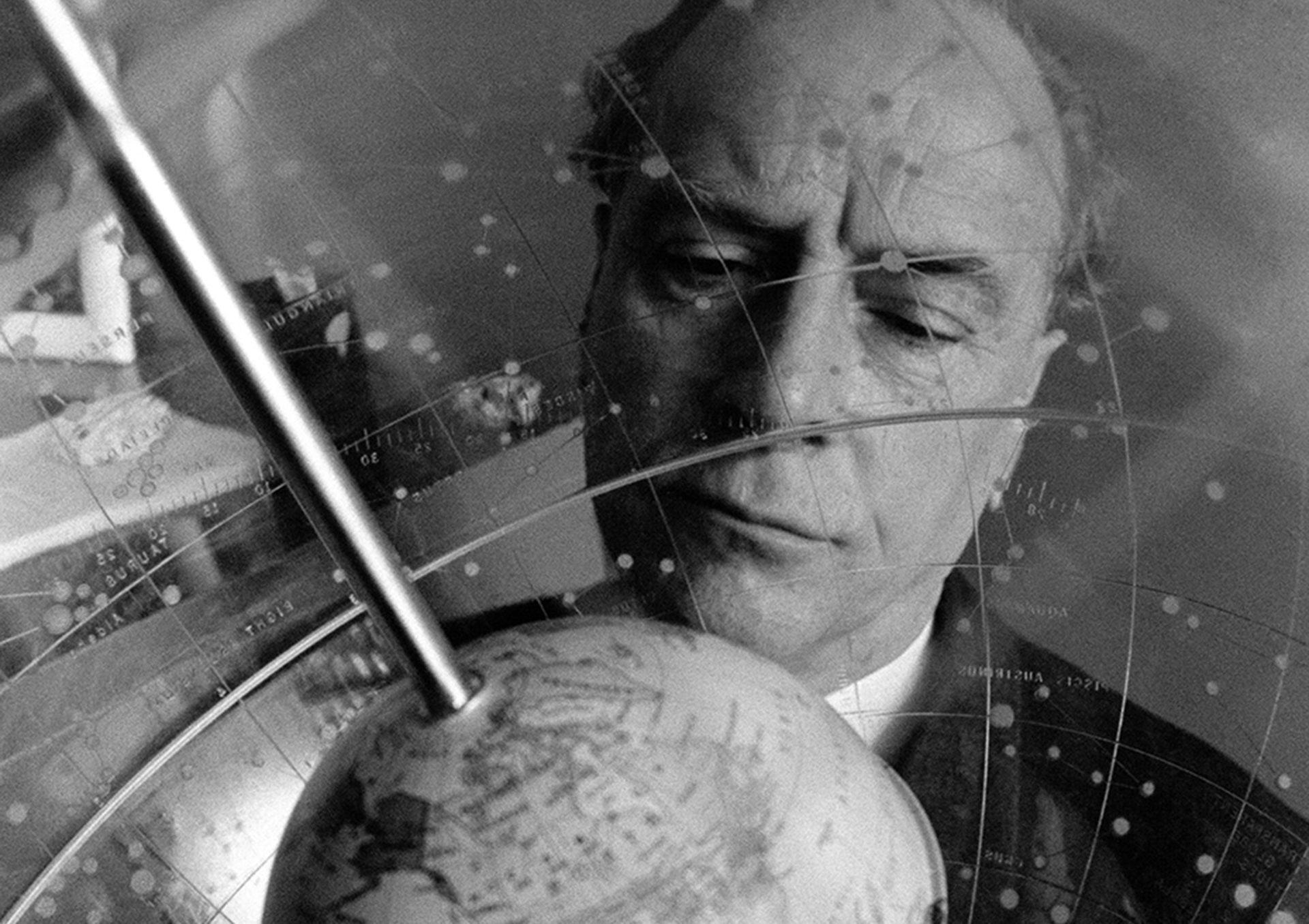

One of his favorite shoots was a surprise. “I went to Toronto to photograph a professor from the University of Toronto. He looked very much like you imagine a professor to be, like Jimmy Stewart,” Dauman said. “It was Marshall McLuhan,” philosopher at the front lines of media theory and the author of “The Medium is the Message.”

“I stayed with him for 10 days in Toronto. Nobody had ever heard of him. And he told me about all this stuff that was coming — portable phones, small computers, something like the internet. He predicted all of this. This was early 1970s. I didn’t know what he was talking about!” But the images that Dauman captured during his stay spoke volumes to LIFE’s eager readers and helped propel McLuhan and his supposedly zany theories into the spotlight.

Fondness For Film

“Some of the most interesting stories are the most complicated stories. Like who would have thought that to do some story on a hidden professor at the University of Toronto? And yet he had the answer to our future,” he noted.

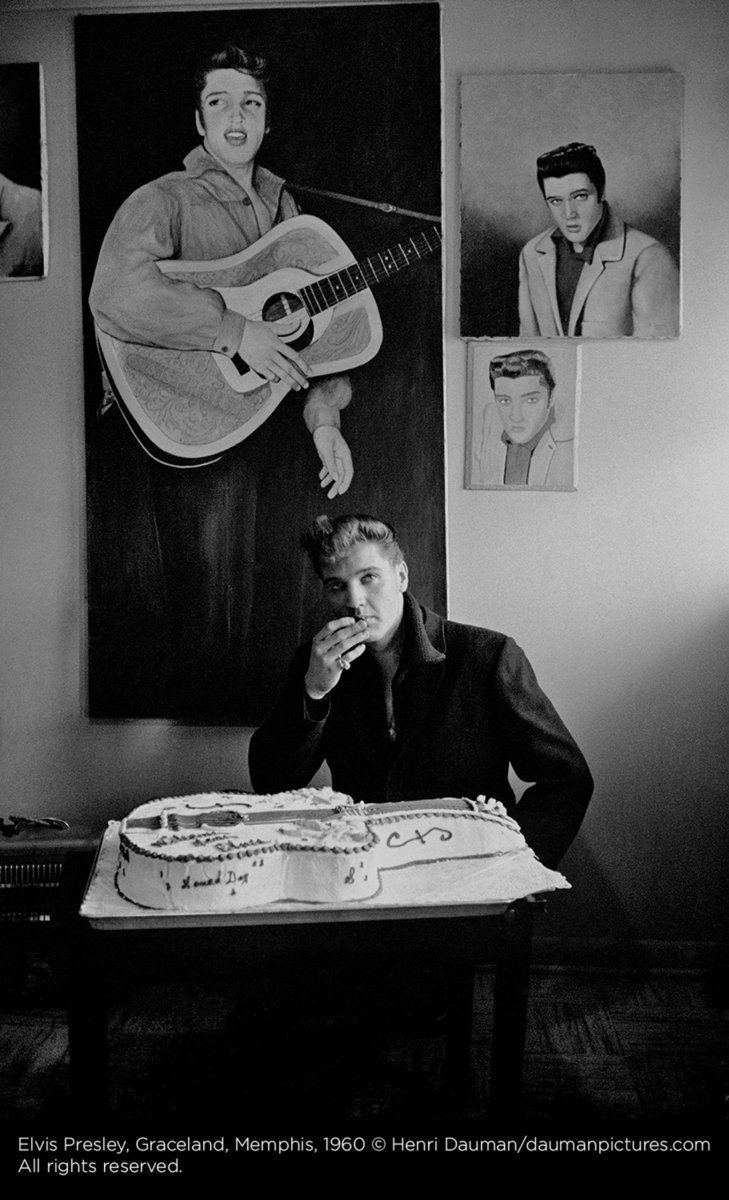

Dauman also spent time with Elvis Presley, straight after his return from the U.S. Army. The two bonded. “Somehow we were able to relate. He was surrounded by all these people, but we were able to sit together at his kitchen table and we would talk about the early loss of our mothers. He was so devoted to her. Losing her was devastating to him,” Dauman recalled.

Dauman returns to France May 8, to be present in Limay, where his mother hid with him during the war.

“It’s a small town maybe 40 kilometers from Paris. I’m going back there to show the movie, and also, they are putting a plaque at the war memorial there in remembrance of my father. Last fall, 500 high school children across France were picked to visit Auschwitz, including 18 children from Limay. Five of them wrote an essay about my father — four of the children are Muslim — and they made it into a play,” which Dauman will get to see.

As far as the lens being turned onto himself and his life, Dauman said, “I was reluctant to make the film, but it is these connections that make us human.”

As far as photojournalism today: “It’s not what it used to be. A very high percentage of young people get their news from Facebook and places like that. This work is not research. When we did a story for LIFE, or The New York Times, it was well-researched. It used to be, on assignment, the writer and the photographer completed each other, so it’s not writing about the photograph or shooting about the text, but both having the best interest of the story at heart.”

Many photographers bemoan the changeover to digital film, but Dauman simply shrugs it off.

“Digital film really came in while journalism was dying. And film still has a roundness which is unmatched,” he said. “Millions of people are taking pictures with an iPhone. A hundred years from now, what will survive? Will you be showing your grandchildren a wedding album on a computer? Film survives. It lasts. It’s what will still be here.”

To learn more, visit www.daumanpictures.com.

bridget@indyeastend.com