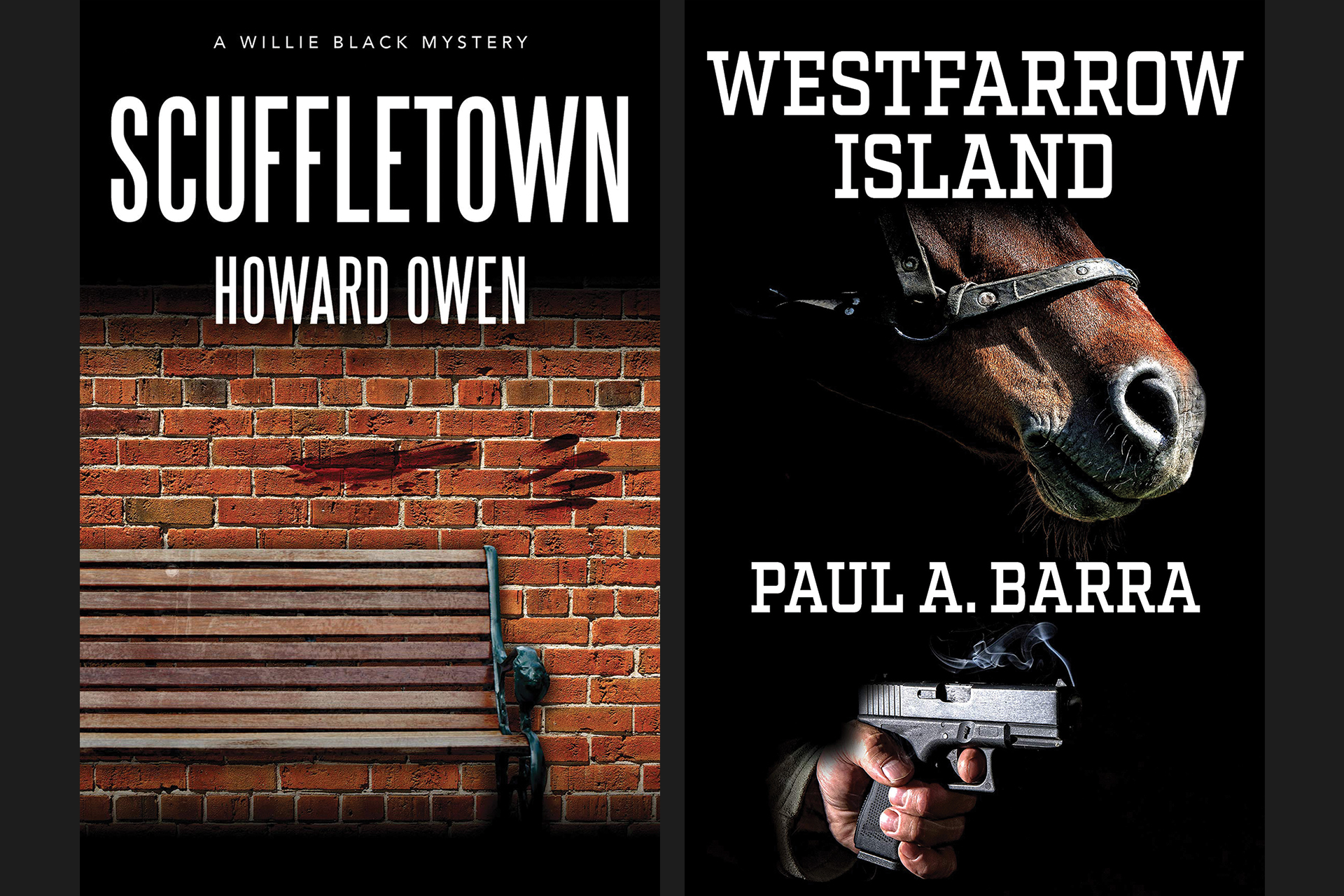

Two Crime Novels From The Permanent Press

In “Scuffletown,” Howard Owen’s new offering in his Willie Black murder mystery series, the intrepid, cynical, sardonic protagonist newspaper reporter from Richmond, VA is out to exonerate a good friend accused of murder. Willie, who’s part African American from Oregon Hill — “an alabaster ghetto of intolerance” — and a full pain in the butt to local cops and baddies, is 57 now, but he hasn’t lost it.

He’s on his fourth wife and has kind of adjusted to working the night beat on his “beleaguered” local newspaper, a job beneath him, of course, as the inexperienced young suit who owns the paper and Willie’s admiring colleagues well know, but it’s a job he does well, especially when he’s told not to involve himself in an investigation but does so anyway, upholding standards of journalism and justice.

Though the plot of “Scuffletown” seems a bit obvious, one of the book’s main attractions, as is usually true of a Howard Owen tale, is setting. The reader learns about a part of the country most people know little if anything about. Scuffletown is real, a part of the “Fan” district of Richmond (so named because of geographical design). As the book opens a crime has occurred in Scuffletown Park — lots of blood, though no one’s reported hearing gunshots. Odd, muses Willie: “Here in Richmond, we prefer to shoot each other. Knifing is just too damn personal.”

It turns out that Willie’s roommate Abe Custalow, part Indian, has been photographed at the crime scene. It also turns out that Abe refuses to discuss why he was there, clamming up to Willie, the cops and his money-mad black lawyer who, despite comical hustling, will do the right thing. All of which brings up the other element of fiction for which Owen is noted: the creation of a cast of engaging diverse characters.

In “Scuffletown,” many make return engagements from previous novels. These include Willie’s mother, Peggy, a self-medicating marijuana addict; Willie’s daughter Andy, Abe Custalow; Awesome Dude, a reclaimed homeless man who lives with Peggy; and a host of newsroom folks, local police, lawyers, and a former wife or two. Arguably, too many characters (and their stories) crowd onstage for a plot that extends only two weeks. Still “Scuffletown’s” a hoot, a fast and entertaining read and an affectionate elegiac tribute to print journalism.

Westfarrow Island

Paul A. Barra notes that the titular setting of his thriller “Westfarrow Island” off the coast of Maine is not real, but “could be,” as could be The Clemson Project, the black ops CIA-type machinations at the center of big guy Anthony Tagliabue’s adventures, which the reader learns about as the plot gets under way.

At first, though, the narrative focuses on a dead body that turns up on Anthony’s old work boat. Anthony appears to make a living as a fisherman, but he has another source of income which he reluctantly admits to his fiancée Agnes Ann. It involves commissions — assassinations and spy work — for a secret agency of the U.S. government.

Barra continually surprises the reader with new directions in his multi-layered tale, one of which involves the racing of Francine, a spirited two-year-old filly Agnes Ann managed to wheedle out of her nasty ex-husband, a lawyer for The Mob. Will he try for vengeance? How will and how well will Barra connect the racing subplot, Tony and Agnes Ann’s romance, the investigation into the murder of Anthony’s old fishing buddy and new assignments from his black-ops handler?

The author, a former naval officer and a newspaper reporter, writes of what he knows, which amounts to an impressive amount of lore about boats, fishing, navigation, the backwoods of Maine, as well as guns, horse grooming, and racing, especially in Saratoga Springs, and the Mafia.

An epigraph, two beautiful lines from a Robert Browning lyric, signal a writer who cares about language, and indeed Barra demonstrates that in an opening sentence rich in metaphor: “People who drifted in a certain stratum of Bath society knew the sailorman named Joshua White, a man whose face was gullied by salt air, coarsened and darkened by sun, and whose life was a solitary pursuit.”

Other literary touches evidence a writer who risks structural innovation — the tale is told mainly from an omniscient third-person point of view but occasional chapters in the first person by Agnes Ann soften the view of the big guy. If the resolution to the several narrative strands seems a falling off, evocation of place nicely compensates, and there is sufficient suspense to keep reading.