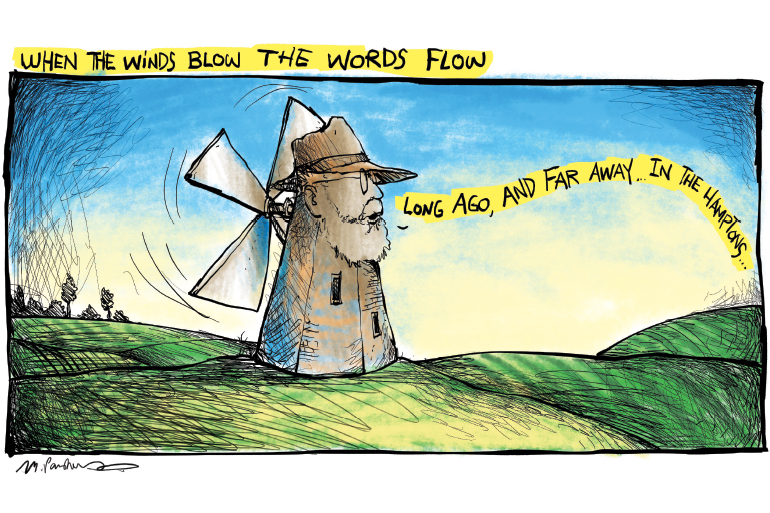

The Hamptons' 11 Historic Windmills Were Built from 1788–1820. Why?

The eastern end of Long Island is graced with 11 historic wooden windmills. This is the largest collection of such mills in the United States.

I have sometimes wondered why these tall windmills—their blades rise to 40 feet—were built here and apparently almost nowhere else in America. I have also wondered why nearly all of them were built during the 15-year period between 1795 and 1810. Was it some kind of fad? Was it some expert who came here, persuaded everybody to build a windmill and then left? Was it something else?

There is an answer as to why they were built here and almost nowhere else. Back then, people lived off the land. They grew fruits and vegetables that they traded or sold with nearby neighbors. They raised livestock. They harvested grain or wheat. They chopped down trees and built homes or stockpiled firewood. They fished or hunted. Whales were plentiful in the sea and their blubber could in theory be melted down and used to light rooms, thus replacing tallow. But in any case, trading at a distance was rare, though it could be done by boats or by oxen or horses pulling carts. There were no roads as we know them.

The power to turn wheels and grind corn or grain was accomplished by mills. Most were water mills, which sat alongside rivers that pushed the water along. But eastern Long Island had no rivers. The land was nearly flat. And though a water mill was created on a bit of rushing water between two ponds in that area, the rest of the settlers turned to wind power. It is believed there were windmills built on the East End before 1795. There are historic references to them. One is mentioned as having been built in Southold on the North Fork in 1644. But they were called Pole Mills, because they were just the blades and gears on poles without the cedar-shingle enclosures. None survived the difficult East End weather for long.

So what happened beginning in 1795? Well, new windmills were built with their gears enclosed inside six-sided tapering wood-shingled walls in the shape of farmer’s “smocks.” They became known as Smock Windmills. The year 1795 also coincided with the end of the American Revolution, and people, for whatever it was worth, began to think more about using new technologies, particularly European technologies. Windmills, with their sails, shafts, gears and two spinning stone platters inside, suddenly took hold, used for grinding by manipulating the stones with levers so corn or grain could be crushed between the stones.

It was also discovered by a local clock maker named Nathanial Dominy that the windmill cap could be turned so the blades could face the changing location of arriving wind not just by using a long “tail pole” with a wheel at the end—which could move along the ground as people pushed it, dragging the cap way up at the top along—but by the operation of new gears inside.

Interestingly, even with their “smocks,” eastern Long Island windmills were never considered buildings. They were considered farm equipment, and they could be bought and sold and moved from place to place. Many windmills have histories of having been in four or five different places before they came to where they are today. The timbers that run along the base of the windmills rest merely on large boulders, not on foundations. The mills could be easily moved around.

Why was the production of local windmills suddenly stopped in 1820? Without a doubt, it was due to the creation of steam power. The first commercial steamboat in America carried freight between New York City and Albany in 1807. The ship, designed by Robert Fulton, was called the Clermont, and the 150-mile trip took 32 hours. After that, attempts were made to use steam engines—coal or wood burned in a furnace to heat a giant container of water above whose steam could turn a gear—to power farm equipment. By 1820, it’s been estimated there were nearly two dozen windmills on the East End, enough for any village to have at least one and probably two—with the notion in the air that these were soon going to become obsolete when these experimental steam engines could be arranged to replace the wind as a power source.

So nobody built more than what they had.

The first steam-powered mill was built in Bridgehampton in 1850. The handwriting was on the wall. And when the first steam-powered locomotive hauled its train on tracks from New York City in 1872, it was possible now to order sacks of flour and grain from a factory up-island and have it on the East End later that same day. Thus ended the age of the beautiful old windmills.

Interestingly enough, these old windmills mostly fell into disrepair during the next 90 years. Saving history was not a priority. Progress was a priority. In Bridgehampton, the historic Wick’s Tavern, used by soldiers during the Revolutionary War, was torn down in 1941 and the lumber taken away for use elsewhere. In Manhattan, the magnificent Pennsylvania Station, a rival in size and glory to Grand Central Station, was torn down in 1963. Nobody cared.

There was even a plan by the Coast Guard in 1966 to abandon and eventually use wrecking balls to tear down the Montauk Lighthouse. They’d replace it with a flashing light on a 300-foot-tall steel tower farther inland, because while the erosion of the cliff adjacent was getting worse and worse, it was determined the lighthouse could not be moved. This newspaper led a protest in 1967 to have that not happen. Some 2,500 people showed up just after sunset in the parking lot at the Montauk Lighthouse to demonstrate their disapproval of this plan. They carried torches, flashlights, flaming batons, lanterns and all matter of other lights so the Coastguardsmen could look out at it from the lighthouse upper floors not far away. The Coast Guard abandoned that order.

Here’s a list of the Eastern Long Island Smock Windmills. Many have been lovingly restored to how they were when first built. Others remain in disrepair, and at least one, the Shinnecock Mill, on the campus of Stony Brook Southampton, had its insides cleaned out to become a “cottage” for visiting professors to stay in. In 1957, that visitor was playwright Tennessee Williams, who, while there, wrote The Day on Which a Man Dies about his friend, painter Jackson Pollock, who was killed in a car crash the year before. The mill is also thought to be haunted. In the 1890s, the daughter of the owner of the mill at that time, a girl named Beatrice Clafin, fell down a flight of stairs inside, broke her neck and died. People say they sometimes see Beatrice looking out a high-up window from inside the mill.

Beebe Mill, built in Sag Harbor in 1820, was one of the first windmills to have cast-iron gears. It was moved to Ocean Road and Hildreth Avenue in Bridgehampton in 1837. It remained in operation until 1915, and on its site was lovingly restored to its original state by restoration expert Robert Hefner, who did the job using tools available at the time it was created. Beebe Mill is perhaps the prettiest of the windmills, with decorative designs on its exterior.

Gardiners Island Mill, built on that island in 1795, is the only East End mill whose shingles are painted white. It also sports a weathercock in the shape of a rooster on its cap.

Hook Mill was originally built where it sits today, on the green just east of the center of town of East Hampton, in 1806. It was another mill meticulously restored by Hefner and it is open for brief visits in the summertime.

Mulford Farm Mill was built in 1804 on Hunting Miller’s farm in the Pantigo section of East Hampton. Moved in 1850 to Egypt’s Lane, it was moved once again in 1917 to Mulford Farm across from Town Pond in East Hampton.

The Corwith Mill was built at Hogs Neck Noyac in 1799, and moved to the town green in Water Mill in 1814. It replaced an earlier mill that was destroyed in a blizzard in 1811.

Wainscott Windmill was built in 1813 in Southampton and moved to where it stands today, next to a tennis court in the private enclave known as the Georgica Association in Wainscott.

Sylvester’s Mill was built in Southold in 1810 and moved to the Sylvester Manor plantation on Shelter Island in 1839.

Shinnecock Hills Mill was built in 1712 on Windmill Lane in Southampton and moved to Mill Hill Lane in Shinnecock, and then to another Shinnecock location where it sits today. The first move was in 1890, the second in 1916.

The Hayground Windmill was built on a farm in Hayground and then, in the 1950s, sold to a private homeowner who placed it on his property just off Further Lane in East Hampton. Its private road is called Windmill Lane.

Gardiner’s Mill was built in 1804 at 38 James Lane in East Hampton and remains there today, open to the public, just across from Town Pond in East Hampton.