Danny Peary Talks to 'Mystify: Michael Hutchence' Filmmaker Richard Lowenstein

In the last few years, a number of documentaries have been made about iconic rock singers and groups. One of the best played at the recent Tribeca Film Festival. Writer-director Richard Lowenstein’s standout Mystify: Michael Hutchence tells the compelling story of the charismatic and wildly-popular lead singer of the Australian supergroup INXS from 1977 until his death in 1997.

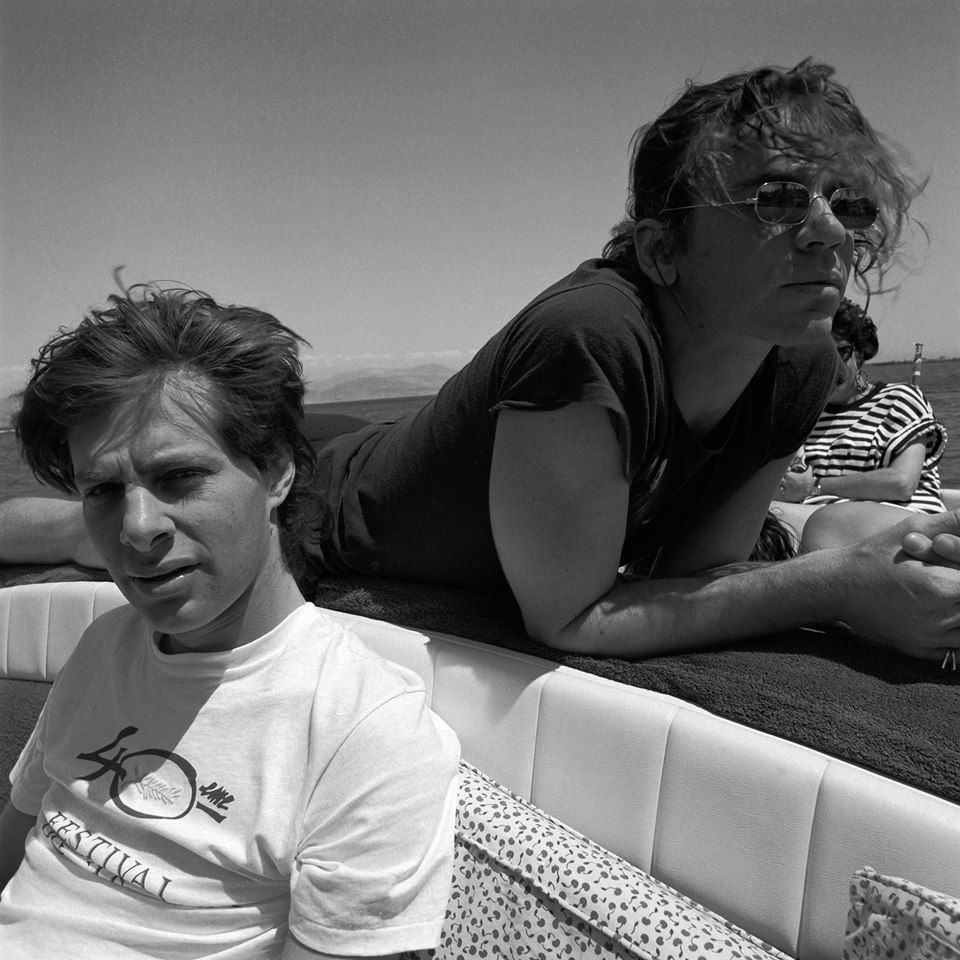

Lowenstein, also an Australian, had two significant things going for him: He and the charismatic Hutchence were longtime friends and he directed him in videos and the quirky film Dogs in Space; and he knew or had access to many pivotal people who tell Hutchence’s life story in the movie, including his celebrity girlfriends who made scandal-sheet headlines with him: Kylie Minogue and Helena Christensen. And there is great footage of him performing, some never seen before.

I admit to having known little about Michael Hutchence other than his name and his shocking suicide in Sydney, but now that I know what a remarkable talent he was and what an interesting life he led, I hope to learn and listen even more.

Watch the teaser (or see Teaser 1, Teaser 3)

I enjoyed having the following conversation with Richard Lowenstein during the festival.

Danny Peary: You knew Michael Hutchence well, as his friend and the director of INXS videos and Dogs in Space, in which he played the leader of fictional band. My guess is that you wanted to make Mystify to show he’s not the typical rock star but the person you knew.

Richard Lowenstein: That was one of the many reasons. But initially I was fascinated by and couldn’t believe the Greek tragedy nature of his story, complete with Zeus throwing down a bolt of lightning in the middle of it. With songs too, with a Greek chorus. I was very disturbed by his passing, as were a lot of the people who talk in the film, and it took a long time for all the chaff to stop flying around us—all the different rock-star theories, like, “He must’ve been like the guy on Entourage” or “He must’ve been like Jim Morrison,” because he looked a bit like him. There were a lot of people just filling in the gaps with those clichés, and everything I’d see, whether it was a documentary or drama, would make me say, “I don’t recognize that person. It looks like Michael, but he’s nothing like what I experienced.”

I have worked with a few rock stars, including Pete Townsend, Bono, and David Bowie, and they’d all create personas so they could hide their real selves from the public. Michael didn’t have a persona, In the film he talks about putting on a persona when things got too big. But he was just him. He went out on stage to perform in front of audiences he couldn’t see in the dark and, as if he were under some magic spell, would, like that saying, “dance like no one is watching.” I wanted to make a documentary of this fascinating story of a rock star who wasn’t really a rock star.

DP: The first time we see Michael Hutchence in the movie, he comes on like the magician/performance artist Cris Angel, even looking like him a bit. Did you title the movie Mystify because he had a mystifying aura?

RL: Well, Mystify is the title of one of his best known songs so it made sense to title the movie that, but also it was a very mystifying experience just making the film. We started making it nine years ago, and at the time I thought I knew him very well. I’d met him, I was his friend, I directed his videos and a movie, but when I looked back into my time with him I realized I had no idea who he really was. I started asking, “Who the hell was he?” I hadn’t found his Rosebud yet. And then we started putting together the jigsaw puzzle and saying, ‘Here’s a missing piece, and here’s another missing piece,” and when all the missing pieces were found and put together, I said, “Now I actually feel I know him.”

DP: Me, too.

RL: Thank you.

DP: You spent a lot of time with him, but I wonder if you were reluctant to put too much of yourself into the movie so found people who would say exactly what you would say. Is that accurate?

RL: That’s accurate, but it wasn’t a conscious decision, I had Lynn-Maree Milburn, my co-producer and co-editor, interview me for five hours. However, I found I didn’t add much more to the picture as a narrator than I could add as a filmmaker, I couldn’t say, “What I said was really good next to what Bono said.” I felt I could say everything I wanted to say about Michael by making the film, by showing what I think fleshed out the story above what the public already knows. I even designed the film to be about an unknown rock star, because there is no guarantee that everyone who sees it will know anything about Michael and INXS. I structured the film for “the person who thinks they know nothing.” Then in watching the film, that person might go, “Oh, Michael Hutchence is that guy” or “I have heard that song, I just didn’t know it was by INXS.”

DP: Well, thank you for doing that. I’ve heard the hit songs and knew the names Michael Hutchence and INXS, but I didn’t make the connection. I know The Beatles era!

RL: Me, too. I’m from Melbourne. which is not a very INXS city; it’s more Nick Cave.

DP: You mentioned Greek tragedy, so if you look at his life, was he fated to have such a tragic ending, with his head injury and suicide from hanging?

RL: I thought a lot about this. There’s the Greek tragedy of Icarus flying too close to the sun and being burned. But I thought Michael actually didn’t do that. He wasn’t a star who took too many drugs like River Pheonix or drove his car too fast like James Dean. He actually had gotten past that stage and was doing his job and being a nice guy, and then a bolt of lightning hits him. He’s eating a slice of pizza while bicycling in Copenhagen with Helena Christensen and I think he banged on a taxi cab—”get out of the way”—and the driver comes and thumps him, and he falls and hits his head on the curb. I don’t think it was fate, it was just something that came out of the blue. A deus ex machina, as in Greek tragedy.

If you were writing this, you couldn’t write anything that is more perfectly structured. He was knocked off his perch and it was weird that not only was there brain damage, but there was the loss of his taste and smell, which took away the things he loved the most. As his rewards from being famous and adored, Michael wanted respect but also the pleasures that came with it.

DP: He was a hedonist.

RL: And hedonists use their senses of smell and taste.

DP: The irony was he was obsessed with Patrick Süskind’s bestselling book, Perfume.

RL: Which he’d told me about long before his accident, on the set of Dogs in Space, which we made in 1986. He told me, “You’ve got to read this book!” I thought it was a bit misogynist, but he’s going, “It is fantastic!” You saw him with his female partners and how they enjoyed good wine and good food, and then suddenly he has this accident that will prevent him from enjoying either. What, are you kidding? Michael had been a very calm, easy-going, friendly person but suddenly he had all this anxiety and he’s locking horns with people.

DP: I see him in your movie as the nicest guy in the world before his accident, although he was flawed in certain ways. After the accident he became like Jekyll and Hyde, but long before that he related to The Picture of Dorian Gray. He believed his handsome outer self was hiding the bad side that didn’t emerge until after he had brain damage.

RL: Yeah, I think Mike always concealed his secret desires, or his naughty side. Michael did have a fascination with the raunchy side of life. That’s why he loved Kylie Minogue. On the surface, they were portrayed a certain way, but behind closed doors they liked getting into mischief. It was like there was an even balance between their public and secret sides. That said, that was totally different from what was rumored about him following his death, especially about autoeroticism. None of his girlfriends that I spoke to mentioned anything that went to that level. Even Erin, the who was there at the very end, said that wasn’t part of his sexual pleasures.

DP: So some people thought his hanging was a sexual act gone wrong?

RL: Yeah, there was rumors all over the British tabloid press about that. In regard to seeing his own flaws and comparing himself to Dorian Gray, Michael wanted the respect of his friend Nick Cave, but he took the easy route. It’s like he made a Faustian bargain. The easy route was: “I’m a very attractive man singing Need You Tonight.” He wanted the respect and artistic credibility of Nick Cave, but did he actually get off his bum and chase that? I don’t think so. Because he needed someone—as when he recorded his solo album—to grab him and say, “Come and do this with me.”

He wasn’t a motivator like Bono or Pete Townsend; he wasn’t someone who’d say “I have a great idea and you’re all going to follow my lead.” Instead, he let things happen to him. He was quite a passive character. And sometimes that lead him into this world where he was being pulled in different directions. For instance, the members of INXS were telling him, “Let’s make another hit,” while his accountant was saying “Let’s do this,” and his business partners were saying, “Let’s do that.”

DP: He wanted to be recognized as an artist.

RL: But the lure of lightweight success and popularity, especially at the time of the Kick album in 1987, was very attractive. And it was easy for him to be caught in this schism where he’d go, “It would be great to have another hit, but I also want the same music respectability as my sources,” his sources being Aretha Franklin and…

DP: …all the great, eclectic singers he heard growing up. So much of who he was, the film shows, dated back to his youth. That he repeatedly sabotaged his relationships with terrific women who were good for him and he loved was indicative of his refusal to allow himself happiness. And I think that refusal can be traced to the guilt he still felt for becoming rich and famous while his younger brother Rhett got the shorter straw in the family. Their mother even took her older son to be with her in America, and left poor Rhett behind with some woman.

RL: As we see in the film, his guilt was evident when he asked, “Why is this success happening to me? And why is it happening so easily for me?” Michael worked hard, especially with the mechanics of playing, but it was as if he got touched with the golden wand, and the hit songs just appeared to him and his co-writer Andrew Farris. They came in only five minutes. And then he had a brother who’d always found everything difficult. That goes right back to their parents who adulated Michael and kept criticizing Rhett. It was like the golden boy and the black sheep. And Michael felt guilty. Just as he felt guilty when he had to break up with someone. It was a similar guilt.

DP: But he always broke up instead of trying to work things out, and it was probably never for his benefit.

RL: He didn’t break up for his own benefit but because he was following that Faustian bargain. He was going after some goal; something was driving him to go on to the next thing. And though Michèle Bennett, or even Kylie Minogue, probably would have been the best thing for him, he always wanted more.

DP: You say more, but with Michèle, his first true love, he says, “She’s too good for me.”

RL: Yes, but I think there’s a double side to that. What he means is: “She’s too good for me, because I want to go off and be naughty.” He was just like a kid in the candy store. Michael may not have been the most monogamous of people, or rock stars, but he didn’t enjoy breaking that monogamy bargain, especially later in life. He wasn’t proud of, “Oh I just slept with someone on the road while my girlfriend doesn’t know about it.” He would have guilt and ring her up and confess, “I’m so sorry, I did that,” although he had the opportunity to hide it all. I think at that point in time, when he broke up with Michèle, he was thinking, “The world is my oyster.”

DP: He was very young then, too young to settle down.

RL: Yeah, 26. Michèle was beautiful and intelligent, but was almost like this keeper, as you hear in the film. But some rock stars—his friend Bono, for example—meet their partners in high school and stay with them the entire time. For them, family is like a rock that keeps things in balance. Michael kind of wanted that, but—getting back to his faults, his fallibilities and even the Dorian Gray thing—he didn’t want to do the hard work to get it. Rather than committing to family life and having home as his base, he wanted to be this nomad.

But then suddenly he said, “I’d like a family,” so he became involved with British TV host, Paula Yates, and had an instant family, which was her family with her husband Bob Gedolf. He suddenly had three daughters of another person and family. And he and Paula also had a baby he adored, Tiger Lily. But he was coming a bit unstuck because of his accident.

DP: Did you ever talk to him about women? Did you give him advice?

RL: I think he gave me advice. He was very interested in what I had to say, but back then I was having romantic issues as well and he would give me advice about them. Some people with messed-up love lives like to tell others what to do.

DP: Did he ever consider being with a female who wasn’t beautiful? Would he have gone with women of intellect?

RL: Oh, absolutely. Michael’s public image was of a rock star who was always with women who were totally gorgeous. But there were many women that he was with in private along the way, and it wasn’t always about looks. And it wasn’t, “Whoa, I’ve met you, and can we go to bed as soon as possible?” He would sit there talking art and politics with them till four or five in the morning.

DP: What did he like to talk about with you?

RL: He was very home taught, let’s say. Most of these rock stars leave school at 15 to go on the road; and there are ones that stay in that infantile state and there are others like Michael who actually start reading and saying, “Since I’m not going to university, I’ve got to teach myself.” He read voraciously, probably more than me and I did the whole college thing and film school. He tried to educate himself, he read as much as he could, even the Marquis de Sade, and would sit there and talk in a homespun way about art and politics, even though sometimes he wasn’t all that informed.

DP: In your film, he is shown to be naïve when guesting on a TV show and pretending to be sophisticated.

RL: He tried to speak with a French accent, although it’s an Australian problem that we can’t pronounce French very well. He would sit there and if you knew more than him about a certain issue, he would listen closely and then pass on what he learned to the next person as if he was an expert on, say, aboriginal land rights. You’d say, “Michael you need to meet this guy, Gary Foley, an aboriginal lands right activist,” and they’d go off and hang out for a week or so, and then he’d travel to America and start spouting all this stuff that he’d just learned from Gary Foley. He was like a sponge. He wanted to talk about these big issues, but because of the life on the road he had limited faculty to take it all in.

DP: He was friends with his INXS members, the Farris brothers, but did they ever go to museums or art shows with him or talk about books or politics with him?

RL: I don’t think they were that type, no. I think Michael did love them all and he connected to them as brothers. However, like with a lot of families, there was a little bit of dysfunction. He liked different things than they liked. He liked to challenge the status quo of the music at the time, getting into alternative music. He also got into alternative literature. As a result, sometimes he felt very much alone because he was stuck in a bus during rock and roll tours with band members who did not share his interests.

I ended up telling Michael’s story through his girlfriends and those he was most intimate with. They were the people who saw him at his most vulnerable and he felt safe with and connected to both intellectually and emotionally. They’d read similar books and they would travel together, laugh together and go to art galleries and museums together, and have discussions about it. On a tour bus, it would often be just a bunch of men joking around.

DP: How Australian was he?

RL: He was Australian in the way a lot of Australian men are. We don’t like to talk about our feelings or emotional problems. When we do, it’s all brashness and bluster. We can talk about a book or movie, art, politics, all that sort of stuff, but sometimes we have trouble just talking. But to a girlfriend, we open up.

DP: It seems that he had a female sensibility.

RL: Absolutely. Without being effeminate, he had a female connection, and it is not surprising that the majority of his best friends were women. He had a very large number of female friends, like his personal manager Martha Troup, who speaks a lot in the film, and Lian Lunson, who I interviewed for a great length of time about Michael.

DP: As you know, our mutual friend Lian Lunson was an actress in Australia—she was in Dogs in Space—who moved to L.A. and became a prize-winning filmmaker. Were Michael and Lian a couple?

RL: No, he didn’t have a romantic relationship with her. Lian was Michèle’s best friend. She knew Michael extremely well, around the same time as Michèle, they all hung out at a shared house in Sydney for a while and were thick as thieves. Even after he broke up with Michèle, Lian and Michael stayed in touch. Of course, Michael called Michèle the day that he died.”

DP: So was Michael Hutchence a real person or a fake person?

RL: I do believe that by the end, or even earlier, Michael wasn’t quite sure who he was himself. He was very confused about who he wanted to be. Did he want to be a Bohemian artist? But he was very real, and that’s why I made the film. He was larger-than-life so people look at him and go, “He’s a celebrity, he’s a fake, it’s all artifice,” but he was a very real person who just did things differently.

Everyone asked, “Was he going to marry Paula Yates? Was he going to marry Helena Christensen?” I think he might’ve mentioned it, but did he really want to? I don’t think so. He was afraid of becoming a settled family person. He had a bit of a Peter Pan complex. Like a lot of us, he was very scared of getting old.

DP: Finally, how did he touch you most?

RL: Just by being a very simple, humble man, and just looking you in the eye and being genuinely interested in who you are. There are not many celebrities who are really interested in who you are. Michael was an exception.

Danny Peary has published 25 books on film and sports, including Cult Movies,Jackie Robinson in Quotes, and his newest publication with Hana Ali, Ali on Ali: Why He Said What He Said When He Said It, about the origins of her father’s most famous quotes (Workman Publishing).