Rosenblatt: Professor and Author Offers One-Man Show at Bay Street

A little after 8 p.m., the crowd at the Bay Street Theater began to settle down. Onstage was a piano, a piano bench and a table, upon which sat several dozen old, worn hardcover books, with a few extra ones spilled out onto the floor. And two chairs.

We were all waiting for the man from Quogue who had announced this would be a first, his first one-man show. Everybody knows this man, or if they don’t they were brought there by someone who does. I think many people, particularly those who have known him for years, were thinking, What took you so long?

There is a very short list of people, particularly literary people, who can get up in front of a crowd and, for two hours, spellbind them. In recent years Spalding Gray and David Sedaris have done it. Before that we had Will Rogers and Jean Shepherd.

After a few minutes, Roger Rosenblatt ambled out. He’s almost 80, pleasant looking, wearing a black sweater and pants and looking very much like the college English professor and award-winning essayist and novelist that he is. His topic, as the media and invitations said, would be about words. There was light applause.

“You’re probably wondering how the title of this one-man show came about,” he said.

We all looked at our programs. The title reads LIVES IN THE BASEMENT. DOES NOTHING.

“When my granddaughter Jessica was in the third grade,” he said, “she invited me to her school so she could introduce a writer to her class. I stood up. She said ‘This is my grandfather, Boppo. He lives in the basement and does nothing.’”

And that’s how this began.

Rosenblatt walked over to the table and picked up a book. “Ralph Ellison,” he said. “The greatest American novelist.”

He picked up another.

“Victor Hugo. He wrote with no clothes on.”

Another book.

“Agatha Christie. She took baths in fruit.”

Another book.

“This is Mary Shelley. Four-on-the-floor amazing. At age 18, she created the greatest myth since the Greeks. Frankenstein. He told the scientist who made him he wanted to be human. He was told no. This is the true sin. He can’t be a human. This turns him into a horrible creature. Of all the writers I’d most like to meet, it would be Mary Shelley.”

He stopped and looked at the audience.

“Balzac drank 50 cups of coffee before he sat down to write,” Rosenblatt said.

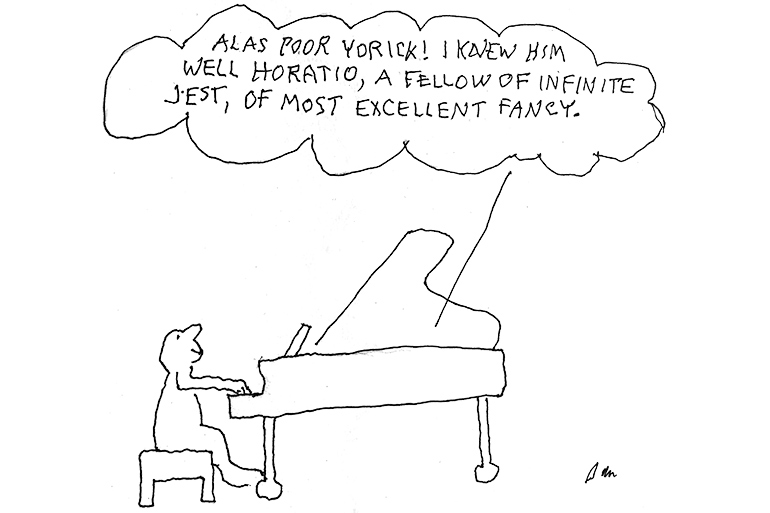

Rosenblatt then sat down at the piano and played a show tune from the 1940s. He’s okay at it. Not great. He stopped.

“I do this every morning before I write,” he said. He played some more, then stopped. “I am searching for the next note. I find it. Now I can hunt for the next word.” He riffed on a chord. “There’s a relationship between music and writing. One leads to the other, both ways.”

He stood up and walked across the room.

“Two Irishman are walking along. One of them is carrying a sack. The other one says, ‘If I can guess the number of chickens in that sack, can I have one?’ The other says. ‘You do that, you can have both.’”

Another book.

“Darwin. The most imaginative writer. He sees what wasn’t there.”

Rosenblatt now has a nice rhythm going, and for the next 90 minutes he tells stories, makes jokes and plays the piano while going back and forth, with the audience hooting and laughing along.

He talks a while about the word “said.”

“Writing teachers will tell you, don’t use the word ‘said’ too much, But there is no other word quite like it. Try writing ‘Look out for that falling rock, he articulated.’ There are a lot of ‘saids.’ You have to get them all out.

“I wanted to find out who wrote the song ‘Time Goes By.’” He continued. “Turns out it was a man named Herman Hupfeld. I looked to see what other songs he wrote. He only wrote one other. ‘A Hutch in Hoboken.’ That was it. Herman was a man for the H’s.”

Then it was back to another book. An hour and a half later he asked author Alice McDermott in the front row to come up on stage. He arranged the two chairs, and they sat and discussed the ins and outs of book tours, which included the dreaded Q and A’s that invariably follow.

McDermott, at a Philadelphia bookstore, was introduced by the store owner, who, reading from index cards, told the audience about the author and the earlier books she had written and how she had come to America from Nigeria, where she was born and raised. (which she was not.)

“That was not correct,” McDermott said. “What should I do? I decided to ignore it. After the reading, we had the Q and A and people asked intelligent questions about my work, and then a man raised his hand and asked, ‘How did your early life affect your work?’”

Laughter followed.

Rosenblatt said that at one Q and A an older man raised his hand and asked, ‘Are you related to the great Lithuanian Rabbi Ismael Rosenblatt?’ I told him no and went on to other questions, but then he raised his hand again. “‘You don’t look anything like him,’ he said.”

McDermott and Rosenblatt stood up and raised their hands. It was over. There was a standing ovation. A young woman came out, Rosenblatt’s granddaughter Jessica, now 18 and going off to college, and the crowd applauded her. Flowers were brought out for Jessica and McDermott. And that was it.

An evening with Roger Rosenblatt.