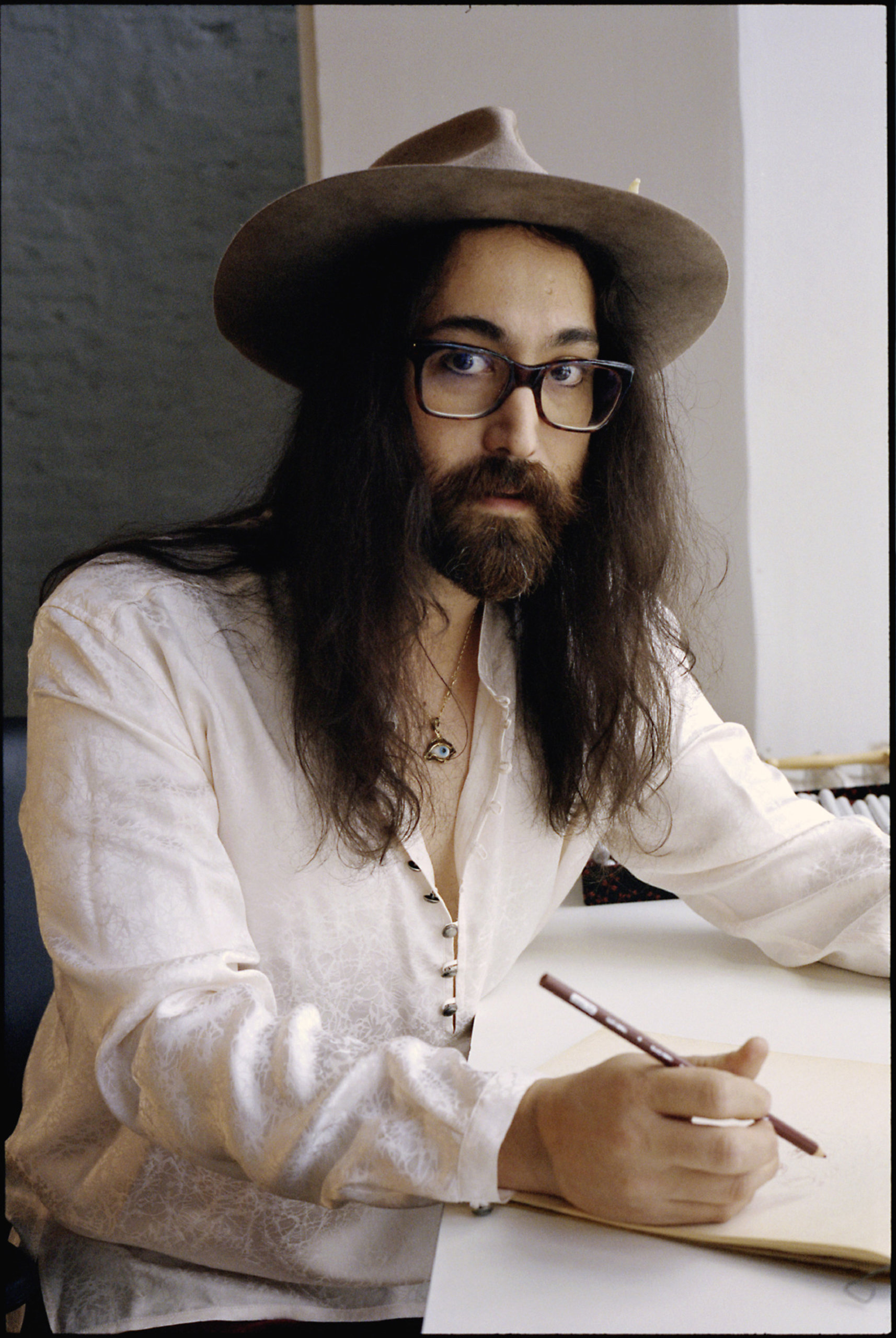

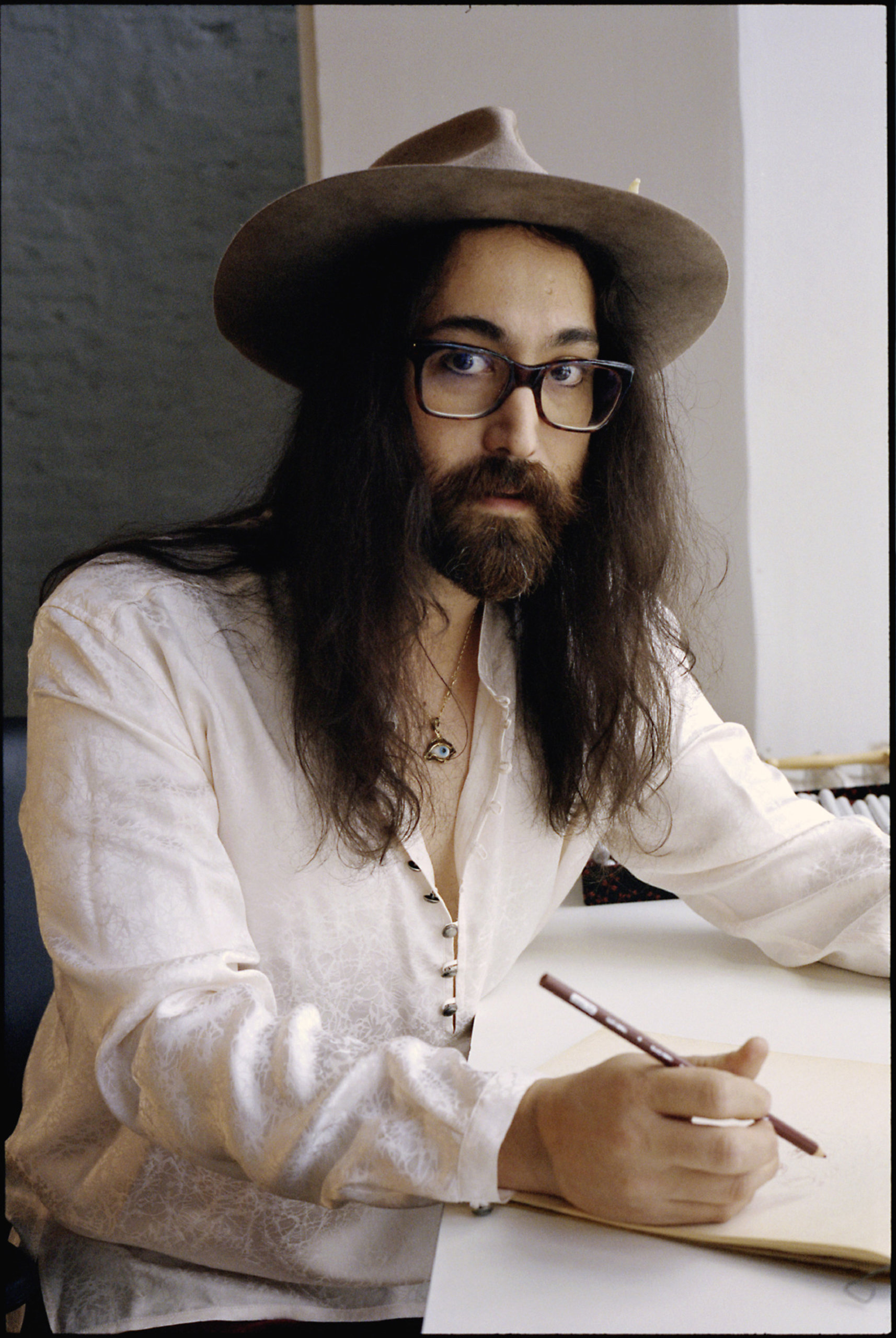

Sean Ono Lennon: Bringing The Beauty

Some stories are more personal than others.

It would be disingenuous to start this article without full disclosure — the Lennons were our neighbors at the Dakota in New York City. John and Yoko, and their young son, Sean, were frequent visitors to the 22-room apartment, facing the park, that was shared by my dad, Warner LeRoy, my stepmom, Kay LeRoy, and my three half-siblings — Carolyn, Max, and Jenny. I was also a visitor, living most of the time with my stepdad and mom in another grand dame of the Upper West Side less than 10 blocks away.

John and Kay shared in common their land of origin, and both were brought up disadvantaged, having lost their mothers early. They bonded, and would chat for hours.

Still, it was always kind of a trip to come over and see John Lennon sitting at your kitchen table, shooting the breeze. Yoko Ono was like an aunt — the aunt who would tell you to straighten your posture and to be careful about getting wrinkles (when I was 12). She would also lend a kind and compassionate ear, and thoughtful advice, when necessary.

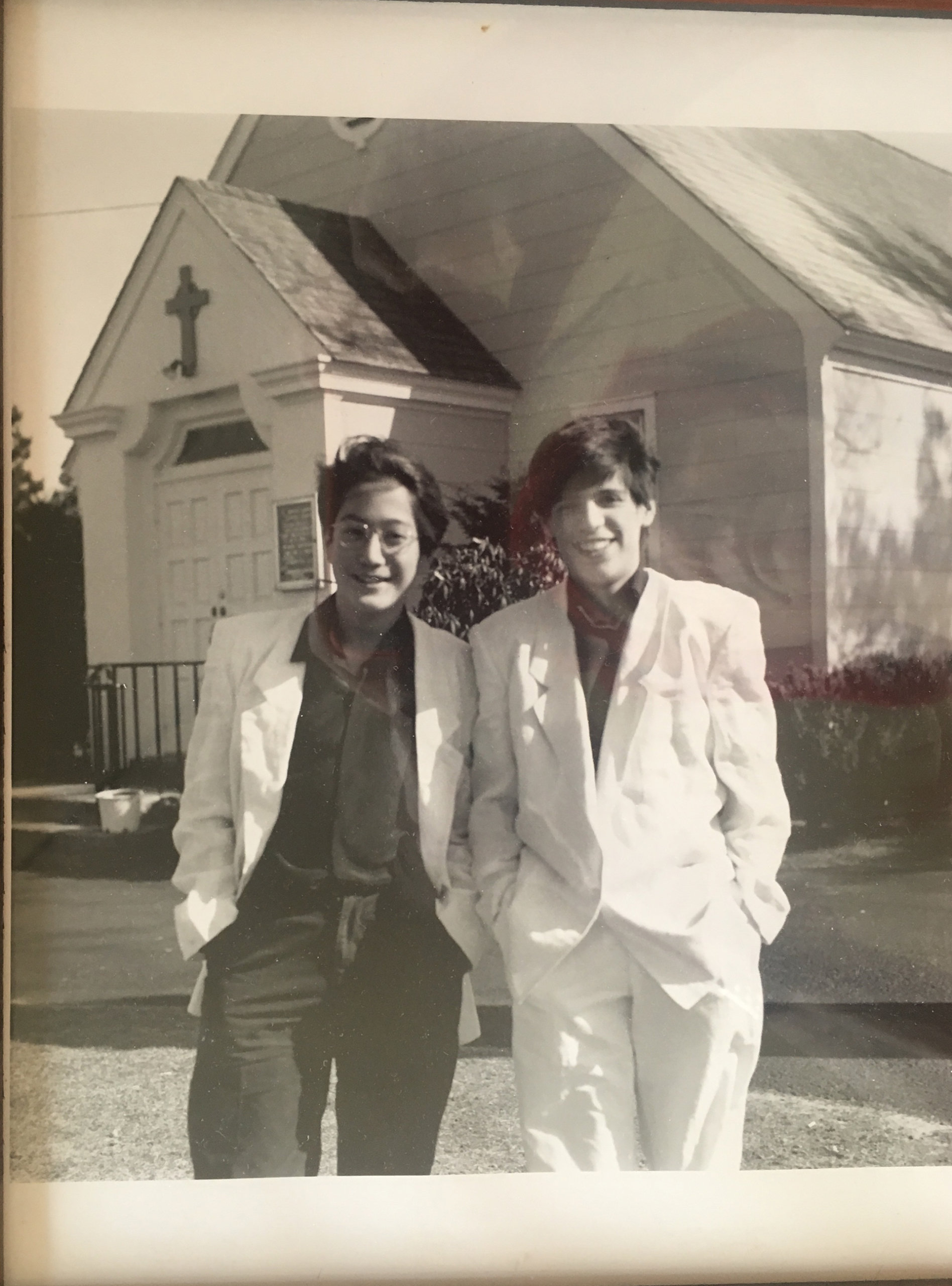

But it was Max and Sean, both before and way, way after Lennon’s assassination, who were inseparable. Almost from birth, the two did everything together. You can hear them laughing together at the end of the song “Beautiful Boy” on the “Double Fantasy” album, the last released by John and Yoko before Lennon’s death. They played in a band together, went on trips together, and spent close on three decades speaking to each other almost daily.

When my brother was killed in a motorcycle accident in 2005 at the age of 30, Sean spoke at the memorial, while Yoko clasped my hand and sobbed through the entire service. Sean and Max were not on speaking terms at that time (if you want to know why, you can use the Google), but Lennon was able to channel his frustrations and sorrow into an album, “Friendly Fire,” released in 2006, which was dedicated to Max LeRoy.

Since then, unintentionally, because of geography and general busy-ness, the visits with Yoko and Sean have become less and less frequent. So, to catch up with Sean Lennon — a dazzling musician and songwriter in his own right — was both profound and gratifying, and long overdue.

For a moment, it was like having my brother back.

We spoke about Lennon’s latest release — his third with Les Claypool — “South of Reality” by the Claypool Lennon Delirium, which is currently on tour. One can’t help but hear a bit of the Beatles in there, along with heavy doses of Yes, Pink Floyd, and utter originality.

How do you and Les play off each other’s strengths and weaknesses? And how does your writing process work?

I think the Delirium is very much a case of good chemistry when it comes to our writing process. Les has worked with many of the best musicians in the world, so when it comes to technical skills, I simply can’t compete or offer him anything useful. Instead I think my emphasis on harmony and chordal complexity is where I can contribute.

He is obviously one of the greatest players on his instrument [bass], so instead of trying to keep up with him athletically, I try and offer a different chordal context and perspective that may not have occurred to him. Les says he brings the balls and I bring the beauty, and I don’t think that’s far from the truth.

It sounds like something different is going on with the drums and bass on a few songs. Like they’re off beat, but on purpose. What creates that dynamic sound?

It could be because I’m not a real drummer. Again, Les is used to playing with some of the greatest drummers, so I think, for him, letting me play the drums was a kind of novelty, something that let him get creative in a different space. But yes, we do like odd time signatures — 5/8 over 4/4 for example.

What other bands influence your sound?

That’s a very long list indeed. For this specific band, it started with Les and I exchanging playlists of rare psychedelic and garage bands. Before we wrote any songs together, we started by playing each other rare music we were into. Examples are Dukes of Stratosphere, White Noise, July, United States Of America, The Smoke. If you want to hear some of my favorites, you can go to Sean Ono Lennon Spotify public playlists.

What’s the story behind “Blood & Rockets”? It sounds a lot like a Beatles tune.

Well, the Beatles thing is kind of in me. It’s harder to suppress than let out. The story for that tune comes from a Jack Parsons biography, “Sex and Rockets.” I often look to real life for Delirium material. I find it’s fun to play off of the surrealist expectations that accompany being a psych or prog band (whatever that means), by using the real world for narrative inspiration. [Jack Parsons was a rocket engineer, founder of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, an occultist in the style of Alistair Crowley, and, by all accounts, a super weird dude.]

What do you want your music to reflect? What’s the message, if there is one?

Honestly, I’m not together enough to have such a grand plan. I’m just happy if it doesn’t suck.

What makes you want to tour? What makes you want to keep creating? What pushes you forward?

Hmmm. I’m literally sitting at the airport after finishing a month tour, so it’s hard for me to imagine at this moment why I’d ever want to do this. But the truth is, as a musician, you’re either recording in a studio or playing live — those are the two main modes. When you’re in the studio too long, you miss playing live, and at a moment like this after a grueling tour, you miss the studio.

Nothing compares to the response of a real live audience. There is something electric about the interaction you just can’t get by yourself.

Do you have patience for nostalgic questions? Is there an insensitivity, albeit unintentional, that comes with questions about your childhood?

I don’t have any rules about what kinds of questions I like or dislike. The context and the framing, regarding who is asking and why, have more impact than the content of the question.

Yoko is still known as one of the fringe players of the ’60s, a real harbinger for the punk movement. How does she influence your music, being such an avant-garde?

She has influenced me more than anyone, even more than my father. As much as I grew up immersed in Beatles music, my dad was mostly absent, whereas I personally witnessed the recording of dozens of Yoko albums. She taught me about eq, reverb, compression. Almost all the practical things I know about professional recording I learned from my mom.

What do you like to do when you’re not making music to keep you sane?

Well, I never really stop making music. There are moments when I feel stuck so that’s when I make sure to “fill the well.” Go for walks, read great books, watch movies, eventually you’ll be inspired again.

To keep sane, I recommend meditation, exercise, and eating healthily — nothing you haven’t heard of.

Music, and marketing it, has changed so much. What does touring mean in 2019? What’s your favorite method of distribution and getting your music heard?

Well, the majority of working musicians used to make most of their earnings from record sales. Those days are over, so the result is many musicians who had retired are now out there on the road again trying to get their kids through college. The upside is you can now see Crimson and Yes and Rush on the road again. It’s likely they wouldn’t have toured without that industry sea change.

The downside is corporations are now keeping 99.99 percent of the revenue generated by songwriters. It used to be like 80 percent, and we thought that was unfair. If only we had known then what we know now, we might have adapted more reasonably to the streaming model.

I’m worried that people are losing the ability to listen to each other carefully. Could be the fault of social media, but it’s a big problem.

How has your songwriting evolved?

I think I’m getting better at songwriting. Like anything, it takes practice. The people who tend to get worse are people who become jaded by too much success. I’m lucky to have never had the kind of success that could derail my progress.

“Friendly Fire” was an album that was almost like a diary. It’s strange, but I never really look back musically, so in a sense, those songs are like photographs: they sit in a drawer somewhere but I rarely look at them.

I miss Max every single day though. No song could ever capture the love we had for each other.

What’s a question no one has ever asked you but that you want to be asked?

Honestly, I think I’ve been asked pretty much anything you could think of. Perhaps, “Hey, how about we skip the interview and go the Star Trek convention?”

What’s a fond memory of the Hamptons?

I grew up sharing summers between my parents’ house in Cold Spring Harbor, and the LeRoys’ house in the Hamptons. I was visiting some friends recently (I won’t say who), but I hadn’t realized I’d be driving through Amagansett.

It was a real shock, passing the windmill, and then the railroad tracks where Max and I used to place pennies to be squashed. I was flooded with memories, so many there isn’t the time or space to recall them here. Do you know when Proust eats the madeleine, and it summons a lifetime of memories? I’d say driving by the windmill was like that for me.

It’s strange that when you really lose things, lose them forever, is the only time you truly understand them, truly appreciate them. It’s one of life’s most painful paradoxes.

For more information about upcoming tour dates (the band is consistently playing to sell-out crowds) and to have a listen of some of the more recent stuff, visit www.theclaypoollennondelirium.com.

bridget@indyeastend.com