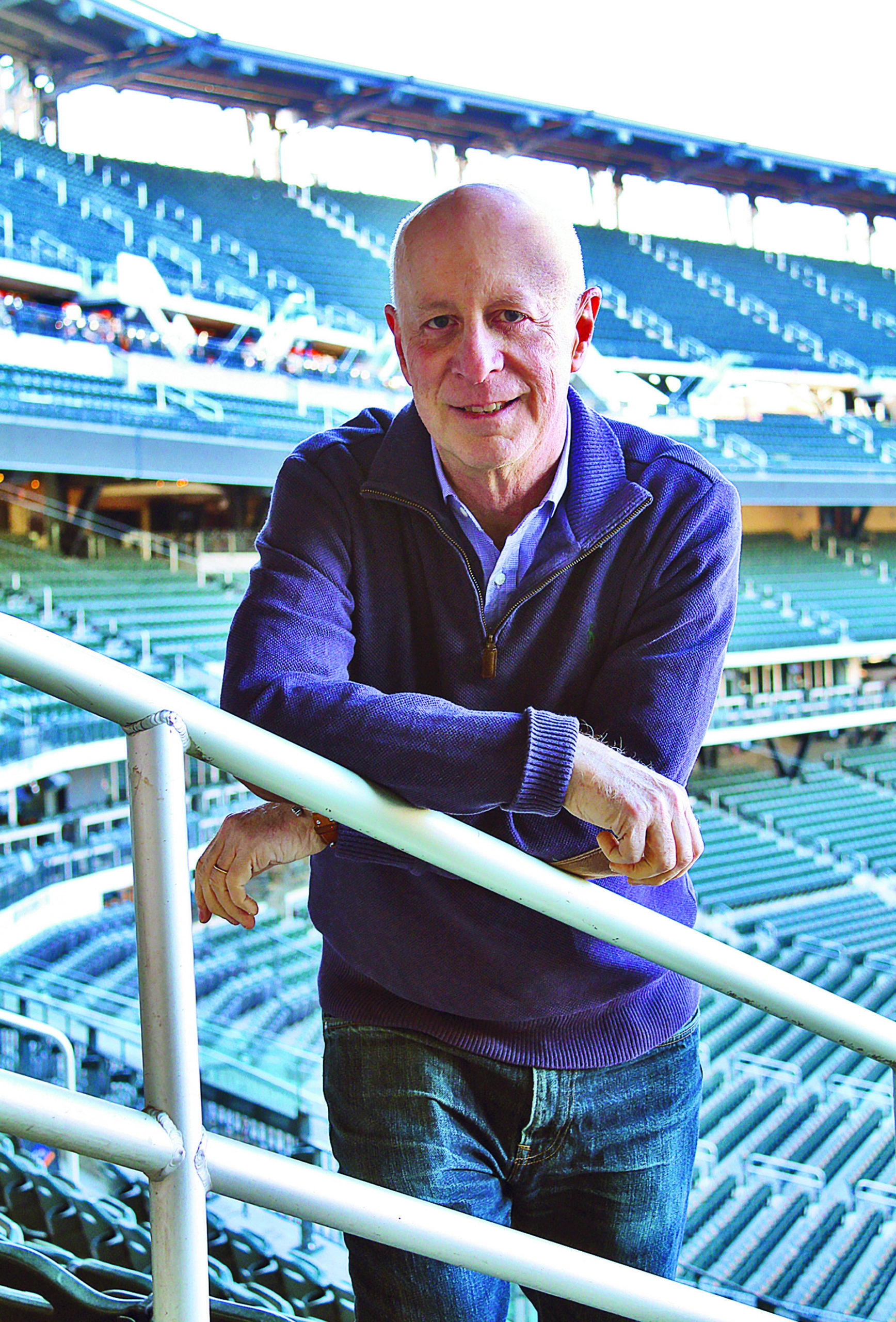

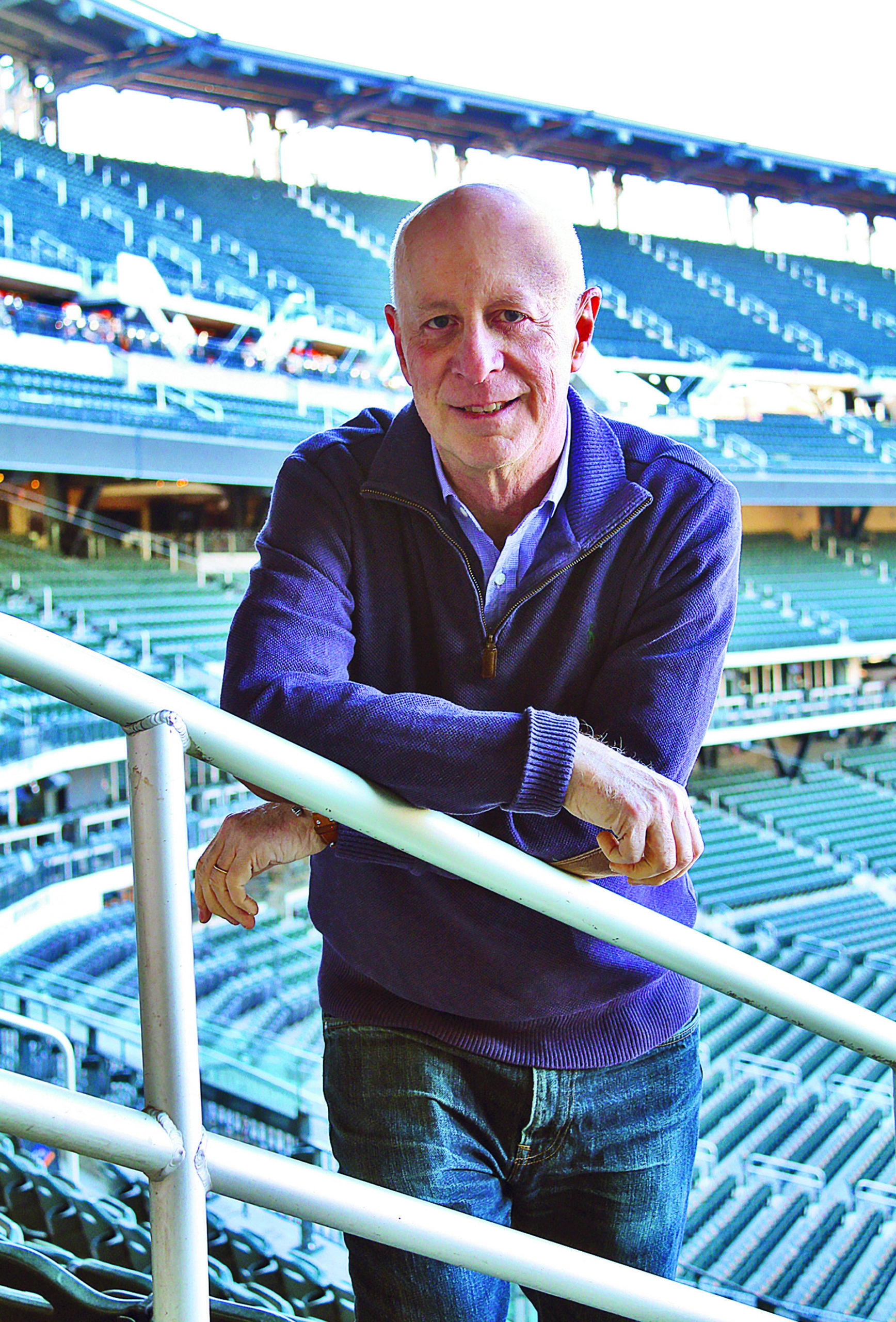

Paul Goldberger Up At Bat On Ballparks

If, as the great American philosopher Morris Cohen opined, baseball is a religion, then surely America’s ballparks are the temples where the masses can gather to share the communal experiences of hope, joy, loss, and even salvation. To watch thousands of stadium-goers leap to their feet as one, whether it’s for a grand slam or a bum call, is to see an astonishing number of people of all ilks united for a common cause, if only for a nanosecond.

But how to capture that magnificent moment when one first glimpses the outrageous, impossible green of the baseball diamond, when one emerges from a tunnel of dark alleys and asphalt urbanism into an area so colossal and all-encompassing that it is indescribable unless you’ve actually been there? Paul Goldberger, Pulitzer Prize winning author and architectural critic, has shed some light on the subject with his latest book, “Ballpark: Baseball in the American City,” a look not only at the game and the stadiums at which it is played, but at the psychological, sociological, and economic effect on the cities that are lucky enough to have their own team and arena.

“I felt like doing something different,” he said. Goldberger’s book before this one, a biography of the architect Frank Gehry, was also a departure from his other publications, mostly essays or histories, sometimes with a concentration on a particular modern master like Charles Gwathmey or Richard Meier, but without as much biographical material. “I had never written a biography before,” he said. “So even though it was architecture, it was different.”

Goldberger, a contributing editor at Vanity Fair, began his career at The New York Times, where he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism for his writing on architecture. For 15 years, he was architecture critic for The New Yorker. He has authored many books, teaches at the New School, and lectures widely around the country on architecture, design, historic preservation, and cities.

From Buildings To Ballparks

What led the East Hampton resident to switch up his focus from buildings to ballparks? Admittedly, heading into the world of sports — rife with emotional territoriality — was new turf, “but I have been a baseball fan my whole life. I cannot tell you who played in the 1927 World Series, but I’ve always loved the sport.” [By the way, it was one of the most important World Series of the early years of the sport, as the Yanks swept the Pirates, making it the first time an American League team had taken the title, as chronicled in the book, “One Summer: America, 1927” by Bill Bryson.]

“But what I can tell you,” Goldberger continued, “is that Fenway Park and Tiger Stadium, in Detroit, both opened on exactly the same day — April 20, 1912. I’ve always loved ballparks,” he said.

He recalled his first trip to a ball game, which was at the old Yankee Stadium. “I was a little kid, and I grew up in the suburbs, so I was used to lawns, but I had never seen a lawn as perfect as this, and the fact that you came to it by going through the city, and through this very urban structure, into this Garden of Eden — that’s what really got to me. Even as a kid, I couldn’t articulate it, but I felt this combination of city and country bumping up against each other in this amazing way that it does in no other place. And that is the magic of a ballpark.”

The baseball stadiums also hold a treasured past. “It really is the history of American cities,” Goldberger said. “So, this book is partly a history of baseball, but it’s also about how baseball and American cities have intertwined histories. A ballpark becomes a critical definer of urban identity, if you have a team.”

A case in point: Goldberger’s mother “was an impassioned Dodgers fan,” he recalled with a smile, speaking of the Brooklyn Dodgers, who picked up and moved cross-country to Los Angeles in 1957. “And when they left, she felt so betrayed, she not only didn’t transfer her allegiance to any other team, she simply gave up on baseball altogether. She was finished with the entire sport.”

Demolition And Restoration

As far as some of the best and worst of the past, Goldberger mourns the Brooklyn ballpark first. “Ebbets Field was the saddest loss, because it was the wonderful ballpark, it had architectural history. Since it opened in 1913, and one of the first ballparks that was a serious work of design. It had incredible baseball history. The Dodgers were such an amazing team. But it also represented the apotheosis of baseball. Never mind Cooperstown, they should have put the Hall of Fame in Brooklyn, because there is so much history there.”

Jackie Robinson first fielded second base at Ebbets in 1947, breaking the race barrier. “So, it was also a monument to civil rights,” Goldberger said. There is a plaque on the side of the housing project that now occupies the site of Ebbets Field, but the stadium was demolished in 1960. “Today I think we would not allow that to happen,” he said. “We have a much stronger sense of historic preservation.”

Tiger Stadium in Detroit is another loss. “It was not as beautiful as Ebbets Field or Shibe Park in Philadelphia, which was one of the most ornate early ones from 1909, but it had a lot of history.” There was a dark period in the late ’60s and early ’70s when the aging parks were demolished and “concrete doughnuts” were put up in their stead.

But in baseball architecture, as in the sport itself, there’s always hope. Goldberger pointed to the “positive restoration” of Fenway Park in Boston and Wrigley Field in Chicago as good examples of “how an old baseball park can be brought up to date. They are the only survivors, and they are deservedly beloved.”

Goldberger also gave a nod to Camden Yards, which, although it is relatively new, “is probably the single most important ballpark of our time. It killed off the concrete doughnut in one fell swoop.” Luckily, the Baltimore Orioles’ owners and management team had been fans of the old ballparks, and decided against another ugly artifice, selecting to go instead with a design reminiscent of the stadiums of their childhoods. “That changed everything,” Goldberger noted. Camden Yards was a phenomenal hit, and has been the touchstone for all ballparks built after it.

“There is so much specialized knowledge needed,” Goldberger said. “It’s like designing hospitals. It’s not just about the building, it’s about moving people around, and making bathrooms that work, and concessions, and parking lots,” he said. “They have improved on the design over the years too. There’s the ballpark in San Francisco on the water; that’s fabulous. It fits into the city perfectly. Pittsburgh, the PNC ballpark, is also one of the very best.”

John Thorn, the official historian for Major League Baseball said this about Goldberger’s book: “The still evolving story of the park in the city is one that Paul Goldberger tells brilliantly in ‘Ballpark,’ a book about architecture and engineering and history, certainly, but profoundly about the soul of the game and our imperiled sense of community.”

The book is available at the local book stores. Goldberger will be engaging in a conversation, followed by a book signing, with fellow author and editor Ken Auletta at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill on July 5. For more information about the event, visit www.parrishart.org. For more about Paul Goldberger’s books, you can check out his website, www.paulgoldberger.com.

bridget@indyeastend.com