Danny Peary Talks to 'How Did Lubitsch Do It?' Author Joseph McBride, Part I

You may remember that I interviewed preeminent film critic/historian and long-time friend Joseph McBride in December 2017, when he published a gargantuan anthology of his essays and interviews, Two Cheers for Hollywood: Joseph McBride on Movies. A reminder:

Danny Peary Talks To… ‘Two Cheers for Hollywood’ Author Joseph McBride

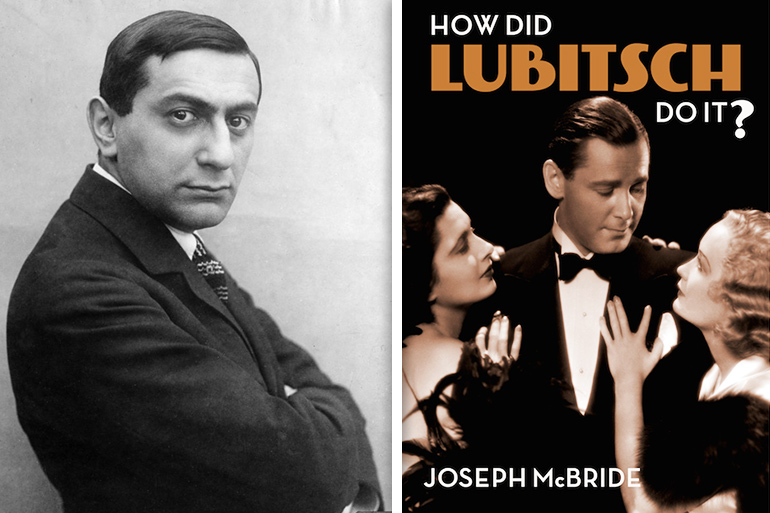

Well, despite working on other books, including the recently published Frankly: Unmasking Frank Capra, and teaching film at San Francisco State he’s back already with another humungous volume, How Did Lubitsch Do It? (Columbia University Press), a much-needed critical appraisal of one of the most important directors in cinema history, Ernst Lubitsch. McBride, who even traveled to Germany to watch the silent films he made there before coming to America, provides a brilliant shine to his fading star.

Definitely take a look at the book’s website: howdidlubitschdoit.com

This book had such appeal to me because when we both were at the University of Wisconsin in the 1960s, I was first introduced to several Lubitsch films by McBride when he ran the Wisconsin Film Society. So I was delighted that we could have the following conversation about a bigger-than-life figure who deserves such a big tribute. Here is Part I, with the concluding Part II coming next week.

Danny Peary: My sense is that you decided to write a book on Ernst Lubitsch primarily to bring him back into the public eye at a time you are frustrated by current Hollywood romantic comedies. And as an excuse to seek out his hard-to-find films.

Joseph McBride: Yes. And I felt there was an injustice in the neglect of this great artist by today’s audience. I usually write books to counteract some kind of injustice or neglect or misunderstanding of a subject of a person I care about.

DP: You wrote in the book’s introduction that you worked on it for nine years. I know how busy you’ve been, so I ask with tongue in cheek: What took you so long?

JM: Since Lubitsch was the leading director in two countries, Germany and the United States, it was a complex research topic, involving three trips to Europe to see rare Lubitsch films. And during that period I was writing several other books. I thoroughly enjoyed watching and re-watching and thinking about Lubitsch films: it’s about as much fun as you can having writing a film book

DP: You have published numerous other books in the last nine years, so I’m curious when exactly you started writing this voluminous book. Were you writing all through the years or did you wait until you finished completing your research?

JM: I waited until I had seen most of the films to begin writing. And as usual with my books, I kept researching all through the writing process.

DP: When you traveled to his native Germany to do research on Lubitsch himself and see his silent films that aren’t available here, were you open-minded about what you’d find or did you expect to fit what you came across into your already established view of him and his work?

JM: I had not seen many of his German films before I went there, so those were a revelation to me and helped enlarge my views of his life and work. As always happens, I discovered along the way what the book was about. I came to see that his films are about much more than sophisticated sexual comedy, which is the superficial view of his work, although one of the great pleasures they offer. I came to understand how Lubitsch’s films on a deeper level are about how men and women should treat each other.

DP: What do you consider his “essential” German and American silent films that every Lubitsch devotee should see?

JM: If I had to give a short list to get people started or hooked on Lubitsch, I would say Trouble in Paradise, Ninotchka, The Shop Around the Corner, and To Be or Not to Be. Seeing those films would make a Lubitsch fan out of just about anybody. And from there I would recommend some of his best German films, such as The Oyster Princess and I Don’t Want to Be a Man—both of which are viewable on YouTube—and to sample one of his spectacles, Madame DuBarry. See also the masterpieces of his American silent period, The Marriage Circle, Lady Windermere’s Fan and The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg. But there is so much more to explore, some of it hard to see, and I lay it all out in my book.

DP: In trying to give us readers a complete picture of Lubitsch, were you frustrated that 21 of the 69 films he directed are entirely missing, and others are available only in fragments? Do you think that your assessment of him would change if you got to see, rather than just read about, those films?

But I think enough of his work survives—and a wide range of films in periods and modes—that we can have a clear view of his overall evolution. One reason I wrote my book was that there was no full-scale critical study in any language devoted to his entire body of work in both Germany and the United States. There had been good books on his films in one country or the other, and there is a German collection of reviews and commentaries on his entire body of work, but I don’t think you can comprehend the entirety of his achievement without studying in detail how he developed in both countries.

While it’s tragic that so much of film history is lost, the good news is that some previously lost titles periodically are rediscovered. The only extant Lubitsch film I have not seen was just brought to light last year, part of his 1918 detective spoof Der Fall Rosentopf/The Rosentopf Case, which he stars in and directed. And the Museum of Modern Art has brought back to life his early American silents Rosita and Forbidden Paradise, which previously could be seen only in terrible dupe prints saved in foreign archives but now look beautiful again. Forbidden Paradise, however, is only 90% complete, and the pictorial quality is not as splendid as that of the Rosita restoration. These are some of the problems and limitations of film history, but for so long so much of Lubitsch has remained hard to see that I thought I would do a service by writing about it and helping create more demand to retrieve and distribute his entire body of work.

DP: My guess is that your title was inspired by the 1999 documentary, Billy, How Did You Do It?, by Volker Schlöndorff and Gisela Grischow, which is about Lubitsch disciple and collaborator Billy Wilder. But I think the title sells your work short, because you also tell us in great detail who he was, what he did, where he was when he did it, why he did it, and who he did it with.

JM: My title actually was inspired by a sign in Wilder’s office reading “How Would Lubitsch Do It?” That in turn inspired the title of the documentary about Wilder. Wilder said in 1989, “I made that sign. That way I never allow myself to write one sentence that I would be ashamed to show to my great friend, Ernst Lubitsch.” I wanted to focus people’s attention on Lubitsch’s creative process and style—how he did it—since it’s a critical study, not a biography, but in so doing I also include a lot of information and background about his life and his working methods on the set.

One of the most valuable research finds was a wealth of Paramount press releases in the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, in which Lubitsch was interviewed in detail about how he worked. He was quite precise and eloquent and witty and expansive about the subject. That was an untapped resource. I also tracked down many long-forgotten interviews with him and articles he wrote in Germany and the United States. So my book offers some fresh glimpses into Lubitsch’s view of himself, while giving my own perspective throughout.

DP: If Herman Weinberg hadn’t called his 1968 book The Lubitsch Touch, I’m sure others who later wrote Lubitsch studies would have felt obligated to use that title. Were you pleased to have the freedom to choose the title you used?

JM: Yes, I like my title with its emphasis on process—and its double entendre. “The Lubitsch Touch” is something of a reductive cliché, a marketing tool used in Lubitsch’s lifetime to promote his work, so it tends to limit his work, as does calling Alfred Hitchcock “The Master of Suspense.” (I battled the director of a documentary I wrote on Vertigo over using that phrase and lost.) But I rather like the phrase “The Lubitsch Touch” anyway because it has connotations of delicacy and sensuality, which are key to his work.

DP: When I promoted my Cult Movies books in the 1980s, every interviewer began by asking me to define “cult movies,” as a way for me to justify the inclusion of certain titles, but I felt it took away time to discuss the films themselves. Besides, my definition was personal, making it no more valid or definitive than anyone else’s. Is it the same for you when you are asked every interview to take time to define “The Lubitsch Touch”? I must say that my own definition changes by the day—today I’m thinking it is: style mixed with attitude and instinct.

JM: I don’t find it distracting in the case of Lubitsch, because attempting to define his style is the best way to analyze it. But I think people are overly fixated on “touches,” when I believe an entire Lubitsch film is a “touch.” That is the best way to look at them, particularly at the later films, in which, partly because of tightened censorship and partly because he had taken his style as far as it could go with Trouble in Paradise (1932), his way of shooting and editing became more “invisible” in the classical Hollywood vein.

Those later films are more focused on people and what they say to each other, and the camerawork, while less spectacular, is increasingly subtle. I realized in my research that it is limiting to use the phrase “The Lubitsch Touch” too much because each film, in its totality, partakes of his style and the worldview it expresses; Lubitsch scholarship and criticism is not a matter of isolating “touches” and discussing them apart from the stories and characters, as too often had been done. I wanted to offer a fully integrated study of Lubitsch as an artist in all his facets.

DP: When you watched Lubitsch’s German silent films, were you thinking they were directed by a young version of the Lubitsch you knew from his American films? Or were they already the works of a mature, sophisticated filmmaker?

JM: He grew a lot between 1914 and 1919. His earliest films as a director are rough-and-ready visually, with a lot of energy but some clumsiness and a not entirely sure-handed control of levels of comedy and how to mix them with drama. With The Oyster Princess in 1919, he became a master; he said that was the film in which he discovered his style. I Don’t Want to be a Man (from 1918) is delightful but not on that level of stylistic achievement or narrative sophistication. Before 1919 his work is promising apprentice work in both the comedy and spectacle formats.

DP: He was a tremendously successful filmmaker in Germany. You wrote that his historic spectacles even surpassed D. W. Griffith’s.

JM: I like his German comedies better than the spectacles, which seem rather ponderous today and sometimes heavy-handed, although Madame DuBarry, with its lighter approach, holds up better than Anna Boleyn and The Wife of Pharaoh. Those two are visually elegant and sometimes moving but tend to lack the humor and character nuances he brings to his best work. So while I think The Oyster Princess and other comedies from that period are splendid—The Doll is one of the most ingenious cinematic fantasies ever made, I Don’t Want to Be a Man is a sophisticated gender-bending satire way ahead of its time, and Kohlhiesel’s Daughters (which was never released in the U.S. but is viewable on YouTube) is a delightfully lusty Bavarian sex farce with a wonderful dual performance by Henny Porten—Lubitsch could be considered to have been a great director by that time, but he fully flowered in America.

He came here in 1922 and by 1924 made his first American masterpiece, The Marriage Circle, a romantic comedy that is his most influential film. It helped invent that genre and pointed the way for many other important directors to follow, from Hitchcock and Sirk and Ophüls, to Ozu and Renoir and Michael Powell. Renoir said of Lubitsch, “He invented the modern Hollywood,” and Orson Welles declared that Lubitsch “is a giant…Lubitsch’s talent and originality are stupefying.”

DP: If his career ended before he came to America, but we could see all his German films, what do you think his place in the history of cinema would be? Or if he had never made a sound film in America?

JM: We have no way of knowing how he would be viewed today if we could see all his German films, but if he hadn’t come to America but died or quit in 1922, he would probably be regarded as a quirky director who had recently flowered but defied easy definition.

He would not be considered as significant as he is today—despite the quality of his best German films—but that would be partly myopic, as is the neglect of some other important silent directors, especially those from outside the United States. Still, as great as Lubitsch’s best silent work was, sound completed him by giving him the fullest box of tools, including dialogue and music, which are so critical and delightful in his films, helping give them even greater emotional depth and further levels of stylistic play and subtlety. His mature style is evident from the start of the sound era. The Love Parade revolutionized the musical, a nascent genre, in 1929, although as the French critic Jean Douchet told me, Lubitsch already had “invented the musical” with the uproarious “foxtrot epidemic” number in his 1919 “silent” film The Oyster Princess—as we should remember, silent films were never silent but always accompanied by piano, organ, or orchestra.

DP: How well known was Lubitsch to the general public during his career, in Germany and the United States?

JM: He was regarded as the leading director in both countries, which, as Kristin Thompson observes in her book Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (2005), is a unique achievement. He became a household word in the 1930s in the U.S. and was well-known to discerning filmgoers and readers of film reviews from the time he started working here in the early 20s.

DP: In your book, you remind us that filmmakers made movies that they thought would play briefly and disappear forever. So what do you think Lubitsch’s mindset was? I’m not sure how but I think it plays into a reason he adapted so many plays into films rather than make originals—am I wrong?

JM: It was Frank Capra who told me they regarded movies as being like newspapers—they were thrown on your front page, read, and then discarded quickly. Although some films were revived from time to time, the general mindset was that film was an ephemeral medium. And in fact it always has been. Most silent films are lost. And most “films” made digitally today will be lost, though few people realize that. When Jaws was last restored, Steven Spielberg insisted it be preserved on film because celluloid, properly stored and cared for, can last a long time. But as Hitchcock once put it, “In a hundred years it’ll all be cornflakes in a can.”

DP: Lubitsch was so famous that Mary Pickford brought him to America in 1922 to direct her in Rosita. Do you think Lubitsch was sending signals or even letters to people in Hollywood indicating that he wanted to leave Germany? Could he have sought out Pickford?

JM: Some of the last films Lubitsch made in Germany were coproductions with Famous Players-Lasky, the parent company of Paramount. Hollywood had begun taking notice of him after the Great War, since his spectacles were so grand and rivaled the ones Hollywood was making. Madame DuBarry helped break the taboo on showing German films in America after the war. And as Hollywood always does, they wanted to raid a foreign film industry of its talent. German films helped revolutionize the cinema in the 20s. F. W. Murnau was also imported to Hollywood then, although he had struggles with the industry after he made the great Sunrise in 1927, and he died prematurely in 1931. Fritz Lang and many others came after the rise to power of Hitler in 1933, and like Lubitsch, Lang and some of the others had long careers in America. Wilder, with his dark sense of humor, joked later that Lubitsch was “one of the talented ones” called to Hollywood rather than having to flee Hitler, as he himself had.

DP: What is Lubitsch’s reputation today in Germany?

JM: They hold him in high regard. Several books have been published in German on Lubitsch, and his films are shown in retrospectives and other tributes. He is well-known to German cinephiles, as he is in France, even more so, I would say, than he is in the United States.

DP: I always assumed Lubitsch was being hailed by most everyone, but you point out that there has been significant criticism dating back to his beginnings in Germany. Were there critics who never appreciated him even in hindsight?

JM: Some of the leftist critics in Germany during the silent years thought he was insufficiently focused on the social causes of revolution in his spectacles and focused too much on sexual issues and other personal problems. There is some truth to that description, but it was his way of approaching human nature. Jean Renoir’s La Marseillaise (1937) is the best historical film I have seen; it starts with an episode of local injustice in the countryside and gradually widens its focus to take in all of France as the people mass to overthrow their king. Lubitsch in Madame DuBarry concentrates on the king’s affair with a common milliner and the scandal it creates over his reckless indulgence of her and the resulting injustices; the masses, personified by her young revolutionary suitor, occupy more of a subplot.

I don’t think Lubitsch’s spectacles are the equal of his comedies or some of his comedy-dramas. The spectacles were treated respectfully by reviewers in the U.S., and his subsequent Hollywood comedies often received high praise from reviewers here, even from highbrow reviewers such as Edmund Wilson and Robert E. Sherwood, but there still was a tendency among some reviewers not to fully recognize Lubitsch’s greatness because, as still happens today, comedy itself is undervalued or not taken as seriously as films with obviously momentous social content. Lubitsch’s films that do deal with political themes—such as Trouble in Paradise, Ninotchka, and To Be or Not to Be—were not recognized sufficiently in their day for the acuity of their political satire.

DP: Was he sensitive to criticism?

JM: To the extent that he lamented to his screenwriter Samson Raphaelson, “A movie—any movie, good or bad—ends up in a tin can in a warehouse; in 10 years it’s dust. You’re smart that you stick with the theater, Sam. What college teaches movies? But drama is literature. Your plays are published. Someday a student gets around to you—you have a fighting chance.” Fortunately, Lubitsch was wrong—to some extent. He still isn’t taught enough in colleges, but some of his films are shown there, and his work still lives while Raphaelson’s plays are largely forgotten. Butcinephilia is on the decline; fewer young people today care about what are called “old” movies than we did in our youth, although it’s been said that old movies are just movies you haven’t seen. When I show Lubitsch films to my students at San Francisco State University, they love them. The struggle is to get people to go to them.

DP: Do your students understand why Lubitsch’s treatment of romance and sexuality was ever considered unorthodox and controversial? And do they laugh in the right places?

JM: Students don’t laugh enough about anything, in my experience, but students to whom I show Lubitsch films find them delightful. They certainly are surprised by how sexually advanced and provocative his films are. In this neo-puritanical age, he seems all the more subversive, especially in his continental acceptance of adultery and other outré sexual practices (despite his old-fashioned acceptance of the double standard). All those aspects of his work tend to raise students’ eyebrows and generate plenty of discussion, mostly in an open-minded way, I am happy to report.

DP: In Hollywood, Lubitsch moved away from his concentration on spectacles and no longer appeared as Jewish characters in his own films, and you can probably list other changes he made. Would you say he, perhaps deliberately, reinvented himself in Hollywood or were there too many connections between his American and German films to say that?

Yes, he reinvented himself in Hollywood, quite consciously. He stopped making films with overtly Jewish characters, preferring to assimilate, like most foreign directors do, although as Joel Rosenberg notes, there are “implicit” Jewish characters in numerous Lubitsch films, including the Arab hunchback clown he plays in Sumurun (1920), his last acting performance in Germany. Overtly Jewish characters returned in Lubitsch as World War II came, such as in To Be or Not to Be and the other films with Felix Bressart, but even in those films Lubitsch was not allowed to use the word “Jew,” which was a taboo in Hollywood then except for its use in Chaplin’s The Great Dictator.

DP: Lubitsch is properly credited with inventing the Hollywood musical with The Love Parade in 1929 and other films, including The Merry Widow, because he integrated the music into the story and used non-synchronized sound so he could move the camera without worrying about noise. Why did he stop making musicals in America?

JM: Again, I think he felt he had done all he could in the genre once he had done The Merry Widow in 1934 — it’s a flamboyant visual and musical tour de force — but the changing marketplace was also a factor. That film was expensive and something of a flop. Audiences in the Depression were getting tired of musicals set in Europe or in mythical kingdoms. Proletarian comedies (such as Capra’s) were more what audiences wanted. But then the Astaire-Rogers musicals came along with their glamorous escapism, and Busby Berkeley’s musical extravaganzas also helped the audience distract itself from the Depression. But Lubitsch moved on to modern kinds of films that sometimes dealt more with how ordinary people lived, such as The Shop Around the Corner.

His career was always influenced by the world around him, even though his films were highly artificial. He returned to the musical genre only once, with That Lady in Ermine (1948), which he was directing when he died in November 1947, but it was completed clumsily by Otto Preminger, and it’s a weak imitation of Lubitsch’s earlier musical classics.

DP: You quote Lubitsch saying shortly before leaving Germany that he intended to make “modern stories about American life,” so do you think he set so few of his films in America because he thought sophisticated sexual themes worked better with European characters?

JM: Yes, that seems to have been the case. Few of his films take place in America. He found it more congenial and easier in circumventing censorship to set his films in Europe, because audiences and censors were more tolerant of the sexual shenanigans of “those naughty Europeans.” Some European critics, ironically, thought Lubitsch was pandering too much to our obsession with sexuality as a hypocritical Puritan country.

DP: You write, “Paradoxically, while subverting traditional moralism, Lubitsch made morality plays about sexuality and romance.” I do think he made films about morals, but am I wrong in thinking he didn’t really make “morality plays” because he wasn’t a moralist and never judged his characters’ suspect sexual and romantic behavior as being right or wrong?

JM: He was not a conventional moralist but he was a moralist in the Noël Coward sense of the word rather than the puritanical one: tolerant of what is usually considered human misconduct or aberration but exacting yet generous in his analysis of male-female relations. Lubitsch’s work is essentially moral in its approach in the highest sense of that often-misconstrued concept as it is defined by Coward’s Amanda in Private Lives: “Morals. What one should do and what one shouldn’t.”

DP: Lubitsch seemed to love thieves and theater people, and my guess it was because they were proficient at deceit and deception—a trait shared by most of his lead characters.

JM: Indeed. That was part of his ironic detachment from human foibles, which made him a comic artist, and part of his characteristic stance as an outsider, a byproduct of his role as a Jew in Germany with Russian roots and then as an immigrant to the United States.

DP: There are so many great characters in Lubitsch’s films but are any great individuals or even people St. Peter will wave through heaven’s gate?

JM: There are no saints in Lubitsch films, even if Satan points Henry Van Cleve “up there” after he presents himself in Hell in Heaven Can Wait. But Lubitsch loves most of his characters, and many of them are people we greatly admire for their audacity, independence, charm, and joie de vivre.

DP: Would you say that Lubitsch was braver than most of his contemporaries even after the Hays Office Code was instituted in 1934 because he, being a European, advocated adultery as a way to make marriage tolerable and made it clear that sex is a major part of romance?

JM: Certainly that is one of the most unusual aspect of his work, one that surprises audiences today. Adultery is virtually considered “un-American” in our still highly puritanical country. He somehow got away with making it mostly acceptable because of his more cosmopolitan and realistic view of marriage, although sometimes the adulterous situations in his films are painful, as in The Marriage Circle, Angel, and The Shop Around the Corner.

DP: I believe one reason his films are titillating is that Lubitsch really understood the sexual appeal of his actresses. I haven’t seen his Pola Negri films, but no else better exploited the sexual appeal of Jeanette MacDonald, Miriam Hopkins, and Kay Francis. (And perhaps Norma Shearer, Greta Garbo, and Carole Lombard.)

JM: He and his writers created a great gallery of female characters. He not only loved but understood women well. You only have to look at the films to see the richness and complexity of the roles those women play, and his comments on various actresses were both sympathetic and shrewd. Photoplay writer May Allison Quirk, after conducting an insightful interview with Lubitsch about his actresses in 1933, observed, “He knows more about feminine psychology than any man I have ever met.”

DP: Lubitsch cast a few macho leading men, including Gary Cooper in Design for Living and James Stewart in The Shop Around the Corner, but equally memorable are Herbert Marshall and Emil Jannings, who were leading men for many directors at the time, Maurice Chevalier, Melvyn Douglas and Jack Benny. What was his preference for a male protagonist? And which of his characters did he think was most like him?

JM: I wouldn’t call Jimmy Stewart macho; even in his Anthony Mann Westerns he plays a deeply vulnerable man. Lubitsch discerned the brooding, darker side of Stewart even before the actor went to war. Cooper was a devastatingly handsome fashion plate in the thirties but plays a bohemian artist convincingly against type in Design for Living. Lubitsch was not particularly interested in rough-house characters, although Jannings is hilarious in an unusual part for him as a rowdy peasant in Kohlhiesel’s Daughters. Lubitsch enjoyed the rampant skirt-chasing libido of the Chevalier character, though he also kids it and critiques it to some extent. Marshall and Douglas are the kinds of suave leading men he favors, and Jack Benny as “that great, great Polish actor” Josef Tura in To Be or Not to Be is one of the most spectacular casting coups of film history. Benny is a serious clown, as Lubitsch himself was to some extent as an actor.

DP: You write several times about the emotion in Lubitsch’s films. I recognize the emotion in your favorite of his films, Trouble in Paradise, and my favorite, To Be or Not to Be, but, for me, emotion isn’t one of the major or most distinctive traits of his films.

JM: I found more and more as I studied him that it is the emotion, as much as the comedy, that I find compelling about his work, and the way the two interrelate. His comedies are not just farcical or naughty but have deeper dimensions. I can do no better than to quote Andrew Sarris on this subject. He wrote in his landmark history The American Cinema (1968), “A poignant sadness infiltrates the director’s gayest moments, and it is this counterpoint between sadness and gaiety that represents the Lubitsch touch, and not the leering humor of closed doors.”

To purchase Joseph McBride’s How Did Lubitsch Do It?, visit this link to Amazon.com.

Danny Peary has published 25 books on film and sports, including Cult Movies,Jackie Robinson in Quotes, and his newest publication with Hana Ali, Ali on Ali: Why He Said What He Said When He Said It, about the origins of her father’s most famous quotes (Workman Publishing).