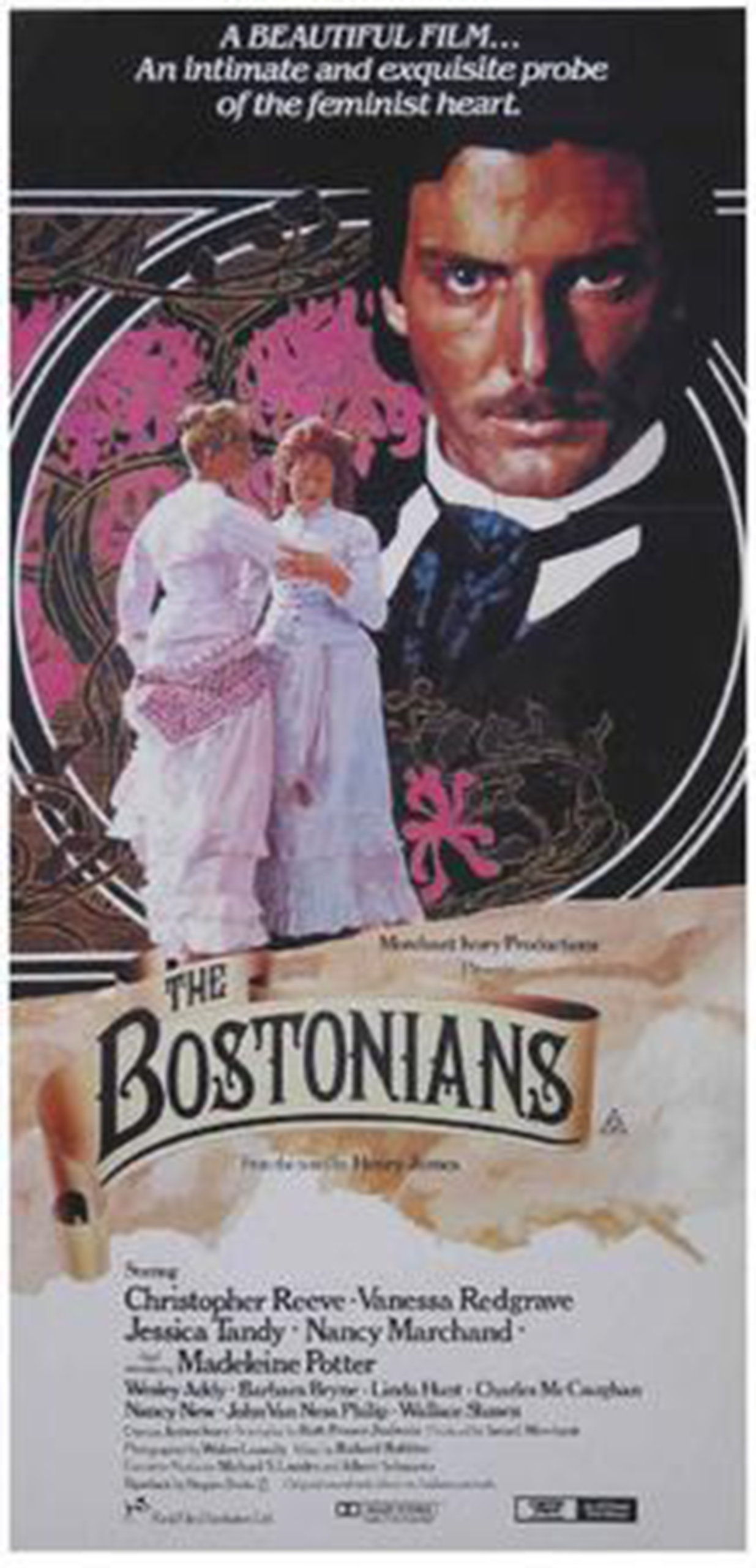

‘The Bostonians’ Delves Into Early Feminism

“The Bostonians,” like most films by the celebrated triad of director James Ivory, producer Ismail Merchant, and screenwriter Ruth Plawer Jhabvala, is intelligent, lush, and engaging — just the kind of escape into which one can thankfully sink on a summer evening. This 1984 film is a meticulous adaptation of a gripping novel by Henry James, arguably the most erudite yet accessible author of the late 19th/early 20th Century.

Seen by many as a writer of the ‘old school,’ James’s narrative techniques of shifting points of view, moral ambiguity, and authorial intervention make him a precursor of modernist literature. But it is these literary qualities, embedded in the book, that make it a challenge to translate into a satisfying cinematic work.

The story, as it unfolds, is straightforward. Verena Tarrent (Madeline Potter), a young public-speaking prodigy, is caught up in the heady world of late 19th-Century feminism, headquartered with almost messianic fervor in post-abolitionist Boston. Because of her ability to captivate audiences with improvisatory rhetoric, she is adopted as a savior of the movement by Olive Chancellor (brittle, intense Vanessa Redgrave), an introverted but fiercely determined suffragette. Their relationship becomes personal, as the naively impressionable Verena finds herself in a situation fraught with almost dangerous mentor-student power implications, underscored by an unspoken and unconsummated sexual tension between the two.

Into this hothouse atmosphere steps Basil Ransom (Christopher Reeve, denigrated by many for a previous role as Superman, but revealing a nuanced acting ability that was tragically truncated by an accident that left him paraplegic). A Mississippian stranger in a strange New England land, he is infatuated on first meeting Verena, and is drawn into an increasingly competitive rivalry with Olive. A philosophical critic of this first-wave feminism, Ransom duels with Olive using verbal weapons of increasing sarcasm, and woos Verena by casting doubt on her still-nascent allegiance to the cause.

James’s novel has a brisk and witty momentum that grows from his use of sharp dialogue, which Jhabvala’s script and Ivory’s direction draw upon and distill into a sequence of well-structured set-pieces, featuring wonderful cameos from Jessica Tandy, Linda Hunt, and Wallace Shawn. But as a visual as well as verbal artist, James also contextualizes the story with a painterly sense of place, setting the stage for Walter Lassaly’s evocative cinematography, from radiantly urban Boston to idyllic Cape Cod.

However, as the film follows Verena as she alternates between the chilly intellectual world of Olive’s militant feminists and the awakening passion of her relationship with Basil, it runs up against the quandary that all filmmakers face in adapting books. How do you translate more subtle literary concepts, crucial to the meaning of a book, into the very different language of film?

The film’s climax is a classic example of this predicament. As Verena is immobilized by indecision, on the cusp of her major address to a packed house of political supporters, she forces herself to make a life-defining choice to renounce her mentor Olive Chancellor and run away with her persistent suitor Basil Ransom.

As she abruptly leaves with Ransom, James describes Ransom’s discovery that she is in tears, and the author, adopting his sudden role as omniscient narrator, reveals the tragic implications of her impetuous decision — that in this new union she was about to enter, these tears “were not the last she was destined to shed.”

This is an unexpected revelation that pulls the rug out from the reader’s expectations, and closes the story with a jolt. But the filmmakers’ dilemma is that this crucial, dramatic, but very literary conclusion is impossible to replicate in a film script. Therefore, the film’s solution, once Verena has left, is to abruptly change focus to her rival “suitor” Olive, closing with a more traditional dramatic ending: Olive’s triumph as she replaces Verena with an unexpected oratorical performance.

This conventionally satisfying resolution is the only off note in this otherwise beautifully produced, directed, acted, and photographed film. The viewer who has not read the book will not even notice the last-minute switch in emphasis. But this is also an argument for how to approach books-into-film — to couple a close reading of the original with a comparative close viewing of the adaptation, thereby savoring the best of both worlds.

Streaming is a periodic look at classic films, available on home networks and apps. This film is currently available on iTunes and VUDU.